An interesting exchange of comments at the Portland Beer Blog regarding the Widmer-Redhook merger. Summarizing the two views:

One side: “The ruin of the American Beer revolution may be paved by over sizing, takeovers and greed.”

The other: (From Vasilios Gletsos of BJ’s Brewery) “I feel this is a short cut to thinking, and promotes a mythical narrative to the history and growth of the beer industry . . .” You really need to read it all.

The debate about if size matters (no, not like the e-mails you have sitting in your spam folder) ain’t going away. See Small, the New Big – and beer, a post from 20 months ago that quotes from a debate from 10 years before, one that had already been going on for 10 years.

The debate about if size matters (no, not like the e-mails you have sitting in your spam folder) ain’t going away. See Small, the New Big – and beer, a post from 20 months ago that quotes from a debate from 10 years before, one that had already been going on for 10 years.

Phil Markowski addressed the issue last week while talking about the decision by Southampton Bottling to strike an alliance with Pabst Brewing. As a result he will direct brewing of some of his brands at the Lion Brewery. “It’s less romantic, but the perception that you can’t make good beer on a large scale is wrong,” he said.

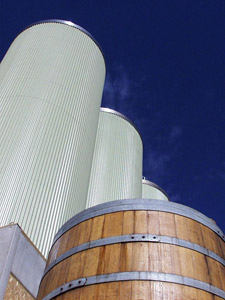

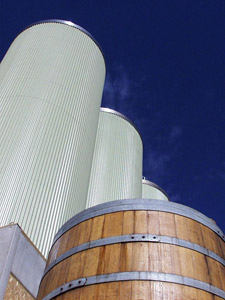

In my head I’m a journalist and I know he is right. Those New Belgium Brewing conditioning tanks pictured above hold 2,100 hectoliters (more than 55,000 gallons each), and New Belgium has grown to be bigger than the Lion. The primary fermentation tanks at Duvel Moortgat in Belgium hold 1,000 hectoliters each. I have Duvel in my beer fridge.

In my heart I’m enough of a beer romantic to make Journalist Stan nervous.

My interest in the role of place in a beer; the how and the why; the ingredients and process . . . is, on the one hand, basic curiosity — and desire to find a story you won’t fall asleep to before I finish. On the other hand, these things represent emotional attachment to an idea of artisanship that many, maybe even me, relate to production size.

If you’re still with me give this, The artisanal movement, and 10 things that define it, a read. Lost Abbey brewmaster Tomme Arthur, whose batches are basically small and smaller, passed it along a while ago and I think it helps to frame this conversation.

Each item on the list might be worth a blog post, but for now I’m claiming the first: A preference for things that are human scale.

Scroll back to the picture above. It’s from 2000, the year New Belgium installed the 2,100 hecto tanks and had its first four 60 hecto wood vats (“foedres”) delivered. Shortly thereafter the brewery acquired six 130 hecto foedres. Now six more are on the way. The tanks mostly yield La Foile, but also a variety of other even-harder-to-find wild beers. As impressive as the brewery’s tank farm will be with the new additions, its wood capacity still won’t equal one of those big tanks on top.

I’d call La Foile production human scale.

The outdoor area where those four foedres sat a few days while they were “swelled” (filled with water) long ago was encompassed by one of many brewery expansions.

New Belgium Brewing has grown into a big place, and a busy place. It wouldn’t be accurate to have described it as a ghost brewery last June on the weekend Widespread Panic was playing at nearby Red Rocks, but it sure was less crowded. It happens every year; Panic comes to Red Rocks and everybody wants off.

Eric Salazar does his best to accommodate them. Salazar and his wife, Lauren, manage the NBB barrel program, but that’s only part of their jobs. She oversees quality control and he works in the brewhouse, including production and scheduling logistics. He didn’t even pretend to complain a few days after the concert when he talked about the juggling involved.

“Maybe there’s going to come a time we can’t do this,” he said, “but I hope not.”

Makes you think that big and human scale don’t have to be exclusive.

We’ve got

We’ve got

A Bell’s beer by any other name is probably still a Bell’s beer, right?

A Bell’s beer by any other name is probably still a Bell’s beer, right? The debate about if size matters (no, not like the e-mails you have sitting in your spam folder) ain’t going away. See

The debate about if size matters (no, not like the e-mails you have sitting in your spam folder) ain’t going away. See