Pete Slosberg devotes a chapter in Beer for Pete’s Sake to his brewery’s battles with Anheuser-Busch. He tells a series of amusing stories, including one pitting his dog, Millie, against Budweiser’s Spuds MacKenzie, and in each of them Pete’s Brewing Company was David. Anheuser-Busch was Goliath.

Pete Slosberg devotes a chapter in Beer for Pete’s Sake to his brewery’s battles with Anheuser-Busch. He tells a series of amusing stories, including one pitting his dog, Millie, against Budweiser’s Spuds MacKenzie, and in each of them Pete’s Brewing Company was David. Anheuser-Busch was Goliath.

In the early 1990s Pete’s was the second largest of a new wave of breweries that had outgrown the micro tag and now were described as craft. Its sales peaked at 425,000 barrels in 1996, but it was still the second largest craft brewery in 1998 when the Gambrinus Company bought it. Slosberg remained for two years and it would be another dozen before the brand eventually died. On the jacket of the book, published in 1998, he is described as “a brewing maverick, a brilliant entrepreneur, and iconoclast, and a marketing icon.” As important, he took “a path that led him from (my emphasis) a corporate career to doing what he loves.”

This was, and in many cases still is, a familiar story. Hate your job? Become a brewer. This is an example of why J. Nikol Beckham writes in a new collection of essays that “the microbrew revolution’s success can be understood in part as the result of a mystique cultivated around a group of men who were ambitious and resourceful enough to ‘get paid to play’ and to capitalize upon the productive consumption of fans/customers who enthusiastically invested in this vision.” The title of this fourth chapter in Untapped: Exploring the Cultural Dimension fo Craft Beer is a mouthful: “Entrepreneurial Leisure and the Microbrew Revolution: The Neoliberal Origins of the Craft Beer Movement.” Not surprisingly, there’s a considerable amount to define and discover en route to Beckham’s conclusion.

It is worth the time to get there, because it broadens our understanding of the culture and business of beer— where its been, where it is, where its going. In Untapped’s foreword, Ian Malcom Tyson writes, “As sociologists examine these trends, they bring insights that journalistic interpretations often gloss over. They provide nuanced answers to far-ranging questions of how seemingly commonplace products such as beer can have such a fascinating esoteric heritage.” As a journalist I am sure how I feel about that, but I appreciate reading what somebody else sees when they tilt the glass sideways.

Read more

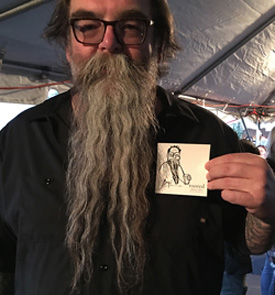

Beer writer Pete Brown was conducting a tasting of IPAs when a woman in the audience raised her hand to ask a question.

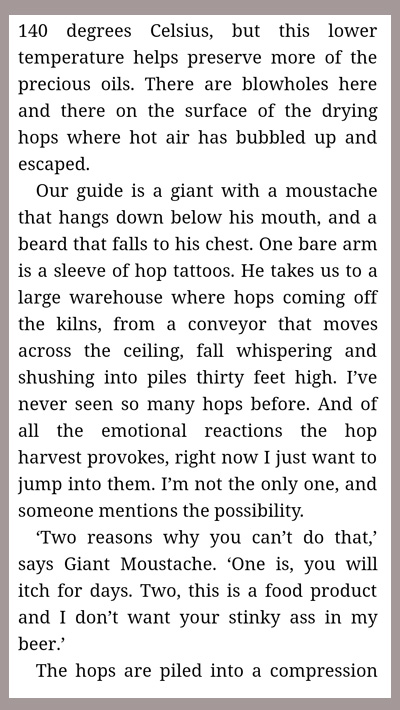

Beer writer Pete Brown was conducting a tasting of IPAs when a woman in the audience raised her hand to ask a question. I apologize, because what follows is strictly American hop industry inside stuff. But I’ve reached the hops section of

I apologize, because what follows is strictly American hop industry inside stuff. But I’ve reached the hops section of

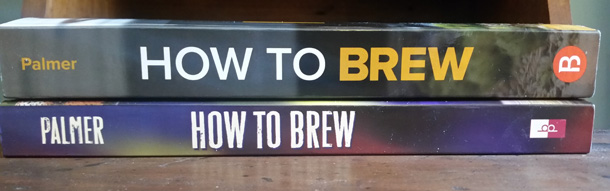

How to Brew is one of two thoroughly revised essential beer books published this spring. The mission of the other,

How to Brew is one of two thoroughly revised essential beer books published this spring. The mission of the other,