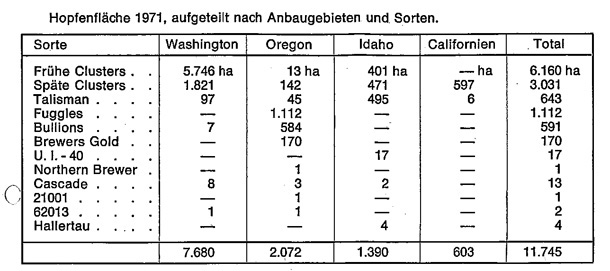

Let’s call this the state of U.S. hops 0 BC (Before Cascade).

The chart is taken from The Barth Report 1970/71. The measure is hectares, one equaling 2.47 acres. U.S. hop farmers harvested almost 46 million pounds of hops in 1970 (compared to more than 106 million in 2017) and exported about 10 million. Between September of 1970 and April of 1971 U.S. brewers imported 13.6 million pounds of hops, 88% of them from Germany and Yugoslavia (since dissolved – about one third of the hop production was in what is now Slovenia). They used imported hops for traditional, classic, some say noble, aroma and flavor. They briefly thought Cascade might serve as a substitute.

The story about the birth Cascade has been told many times (by Mitch Steele in IPA: Brewing Techniques, Recipes and the Evolution of India Pale Ale and here). After verticillium wilt devastated the Hallertau aroma crop in the early 1970s, Coors Brewing offered contracts at then-lucrative prices to support growing Cascade. By 1975 farmers in the Northwest had planted more than 4,300 acres of Cascade, or 13% of the total crop. But brewers — let’s call them pre-craft brewers — soon discovered a) the aroma wasn’t quite why they expected or wanted, and b) Cascade does not store well. “The beer tasted OK, except when the beer drinker would have another bottle of beer . . . something would come up through the nose he wasn’t familiar with,” said Al Haunold, the USDA hop geneticist at the time. “We know now that it is geraniol.”

**********

Pardon the brief interruption, but if posts like this interest you I suggest subscribing to Hop Queries, my once-a-month newsletter. It’s free.

**********

Brewers bought less Cascade, but did not abandon it altogether. Acreage peaked at 6,348 in 1981 (a number not eclipsed again until 2014) and dipped to 1,013 by 1988. Its low was 906 acres in 1999. Willamette, introduced in 1976, became the star aroma hop, mostly because of Anheuser-Busch. Only 10 years ago, farmers in Oregon and Washington grew 7,257 acres of Willamette and 2,149 of Cascade (at the time Idaho growers did not reveal how many acres they planted of any one variety, but there was little Willamette or Cascade). That was the year, of course, that InBev bought Anheuser-Busch and pulled the rug out from under Willamette.

I went digging through the numbers because a few weeks ago the USDA reported that farmers in Washington, Idaho and Oregon strung more acres of Citra (6,652) for harvest than Cascade (6,009). Brewers Association economist Bart Watson found the news tweet worthy. Bryan Roth followed up with a post at Good Beer Hunting that concluded:

“As more breweries build IPA portfolios that rely on new-age hop flavor, it might be easy to project the impact Citra will have in the future. The rapid increase of acreage already shows demand will continue to grow, but as a base hop of modern IPA in the way Cascade once was for Pale Ale and IPA, it’s cemented its status as a game changer for the industry.”

We’re most definitely not in 1971 anymore. However the rise and fall and rise again of Cascade seems good enough reason for me to avoid making any predictions. Nonetheless, I might have accidentally described Citra as a perfect hop during a recent BeerSmith podcast. That’s not only because a hop farmer recently told me, “Brewers say you can’t make a bad beer with it.” You can. I’ve tasted some. Such feedback makes growers more confident about planting additional acres. But Citra is also a means to understanding how hops contribute to the exotic flavors currently in favor. It is rich in the components — notably geraniol (same stuff generally rejected 40 years ago) and thiols (sulfur compounds) — that seem to be essential. Hop scientists will find it easier to tell us what is happening if they know where to look.

(You can read more about thiols in the August/September issue of Craft Beer & Brewing. Brewers don’t necessarily need to understand how or why oxygenated compounds and thiols do what they do if they simply use Citra all the time. It works. But if 6,000 breweries follow that formula those beers are going to start to taste an awful lot alike.)

Cascade contains the same essential oils, if at lower levels, so it is premature to suggest we are entering a post-Cascade era. It is curious that acreage began to shrink in the mid-80s at the time hundreds, then thousands, of breweries looked to Sierra Nevada Pale Ale for inspiration. It was so ubiquitous by the mid-90s there was sometimes blowback from brewers (that Citra may yet experience) ready for different flavors. Stone Brewing even made being Cascade free part of its, perhaps you would say, Stone-ness.

I’ll have more from conversations with Northwest growers about the shifting variety landscape, including the cost of swapping varieties on more than 3,500 acres (hardly unusual in the Northwest), in the next Hop Queries. Talking to farmers always reminds me of the importance of perspective and how challenging it is for them to plan for the future. So a few more numbers for perspective, and then a passage from the nineteenth century (also cited in For the Love of Hops).

– What matters most is not acres but pounds of hops harvested. Cascade yields between 12% and 25% more than Citra in Washington, where most of is grown. The comparison is a little difficult, but because Citra has been expanding so fast and first-year plants don’t yield as well, even in Washington. Bottom line, farmers may still harvest more pounds of Cascade in 2018 than Citra. For sake of comparison: Mosaic, which like Citra has been expanding quickly, yields between 14% and 34% more pounds per acre than Cascade.

– Czech farmers planned to string 10,750 acres of Saaz (compare that to 6,652 of Citra) in 2018. German farmers planned to plant 8,398 acres of Halltertau Tradition and Mittelfrüh. Sorry, no report on what actually was planted.

– U.K. farmers planted about 2,400 acres. TOTAL.

– Cascade acreage did not surpass Cluster until 2000. Cascade was near its bottom then, but Cluster was falling even quicker. You’ll see at the top that Cluster accounted for 78% of acreage in 1971.

Finally, consider this from Hop Culture in the United States, published in 1883.

“The brewing industry is not exempt from the influence of fashion. A careful survey of the types and descriptions of beers in vogue at different times, will show that fashion has had something to do with our trade. Without going back to the olden days, when our Saxon forefathers imbibed freely of ale and mentheglin made from barley and honey, without any admixture of flavoring herbs, we may refer to the period when the introduction of hops into this country gave quite a different character to the national beverage; instead of the sweet and mawkish ale, a true beer, flavored with aromatics essence of the hop, came into fashion.

“This took place in the sixteenth century, since when, hopped beers have been more or less in fashion. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, there was a great rage of black beers, and so great was it that our metropolitan brewers found their trade rapidly increased by the production of this article; porter was consumed in enormous quantities, and it seemed at the one time as if light-colored beers would become things of the past. We know now that fashion for porter and stout is in the decline. Large breweries, at one time engaged solely in the production of these specialties, have altogether discontinued the brewing of black beers.

“Toward the end of the last century and at the beginning of this, the taste of the public inclined to very strong ales. The old-fashioned stingoes and strong stock ales were consumed in large quantities and with thorough relish at this period, probably because the habits of life which then prevailed, caused the physiques of the people to be stronger than the present times. In those days, beer was brewed regardless of cost in many a household, and the modern private trade brewer had scarcely started into existence. Gradually the taste for lighter and cheaper beers grew, until the year 1851, when the great Exhibition marked an era in brewing, as it had done in other industries. The splendid productions of Messrs. Bass and Allsopp, then attracted much attention, and from that time the taste for high-hopped beers has gone on increasing until lately, when there has been an evident tendency to fall back again upon milder and less bitter beers.

“During the last two or three years, brewers have experienced a demand for beers of very low gravity, and containing less of flavor of the hops than was fashion on some twenty years since, and of course it is their bounded duty to comply with the dictate of fashion in this respect. We will not further refer to the threatened introduction of lager beer into this country, than to say fashion takes strange freaks, and it will be well for brewers to be prepared for all eventualities.”

Hop farmers as well.

Can you tell me more about those numbered hops?

My apologies for overlooking this question until now. UI-40 and 21001 went nowhere. UI-40 was obtained from an open pollinate cross of early Clusters with an unknown male. It was grown only in the Boise Valley. It’s aroma was said to be Cluster-like.

62013 became Comet. It was released to farmers in the mid-1970s as a high alpha (for the time) hop, intended for efficient bittering. Acreage peaked at 635 in 1980 declined as higher alpha hops became available. It basically disappeared, kept alive on one or two farms. Interest has been revived the last few years because of its bold, citrus aroma.