The second Beer Culture Summit begins Nov. 11 with “Yes…I’ve heard of you: A conversation with Dr. J Jackson-Beckham and Garrett Oliver” and concludes Nov. 14 with “Beatles, Bowie, and beer.”

Between those presentations are 30 Zoom sessions, as different from each other as the opening and closing ones. Of course, the event hosted by Chicago Brewseum is virtual. Three quick examples of what to expect:

– Nate Chapman and David Brunsma, who answered questions here last week, will discuss their book, “Beer and Racism,” and then lead a panel discussion with Alex Kidd, Ale Sharpton, Shyla Shephard and Garrett Oliver.

– Michael Roper of Hopleaf and Hagen Dost from Dovetail Brewery will demonstrate “beer poking.”

– “A motley crew of current and former beer professionals sit in front of their laptops in their respective homes and discuss the virtual beer community informally known as Beer Twitter – the good, the bad, and the borderline absurd.”

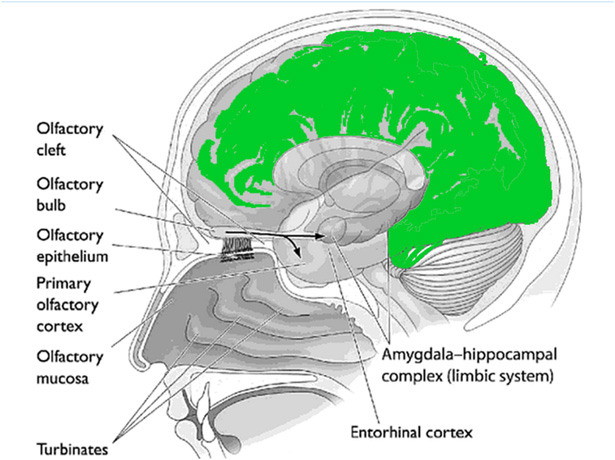

One more thing. I’ll be there on a panel talking about hops. Thus the photo at the top.

In

In