Brewing Industry Guide has posted something I wrote about hop terroir, available now for subscribers and later in print.

There are plenty of reasons why terroir is real, many of them science-based. That’s the core of this particular story.

There’s another aspect of the terroir conversation.

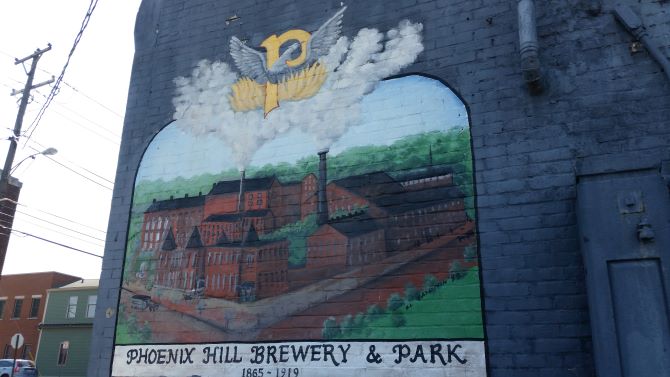

Exhibit A, from “Thirsty Work,” written by Michael Jackson for Slow magazine (the defunct magazine for the Slow Food movement) in 2002.

“Where drinks are grown, they seem a central element of life. When they are uprooted, they can lose context. It was in Britain that a combination of the Protestant work ethic and the world’s first industrial revolution created mass production, placing an ever-increasing distance between the cultivation of raw materials, the brewing of beer, and its consumption. In Britain, there is still a bruised fissure between country and town. The suddenness and brutality of the industrial revolution ripped food and drink from the soil, to the detriment of both.”

Exhibit B, from Sam Calagione’s keynote speech at the 2006 Craft Brewers Conference:

“Today wine is made all over the world but the magic and mystery of quality wine always seems to come down to place. The experts are always claiming that great wine can only be produced in exclusive places and in tiny quantities. They each preach the gospel of terroir. Holy land. Today there are almost 500 appellations, or micro-growing-regions in France alone. And there are numerous distinct terroirs within each of these appellations. It sounds confusing because it is. Divide and conquer. If you can’t blind them with science, blind them with geography. Je parl francais en peu and I’m pretty sure the translated definition of terroir is dirt. The wine world has wrapped this one word with mighty voodoo powers and created a cult of exclusivity around it.

“Breweries have terroir as well. But instead of revolving around a patch of land, ours are centered on a group of people. We operate our business on a human scale and with a human face. Today, between the constant media-blitz of advertising and marketing and the breakneck pace of production and distribution, it can be easy to overlook the passion of the person selling and that of the person buying. But it’s this shared human passion that has always fueled commerce; this opportunity to create extraordinary circumstances for the production and procurement of something new, exciting and worthwhile.”