Jean-Marie Rock began brewing beer professionally in 1972. For the last 25 years he’s been in charge of the Orval Trappist monastery brewery. He understands brewing cred. Celebrity? Another matter.

He’s been to Kansas City twice recently. Posing for pictures, signing empty beer bottles, he found out quickly he wasn’t in Belgium any more.

“The biggest change is the contact brewers have here with the customers,” said Steven Pauwels, a native of Belgium who became brewmaster at Boulevard Brewing in 1999. When Rock agreed to collaborate with Pauwels to brew a beer he probably didn’t realize that 160 people would show up at a Lawrence, Kansas, hotel to celebrate the release of Smokestack Collaboration No. 1.

“The American people are so kind,” Rock said. “You cannot refuse to answer their questions.”

Rock, who is 61, oversees the production of a single beer, Orval. (The brewery also makes Petit for the monks at the monastery to drink and to sell at the brewery’s inn — that is simply a watered down version of the mother beer.) The ongoing production of special, or seasonal, beers is something that makes New American beers (I’m using that term instead of “craft” to see if it sticks) different. Likewise the notion brewers might be celebrities.

Rock, who visited Kansas City first to brew the beer and then again two weeks ago for the debut, left no doubt he found brewing something different just plain fun. When Pauwels suggested the possibility of the collaboration last year Rock knew immediately that he wanted to brew a strong pilsner using a hopping technique from 30 years ago.

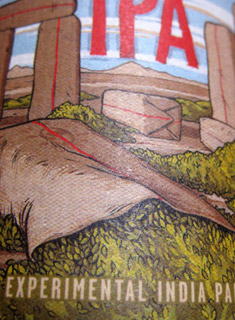

Rock first worked for the Palm Breweries, then for Lamot in Mechelen, brewing lagers. At 8 percent alcohol by volume Collaboration No. 1 is about one percent stronger than the beer Rock was thinking of. Although it is labeled an “Imperial Pilsner” is does not resemble beers such as Samuel Adams Imperial Pilsner.

Hopped with excessive quantities of German Hallertau Mittlefrüher (as it is spelled where it is grown) Boston Beer brewed an 8.8 percent abv beer that had 110 International Bitterness Units (IBU).

Collaboration No. 1 is hopped entirely with Czech Saaz and brimming with hop flavor, although with 30 bitterness units it appears almost pedestrian compared to 110 IBU.

Where does the flavor and aroma come from? First wort hopping, a practice no longer used in Belgium. “No, no, no, no, no, no,” Rock said. “It doesn’t exist any more.”

A quick primer for those who aren’t homebrewers, commercial brewers or among those who spend too much time with either. Brewers boil hops a an hour or more to extract bitterness. In the process flavor and aroma are lost. That’s why brewers make flavor and aroma additions later in the boil.

In this beer two-thirds of the hops were added before the beginning of the boil (or “first wort”), but their flavor ended up in the beer. German also brewers used the method at the beginning of the last century (you can read much more here, including results of tests conducted in 1995.)

“It seems like a contradiction. You’d think you’d get more bitterness and less flavor,” Pauwels said. “It’s more subtle, almost crisper. Sometimes with late hopping it can get vegetative.”

These days many American brewers are experimenting with first wort, and even mash, hopping (recall at the steps Deschutes took in making Hop Henge). Additionally dry hopping (adding hops after fermentation is complete, sometimes shortly before packaging) to produce even more aroma is commonplace.

“You can try all the things you want,” Rock said. “A lot of brewers they are doing all they can dream. The dream is not always the reality.”

Rock is happy with Collaboration No. 1 (“Not just because it is our beer”). “It has a taste you don’t get when you use late hopping,” he said. “You get an old taste. That is my opinion.”

You know, old like the good old days. When a brewer could go to the store to buy a loaf of bread and didn’t have to stop to sign autographs.

(Photo courtesy of Boulevard Brewing.)

Both the beer and the details herein.

Both the beer and the details herein.