Which one of these has nothing to do with the amount of beer a monastery brewery makes?

a) The number of monks living at the monastery.

b) How many of the monks are priests.

c) If there is a nearby convent.

d) Whether the monastery is Benedictine or Trappist.

e) If the brewery operates a cafe that serves its beer.

Don’t spend too much time thinking about it. It is a trick question. The answer is “f) all of the above.”

But you wouldn’t know it based on this headline (and the story below it): “Fewer Monks Means Less Belgian Beer For Its Fans.”

Forbes contributor Cecilia Rodriguez writes that Orval, located in the south of Belgium, is in danger of losing its Trappist appellation because of a dwindling number of monks at the monastery.

Due to a shortage of monks … their traditional drink can’t keep up with demand — and it’s about to lose its distinctive and elusive Trappist appellation.

No, Orval is not in danger of losing the right to label its beer Trappist.

Rodriguez reports the number of monks has fallen from about 35 in the 1980s to 12 today. That’s down from 16 when I visited the abbey before writing Brew Like a Monk”. But, here’s the thing: When I visited I was told that one monk had ever been involved with any aspect of the brewing operation since it resumed in 1932, and he drove a forklift truck in the packaging hall.

The number of monks is decreasing, sometimes dramatically, in Trappist monasteries around the world, although the actual number of monasteries more than doubled between 1940 and the beginning of this century. It is something to take seriously, more seriously than beer, but totally unrelated to how much beer a monastery brewery might produce. In order for a beer to be labeled Trappist it must be brewed under the supervision of the monks, not necessarily by the monks themselves. And “supervision” does not mean overseeing day-to-day operations within the brewery. As long as there are monks living at Orval there almost surely will be Orval beer.

Here’s a chart assembled from research in 2005:

| Monastery | Production | Brew staff | Monks | Monks in br’y |

| Achel | 2,000 HL | 2 | 17 | 1 |

| Chimay | 120,000 HL | 82 | 20 | 0 |

| Orval | 45,000 HL | 32 | 16 | 0 |

| Rochefort | 18,000 HL | 15 | 17 | 6 |

| Westmalle | 120,000 HL | 41 | 20 | 0 |

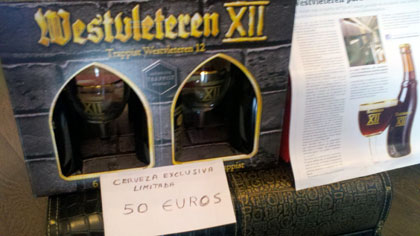

| Westvleteren | 4,750 HL | 10 | 28 | 7 |

Since then, during the same period the number of monks at Orval decreased one third, beer production rose from 45,000 hectoliters to 70,000. Output now is equivalent to a little more than 38,000 U.S. (31-gallon) barrels, or what Georgetown Brewing in Washington produced in 2012.

Coincidentally, three days after the Forbes scare story appeared Beertourism.com (which promotes beer and food in Belgium) had an interview with Anne-Françoise Pypaert, who recently took the reins from longtime Orval brewmaster Jean-Marie Rock. Pypaert began working at Orval in 1992 and has see the brewery expand and modernize several times over. She talked how space constraints limit production, but not at all about a shortage of monks in the brewery or concerns Orval will lose the right to label its beer as Trappist.

She also discussed the cheese operation, because she also inherited supervision of cheese making — 260 tons annually — from Rock. It’s dang good cheese. How come we haven’t seen a “Fewer Monks Means Less Belgian Cheese For Its Fans” headline?

Beirens appreciates the importance of commerce to the monasteries, and that the six Trappist breweries are part of a larger family. He distributes a range of monastic products — beer is the best selling, but they include cookies, soap, vegetables, wine, and other goods — throughout Belgium and France. His father did the same. “I’ve been visiting monasteries since I was this high,” he said earlier, holding his hand below his waist. That’s why he understands something else about monasteries.

Beirens appreciates the importance of commerce to the monasteries, and that the six Trappist breweries are part of a larger family. He distributes a range of monastic products — beer is the best selling, but they include cookies, soap, vegetables, wine, and other goods — throughout Belgium and France. His father did the same. “I’ve been visiting monasteries since I was this high,” he said earlier, holding his hand below his waist. That’s why he understands something else about monasteries.