Back for a second time, Samuel Adams Hallertau Imperial Pilsner remains a beautiful — if big at 8.8% abv and 110 IBU — tribute to the Hallertau Mittelfrueh hop. Or Mittlefrüher as it is spelled in the Halltetauer region of Bavaria.

Back for a second time, Samuel Adams Hallertau Imperial Pilsner remains a beautiful — if big at 8.8% abv and 110 IBU — tribute to the Hallertau Mittelfrueh hop. Or Mittlefrüher as it is spelled in the Halltetauer region of Bavaria.

Lew Bryson already provoked a long enough discussion about calling it imperial pilsner, inspiring a nice treatise on balance by Stephen Beaumont. Consider those topics dealt with.

Instead, some answers to the question “Why?” The short answer is: “Mittelfrüh (Mittelfrueh)”

“We think they are the best hop in the world,” Boston Beer founder Jim Koch said when the 2005 vintage was released. “We wanted to showcase them. It is neat you can get all those flavors from one hop variety.”

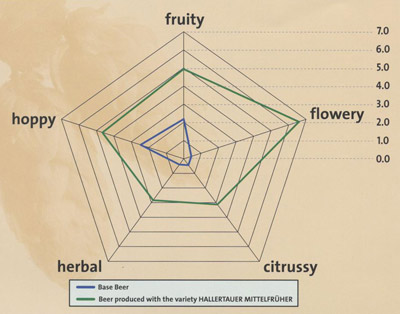

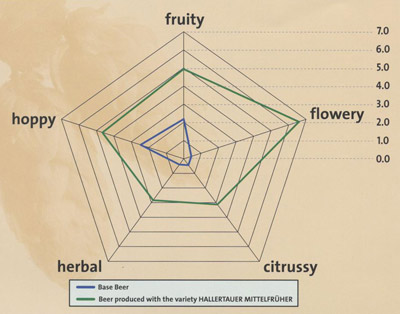

Mittelfrueh Aroma

There’s a technical aspect to this you may already know. Or not. Basically, IBU stands for International Bitterness Units and an IBU is one part per million of isohumulone. Brewers calculate how much bitterness to expect based on the alpha acid percentage of particular hops, the amount of hops used and the utilization (length of boil is most important; there are other factors and let’s stop there).

The most efficient way to add bitterness is by using high alpha hops (with AA percentages ranging from the mid to high teens) This is true even for international lagers hopped below the threshold at which you can can taste hops. What isn’t efficient is using a low alpha hop like Mittelfrueh (3-5% AA).

In fact most international lagers include about two ounces of hops per barrel (31 gallons). Boston Beer uses one pound per barrel to make Boston Lager. The brewers tossed in 12 pounds per barrel (100 times the amount in an international lager) in the Halltertau Pilsner.

“Twelve pounds,” Koch said, sounding downright giddy. “While we were doing it Dave Grinnell (one of the brewers) referred to it as a reckless amount of hops.”

The brewers created several test batches, managing to come up with beers in which the IBU topped 140. That’s measured. Most of the time when you see a small brewery cite IBU it’s calculated. As the amount of hops increase efficiency drops dramatically and those calculations aren’t particularly accurate. Few Double (Imperial) IPAs actually reach the 90s when checked with proper measuring equipment.

The calculated IBU on the batches at Boston Beer were well above 300. “We were in the range where all bets were off,” Koch said. “You have to place it under an analyzer to get an accurate measure.”

He found the version in the 140s was too bitter, so the brewers blended in a 100 IBU batch and eventually found a sweet spot in the 110-115 range.

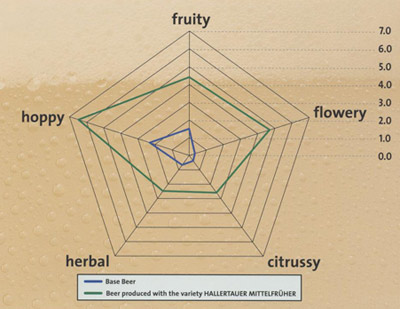

Mittelfrueh Flavor

The beer is cloudy — the brewers didn’t want to filter out the hop flavor, bless them — and doesn’t look particularly pilsner-like. The Mittelfrueh doesn’t come off as particularly delicate in this quantity — and matched against a solid one-two punch of malt and alcohol — but proves you can turn the flowery-citrussy-spicy hop flavor volume way up without the discordant impression you get from a cheap pair of speakers.

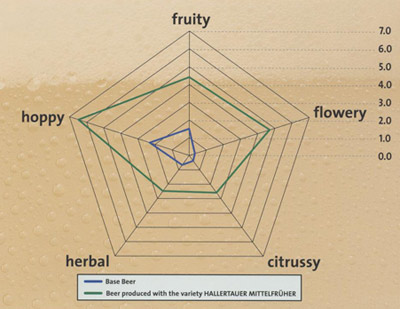

The illustrations here come from a book put together by the hop growers in Hallertau, and for it they commissioned panels to evaluate the intensity of both the aromas and flavors of their hops. Notice (above) how the hoppy/bitterness impression of Mittelfrueh changes from aroma to flavor.

“We don’t like it when the discussion about hops is focused only on alpha acids,” said Dr. Johann Pichlmaier of the Association of German Hop Growers. Once again skipping most of the geeky details, Mittelfrueh has a surplus of hop oils that help qualify it as a “noble” hop.

Koch agrees. “Hops are not primarily about IBUs. Hops are about a bounty of flavors,” he said. “With this beer your tongue is indelibly imprinted with the cornucopia of flavors you can get only from noble hops. There’s a reason brewers treasure these hops; a reason they cost more.”

First time around the brewery publicized the (crazy) bitterness units in the beer. This time there’s no mention of IBU.

That’s the right way to talk about hop flavor in general and Mittelfrueh in particular.

Ralph Olson of Hop Union discusses the 2007 hop crop. How grim is it? “The hop world is upside down. In the future we see the possibility of brewers shutting down for lack of hops.”

Ralph Olson of Hop Union discusses the 2007 hop crop. How grim is it? “The hop world is upside down. In the future we see the possibility of brewers shutting down for lack of hops.” but the book should be on the shelves soon and I’ll have a review sooner. Before you dig into that for a couple of hundred good ideas here’s one not in the book. From Saturday while camping in the Manzano Mountains:

Back for a second time, Samuel Adams Hallertau Imperial Pilsner remains a beautiful — if big at 8.8% abv and 110 IBU — tribute to the Hallertau Mittelfrueh hop. Or Mittlefrüher as it is spelled in the Halltetauer region of Bavaria.

Back for a second time, Samuel Adams Hallertau Imperial Pilsner remains a beautiful — if big at 8.8% abv and 110 IBU — tribute to the Hallertau Mittelfrueh hop. Or Mittlefrüher as it is spelled in the Halltetauer region of Bavaria.

Can he walk the walk?

Can he walk the walk? One of the many perks – beyond watching a roadrunner pace up and down the burm outside my office window right now, not quite sure what his plan is – of living where I do is that I know that the New Mexico Rio Grande Valley is not the Best.Beer.Region.On.Earth.

One of the many perks – beyond watching a roadrunner pace up and down the burm outside my office window right now, not quite sure what his plan is – of living where I do is that I know that the New Mexico Rio Grande Valley is not the Best.Beer.Region.On.Earth.