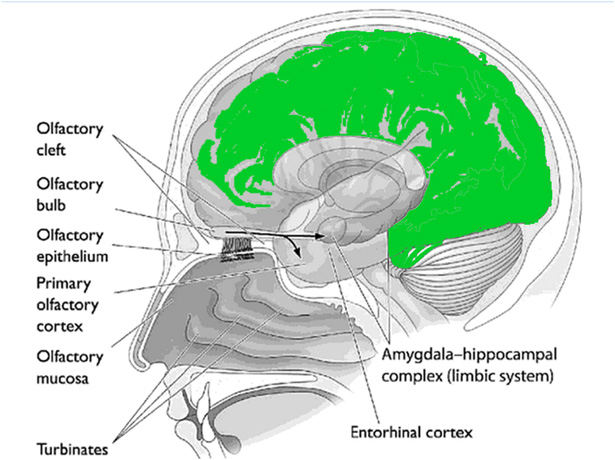

I often use this illustration when I am speaking to a group about hops and aroma. I also posted it here a few years ago. I call it “your brain on hops.”

Following up on last week’s post about Covid-19, loss of smell and catty IPAs there is this very long article from The New York Times Magazine. I don’t know how many words there are in the story, but it takes 50 minutes to listen to it.

It turns out that examining the impact of Covid-19 on aroma may help us understand both better. All the attention focused on anosmia, and parosmia, that results from Covid-19 has made more people appreciate the sense of smell. It has gone from a “bonus sense” to a dominant one.

Or as Brooke Jarvis writes: “Smell is a startling superpower. You can walk through someone’s front door and instantly know that she recently made popcorn. Drive down the street and somehow sense that the neighbors are barbecuing. Intuit, just as a side effect of breathing a bit of air, that this sweater has been worn but that one hasn’t, that it’s going to start raining soon, that the grass was trimmed a few hours back. If you weren’t used to it, it would seem like witchcraft.”

And I’ll be adapting these thoughts for my next presentation: “Genetics plus life experience, the natural attrition and regrowth of your epithelium (it may be that the more you smell an odor, the more receptors you develop that can perceive it), mean that 30 percent of your receptors may be different from those of the person next to you. Culture, too, plays a role: Whether you think lemon smells ‘clean’ or not may depend on whether you grew up associating it with cleaning products or with hot, overripe citrus groves.”

I’ve been busy with hop-related matters this week. As a consequence I’ve noticed more than one brewer listing “hand-selected hops” in their beers. “Nose-selected” sounds awfully strange, but it would be more accurate.

Looking for answers he turned to “What the Nose Knows: The Science of Scent in Everyday Life,” a book I found essential when writing about aroma in “For the Love of Hops” and one I recommend for anybody interested in unraveling the mysteries of our most complex sense.

Looking for answers he turned to “What the Nose Knows: The Science of Scent in Everyday Life,” a book I found essential when writing about aroma in “For the Love of Hops” and one I recommend for anybody interested in unraveling the mysteries of our most complex sense.