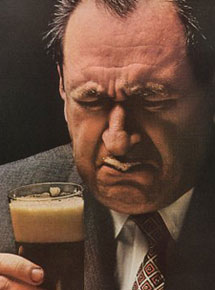

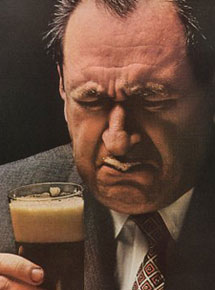

NEW BEER RULE #3: You must drink at least two servings of a beer before you pass judgment on it.

I starting writing the rule before this wandering conversation at Seen Through a Glass, but it makes a great point. In the middle there is a discussion about how, or if, drinkers come to appreciate a range of beer flavors.

I starting writing the rule before this wandering conversation at Seen Through a Glass, but it makes a great point. In the middle there is a discussion about how, or if, drinkers come to appreciate a range of beer flavors.

My answer: Pay attention.

At first I was going to propose only a single serving (that size may vary according to style). However, George Reisch of Anheuser-Busch suggests a “three pint rule” when he speaks at beer dinners. Several years ago Brooklyn Brewery’s Garrett Oliver put forward a “Four-Pint Principle” to other brewers.

Oliver explained he means “that I want the customer to WANT to have four pints of this beer.” Circumstances may dictate otherwise but he or she should want to continue drinking that beer. Oliver was speaking to brewers, telling them they needed to get out and drink their beer where other people drink.

“Just before the end of every pint, every customer makes a decision – ‘Will I have another one of these?'”

A commercial brewer got me thinking about the rule when he wrote this in an e-mail:

“My favorite rating of all time goes something like this. I went to X festival where I proceeded to drink 4 ounce samples of everything they had 55 beers in all over a 4-6 hour period. Right about the time I was set to go home, some guy broke out this beer that I (really wanted). I was so late to the bottle opening that I got only an ounce of dregs from the 4-year-old bottle of bottle conditioned and unfiltered beer. God, it was the best one-ounce tasting in my life. I can still remember seeing the light at the end of the tunnel after swallowing it…. Or it could have been that I drank so much before and I was seeing Jesus himself? Either way, I give it 19 out of 20 and it would have been a perfect score but I had trouble with its ‘clarity.'”

You can understand why he OK’d using this, but without his name. He likes the beer rating sites and appreciates they’ve been good for his business. But he knows that customers buy growlers where he works, go home to hand bottle the beer, then ship it all over the country. He knows enthusiasts will split beer into tiny portions to share with friends.

That’s not the way he intended his beer to be enjoyed. (OK, when a consumer buys the beer it becomes her property, but we’re getting the beer we do today because brewers put some of themselves into the product.)

Yes, I know that judges at the Great American Beer Festival or World Beer Cup only sample a few ounces in deciding which are the “best” beers.

No, this isn’t a screed against beer community sites – I’ve written before about how vital they are to the beer revolution. And I’d still tell you assigning a score to a beer for anything other than personal use is silly even if you guaranteed you’d drink 10 servings first.

This is a rule for your personal use.

Reserving judgment isn’t going to make a great beer taste mediocre, nor a boring one suddenly take on nuance. Reserving judgment means paying attention throughout – whether it is a beer high in alcohol, low in alcohol, high in hops, low in hops, malt forward, malt backward, yeast dominated, yeast sublimated. What’s the rest of the story?

You might be surprised what you learn. Besides you got nothin’ to lose. I’m giving you a reason to have another beer.

NEW BEER RULE #2: A beer consumer should not be allowed to drink a beer with IBU higher than her or his IQ.

NEW BEER RULE #1: When you open a beer for a vertical tasting and there is rust under the cap it’s time to seriously lower your expectations for what’s inside the bottle.

I’m beginning to realize there is a chance I will break down and try Miller Chill. Got to be curious, right? Check out the number of posts at Beer Therapy. Somebody is feeling the passion.

I’m beginning to realize there is a chance I will break down and try Miller Chill. Got to be curious, right? Check out the number of posts at Beer Therapy. Somebody is feeling the passion. Don’t forget to stock up on some Mild ale for Friday.

Don’t forget to stock up on some Mild ale for Friday.

I starting writing the rule before this wandering conversation at

I starting writing the rule before this wandering conversation at  So you are entitled to think this carries the same sort of authority as the recent report funded by MySpace that found MySpace is a great marketing platform. Personally, I favor giving credit to the guild for trying to change the image of beer (sound familiar?) and to think that similar research in the United States would show that there’s a good-sized market for stories of a beery nature.

So you are entitled to think this carries the same sort of authority as the recent report funded by MySpace that found MySpace is a great marketing platform. Personally, I favor giving credit to the guild for trying to change the image of beer (sound familiar?) and to think that similar research in the United States would show that there’s a good-sized market for stories of a beery nature.