About halfway into “Craft: An Argument,” author Pete Brown cites two uncomfortable truths about craft as represented by the Arts & Crafts movement. The first is that craft is inherently selfish. The second is that it is elitist.

About halfway into “Craft: An Argument,” author Pete Brown cites two uncomfortable truths about craft as represented by the Arts & Crafts movement. The first is that craft is inherently selfish. The second is that it is elitist.

“This is why the Arts & Crafts movement ultimately collapsed over its various irreconcilable ambitions: by placing the dignity and job-satisfaction of the worker above all else and ensuring that they were paid a fair prices for their labour, Arts & Crafts objects necessarily had to sell at a higher price than mass-produced industrial products,” he writes.

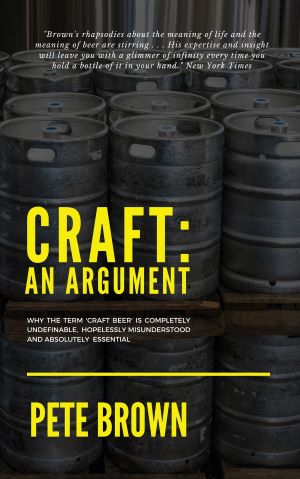

Facts are facts. Nonetheless, Brown offers a thesis that what craft beer is is revealed by examining Arts & Crafts and other similar movements. To appreciate his idea, it is necessary to move beyond the argumentsthatwillnotend about the various definitions of “craft beer” and embrace the book’s subtitle: “Why the term ‘Craft Beer’ is completely undefinable, hopelessly misunderstood and absolutely essential.”

Not surprisingly, “craft” on its own is no easier to define that “craft beer.” It is best considered as a concept, and Brown explores this across multiple eras, starting with the Arts & Crafts movement in the 19th century and including revived interest in the 1970s as well as during the recent decade. Along the way, many of the usual suspects associated with “craft beer” appear – nostalgia, independence, tradition, authenticity – warts and all.

He makes it personal, writing about the time the master cooper at Marston’s invited him to have a go at assembling a barrel as others on a tour watched. “I got as far as holding two staves against the hoop in one hand, and trying to add a third and a fourth, wondering how the hell I was going to keep them in place while I reached for a fifth, before the whole lot clattered to the workshop floor. I guess I must have tried about ten times before gently being asked to stop so we could get on with the demonstration.”

The visceral appeal of hands on resonates with him. He learned how to graft apple trees while researching “The Apple Orchard,” and spent years refining his sourdough bread skills. “The reason I make sourdough is to reconnect with physical sensations, to unify hand and head in a way I’ve rarely experienced before, bringing an end to the false Cartesian separation of body and mind. Okay, I’ll admit: I am a North London middle-class, middle-aged man, so I also make sourdough specifically so that I can post pictures of my freshly baked loves on Instagram. But destroying the false Cartesian separation of body and mind is the main reason I do it. Far more important. Honest.”

~~~~~~~~~~

Fifty-six American breweries began operating in 1988. One of them was not like the others. Anheuser-Busch spent $300 million to build its 12th plant in Fort Collins, Colo. The other 55 were considerably smaller and pushed the number of small breweries that opened after Jack McAuliffe founded New Albion Brewing in 1976 past 100.

They had much in common, and finding a word or term to use when referring to them as a group seemed like a good idea. Now there are tens of thousands of post-industrial breweries around the world and, like it or not, “craft beer” has become the default term.

As the subtitle of his book suggests, and Brown explains in the first chapters, the argument over a definition has been going on for decades. His theory is that the term “craft beer” isn’t suited for the purpose the industry has been trying to use it for. “My belief is that while it may have failed at that job, it is still useful in a much bigger way, to describe and evoke a powerful movement in the brewing and consumption of beer, and to locate beer rightfully within a broad tradition of craft, a set of ideas and approaches which help us live more meaningfully in the world.”

Not everybody will agree, or be comfortable with, some of his conclusions. “(Craft) isn’t just about the things we make; it’s about the kind of people we are,” he writes. “And for this, we get to an unspoken assumption we may be reluctant to admit even to ourselves; we believe that makers and buyers of craft products are morally superior to other people.”

This goes back to ideas put forth by the founders of the Arts & Craft movement and the belief “that the means of production affected the moral development of the workers, and that objects produced affected the moral development of the consumer.”

Does craft morality may beget craft beer morality? When Brown first announced on his blog that he would be writing this book during the coronavirus lockdown, and self publish it, he conceded he was targeting a niche. It is a niche thick with rabbit holes. They are fine places to make yourself uncomfortable and consider this question; ones about price, exclusivity and inclusivity; or other less intimidating ones.

Brown provides a way to use the term “craft beer” when discussing what drinkers understand but cannot define, and by acknowledging unpleasant truths about craft as well as celebrating what draws so many to it “Craft: An Argument” lays a foundation for richer conversations.

~~~~~~~~~~

Brown originally planned to call this book “The Meanings of Craft Beer” before Evan Rail reminded Brown of his own Kindle Single, from 2016, with the same title. Rail covers some of the same territory, although not Arts & Crafts, in a shorter book, introducing interesting evidence Brown doesn’t get to. Rail found, for instance, an additional meaning for craft in Old English that would fit quite nicely into today’s craft vs. crafty debates: “a deceitful action; a trick, a fraud.”