The BBC Pure Hop Pellet is not exactly new. Boston Beer Company has been using this custom pellet for several years, since developing it in collaboration with the Barth Haas Group.

But that eight hop varieties will be available to other breweries in this form after the 2015 harvest is new.

Not long after Eric Beck of Boston Beer and Christina Schönberger of Barth Haas completed a presentation titled “The Evolution of a New Hop Pellet Type for More Efficient Dry Hopping” during the Craft Brewers Conference two weeks ago Matt Brynildson of Firestone Walker stopped at the Barth Haas group to say hello to Schönberger. I asked him if he’d be interested in using such pellets in his brewery.

“Sure.”

I consider than an endorsement.

Backing up, because you probably haven’t memorized “For the Love of Hops” (the custom process creating the pellets used in Samuel Adams beers is discussed on page 226). Hops are first milled in a hammer mill, preferably under refrigeration to reduce losses of alpha acids and essential oils. Hop powder is accumulated in a mixing vessel and then pelletized. These may be Type 90 pellets or Type 45.

T90s once contained 90 percent of the nonresinous components found in hop cones, thus the name, although today product losses are generally less and the percentage is actually higher. They are the most common sold. The composition of oils and alpha within the pellets is similar to cones but not necessarily identical.

T45, or lupulin-enriched, pellets, are manufactured from enriched hop powder. Processors mill the hops at about -20° F (-30º C), which reduces the stickiness of the resin, and separate the lupulin from unwanted fibrous vegetative matter. Although the name implies the hops are enriched to twice the level of T90s, the level may be restricted by the amount of lupulin in the original hop. Normally, processors customize the level, producing, for example, a T33 or a T72 pellet that would still be referred to as a T45 pellet.

BBC Pure Hop Pellets are produced on the T45 line, but with more like 90 percent of hop matter. (More like, because T90s really contain close to 95 percent, and BBC a bit less than that). The percentage is important to Boston Beer. David Grinnell, vice president of brewing, explained that when the brewery was looking for an alternative to T90s they could have decided to use Type 45 pellets. They reduce the space needed for storage and deliver more lupulin more efficiently. “Concentrated lupulin is not unattractive, but it’s not the whole hop. We’re committed to the whole hop,” he said. “Somewhere in your brain you know (that) will have value.”

Or as Beck said during the presentation, “We believe … (it) reminds you that you are drinking beer.”

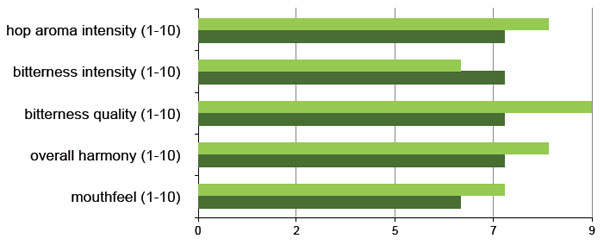

This graph shows the difference in sensory impact that Boston Beer found when using Mittelfrüh in Boston Lager (“Pure Hop” process is on the top). Of course, this will vary based on variety and type of beer being brewed. However, it should be apparent brewers can either choose to use fewer hops for the same impact or get more impact with the same amount of hops.

Barth Haas has facilities to make T45s in Germany and in Yakima, Wash. (For the record, so does Hopsteiner.) Haas will initially produce Mittelfröh, Hersbrucker and Saaz Pure Hop Pellets in Germany. For now, it will make Citra, Cascade, Centennial, Equinox, and Mosaic Pure Hop Pellets in Yakima. “We want to make sure we can serve the market,” said Alex Barth, president of John I. Haas, Barth’s U.S. company.

That means you aren’t going to see them everywhere. Haas serves mostly regional-size breweries directly, with channel partners selling to smaller ones (and the homebrew market). Larger breweries are the ones that will find the most use for the dry hop friendly pellet — they are the ones still sorting out more efficient ways to dry hop large amount of beer without clogging their filters and wrecking centrifuges. “It will take some time to filter through the market,” Barth said.

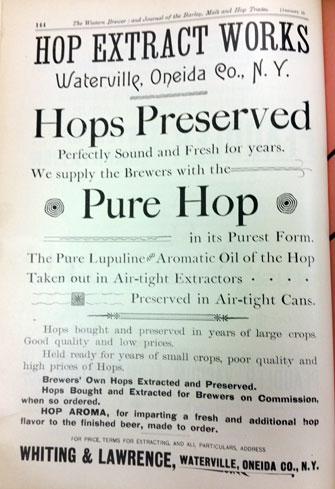

– Hop extracts are not exactly new. The New York Hop Extract Company built the first extraction plant in the world large enough to produce quantities sufficient to supply brewers in 1870. Brewers bought extract when hops were plentiful and prices low as insurance against poor crop years and high prices, using it in combination with whole hops.

– Hop extracts are not exactly new. The New York Hop Extract Company built the first extraction plant in the world large enough to produce quantities sufficient to supply brewers in 1870. Brewers bought extract when hops were plentiful and prices low as insurance against poor crop years and high prices, using it in combination with whole hops.