If you have it in you to consider another 2,000-plus words on the subject, “craft brewers as authors” at Ken and Dots Allsorts provokes a few thoughts. Like with Boak & Bailey’s Ten signs of a craft brewery, Ken chooses to criteria other than size and doesn’t try to do the impossible, which would be to make quality part of the definition.

Bottom line:

I think we should understand the relationship between craft brewers and the beer they produce on the model of the relationship between authors and their works. That is, we should see craft brewers as authors. The relevant characteristic of authors for the purposes of this comparison is that authors have a large degree of control over and responsibility for the ultimate form of their work. But there’s more to it. Because the ultimate form of the work is very much their decision, they have a lot personally invested in it. An author wants to write popular books, but they want that to happen because people like the books they write rather than because they research what people already want and write something like that.

This makes it relatively easy to explain (at least to me) why a brewery can be quite large and still make beer the man or woman on the street will call craft.

In other words, what matters for craft beer is the organisational structure of the brewery. This is not a question of absolute number of employees. . . . but the more people there are, the less likely it is that anyone will stand in a properly authorial relationship to the work produced. This is why craft breweries tend to be small, because as breweries get bigger they lose that relationship. Size is a matter of organisational structure.

I like that phrase, authorial relationship to the work produced. Although my view of who contributes to the authorial process might be broader that yours. I’m inclined to give creative credit to more than just the guy who writes the recipes.

Perhaps I also find it easier to find “proper” authorial relationships (honestly, I don’t know), and thus to understand why a single tank at Sierra Nevada Brewing may contain as much beer as the average brewpub makes in a year — and the ones at New Belgium are even bigger. (Got more time? Read SF Weekly on the The Artisanal Irony: The Mass-Produced Hand-Crafted Food Dilemma.)

Six years ago, after Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head Craft Brewery invited a group of five other brewers (who Dick Cantwell of Elysian Brewing would then call the “Brett Pack”) to visit Belgium with him I sat in the middle of a roundtable discussion that ended up being a story in All About Beer Magazine. One of my questions was, “Can you still say the beers, the recipes, are your own as you become a larger brewing company?”

Rob Tod of Allagash Brewing answered, “As you business grows you have to have more good people making decisions. The problem with the big breweries is they may have great brewers but their company culture is to dumb down everything they do (to reach a broader audience).”

I want beers from a brewery where the people who work there don’t know any better, as opposed to those from a place where that know what doesn’t work.

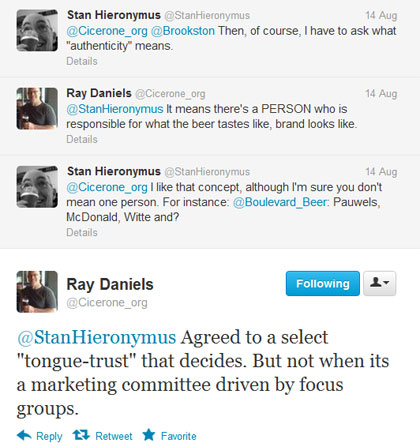

And I think all of this aligns with a conclusion Ray Daniels seems to have come to recently during a series of tweets.

Granted, there is a danger of taking this too far, of turning everybody who touches a hop into a rock star (search for “rock stars” at a Good Beer Blog to see what Alan thinks of that) because beer has become part of the “artisan” movement. Joel Stein pointed this out brilliantly (in a slap-your-knee-while-you-laugh way) a while back in Los Angeles magazine.

First, we idiotically agreed to learn every chef’s name. Then every species of fish, every variety of apple, and every type of heirloom wheat. Now farm names—even those of the specific farmer—are expected cultural knowledge, edging out any chance for poets, painters, and people who rant in magazines about food trends. What will we have to memorize next—the names of the guys who pick our fruit? “Oh, Juan Hernandez picked the strawberries in the sorbet? He’s got a very delicate hand!”

In fact, we don’t need to know the name of every brewer (sorry, Jared) who has a hand in each batch produced at [fill in the name of the brewery of your choice]. But I like knowing they are there and that they are allowed to make a difference in the beer that ends up in my glass.

Craig Gravina at

Craig Gravina at