They kept turning their head.

Meanwhile, in case you didn’t get the memo, no Monday links today.

Waimea Canyon awaits.

They kept turning their head.

Meanwhile, in case you didn’t get the memo, no Monday links today.

Waimea Canyon awaits.

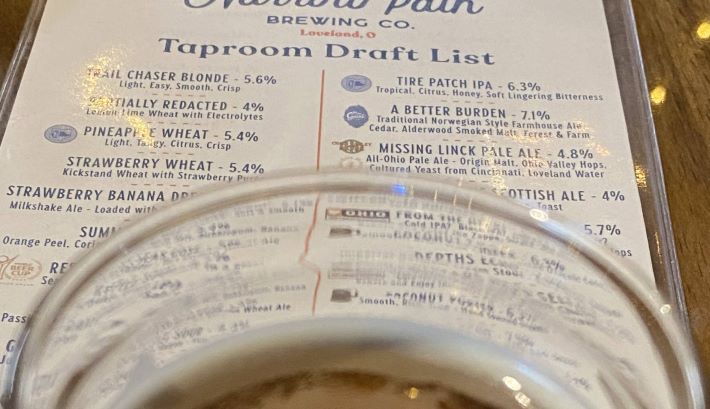

The description of A Better Burden on the menu at Narrow Path Brewing outside of Cincinnati lists the ingredients, then two words: Forest & Farm.

“Those words are my attempt to help the ones tasting the beer to envision and place themselves within a setting,” Narrow Path owner/brewer Chad Powers explained. “That description is a hopeful reminder to folks that this beer has true origins in our natural world and that the resulting liquid is as much an offering from the land as it is from the brewer.”

A Better Burden is on my “Best in 2023” list in the current issue of Craft Beer & Brewing magazine. I expect you understand that means it was one of the beers I enjoyed most from a universe of choices I had not tasted previously. Otherwise, the “best” list would be scattered with well known, and deserving, beers such at Rochefort 8. Nine of the 10 beers described were new to me; the exception being Urban Chestnut Stammtisch. (The collection of contributors’ lists is also available in podcast form.)

I’m writing about A Better Burden because 70 words in the magazine did not seem like enough about this combination of smoke and cedar that I find sublime, and many other people may not. A Better Burden is a collaboration between Narrow Path and Nine Giant Brewing, and Powers and Mike Albarella have brewed it together at Narrow Path the past three years.

They had both read ”Historical Brewing Techniques” by Lars Marius Garshol right when the book became available. They wrote the initial recipe together and have subtly changed it each year. The base malt and the alder wood smoked malt come from Sugar Creek Malt Co. in Indiana. “We knew that Caleb (Michalke) had built a Såinnhus, and we wanted to use ingredients that were as local as possible and that were produced as traditionally as possible,” Powers said.

They chose his Stjørdal malt knowing it would be the most polarizing ingredient in the grain bill. Smoke is particularly assertive in this batch.

Powers harvests the cedar every year from the same hillside across the river in Kentucky. “A good friend of mine is an ecologist at Eastern Kentucky University, and he oversees several conservancies across the state,” Powers said. The friend plants seeds while Powers cuts off the ends of branches. “I like to do it when the weather is cool and brisk but also when there’s enough sun to feel some warmth on my face.”

The first year they fermented the beer with a commercially available Voss kveik strain. The last two years we’ve used strains that were not, until recently, commercially available. Caleb Ochs-Naderer, now the program chair of the brewing science program at Cincinnati State, was brewing at Nine Giant when they brewed the beer the second and third time.

He has been a long-time kveik fan/evangelist, and traveled to a homebrew gathering in Norway several years ago. He brought back a catalog of dried kveik that he stored in his freezer. “We selected a strain called Stalljen because it was described as saison-like without any phenolic notes. We rehydrated the yeast from their dried flaked state and fermented in the upper 80s to low 90s,” Powers said.

“I think the thing I love most about the beer is that it certainly makes me feel something, often several things. The time and effort spent harvesting the cedar with my friend realigns my heart to a deeper connection and purpose in brewing.

“I think the thing I love most about the beer is that it certainly makes me feel something, often several things. The time and effort spent harvesting the cedar with my friend realigns my heart to a deeper connection and purpose in brewing.

“I can feel the sun on my face as I’m reaching to trim a branch in the cool autumn air. I can feel the wind on my face as I give thanks to the grove of trees that play such an important part in the entire experience. Something in me awakens each time I sip.”

(Nine Giant often takes names of beers from song lyrics. Powers was looking through Nordic and Viking poems/chants and found a translation of Hávamál that had the phrase “a better burden” in it. “That idea and the specific turn of phrase resonated with me.”)

Monday beer links will (probably) return Dec. 4. I plan to post a few thoughts here before then, but turn to Alan McLeod on Thursdays and Boak & Bailey on Saturdays for links to interesting beer related reading.

A decade ago, Asheville, North Carolina, provided New Belgium Brewing with $3.5 million in tax reimbursements as part of incentives to locate its second brewery not far from downtown. The city of Vista, California, has made breweries an important part of its economic development plan.

There are plenty more examples of cities recruiting breweries. But after reading “One polarizing brewery, six figures’ worth of tax incentives” you might pause and ask yourselves who much is it worth to you to have a brewery built in your home town.

Simply for pleasure . . .

Wandering the backstreets of Cologne in search of interesting boozers. “Might there be another Lommi or two lurking, round the back of a laundrette, near a discount supermarket, where the trams turn round?” Cue Tom Russell and “Back Streets of Love.”

. . . or not

The Beer Nut pulls no punches. “I find it difficult to believe that even the most ardent haze-pilled fanboi will enjoy what’s on offer here.”

Fortunately, there is always a next beer. “But much as it shouldn’t work, it’s absolutely beautiful, showing a lot of the joyous features of export-strength stout, but with lots of fresh hop topnotes. I’ll take another one like this, please.”

You might also enjoy

Fonio Rising

Brooklyn Brewery is releasing a beer made with the West African grain fonio.

“No fertilizers, no irrigation, no pesticides, no insecticides, no fungicides—- nothing. Whether you look at it from an environmental perspective, a social benefit perspective for the farming communities, or from a brewing perspective, fonio is so good that it seems like someone must have just made it up,” said brewmaster Garrett Oliver. “But fonio is real, and Africa grows 700,000 tons of it every year. Fonio is easy to brew with and gives beautiful flavors to beer.

“This is very exciting stuff, and I can easily envision a future where fonio is widely used as an everyday brewing ingredient, bringing vast benefits to brewers, beer drinkers, farmers and the planet.”

Yes to brewers using a sustainable grain grown near where they make beer. Shipping it all over the world? Not quite as sustainable.

The Legacy of Double Diamond Burton Pale Ale

To which I will add, in the mid-90s in the Midwest many “good beer bars” served a Double Diamond, which was imported from the UK. At the Union Jack Pub in Indianapolis they pulled it from a tap handle that suggested it was a cask ale (it was not). Its most prominent feature, no matter where you tried it, was diacetyl.

What’s So Special About Extra Special Bitter, Anyway?

An aside, Double Diamond was often billed, again in the Midwest, an ESB (it was not even close). If ESB is to be more than an oddity drinkers who crave it should know there are locations where they will find it on all the time. My top three choices in Denver-ish are: Sawtooth Ale (granted, a bitter, but as Left Hand Brewing boasts, it is “timeless”) at Left Hand Rino; Chosen Family ESB at Lady Justice Brewing; and cask-conditioned Hogshead Brewery Chin Wag (pictured at the top along with Gilpin Black Gold, a porter).

Pale ales, American IPA & Hazy IPA; that’s it?

Jeff Alworth asks “what were the watershed beers that transformed American beer in this craft era?” Not to be a contrarian, but I prefer to spend time considering the ones he calls the “character actors of the beer world.” Find me a beer that is as interesting as the work of everyone on this list.

A Beer’s Birthplace Is No Longer the Be-All and End-All

Moving on, and being a contrarian . . . Drinkers might be drawn to the beers mentioned in this story because of their import cache, but they are better because they are brewed locally. Thus, birthplace matters.

12 Mistakes You’re Making When Visiting A Brewery

AI written? Consider, for instance, No. 2, Dressing inappropriately. “As a rule of thumb, it’s a good idea to dress for a brewery as if you were dressing for a construction site. While you won’t need to bring your own hard hat and high-vis jacket – breweries tend to provide these if it’s considered necessary – durable, closed-toe shoes with a grippy sole are a must if you’re going for a walk on the brewery floor.” And you just wanted to sit down and enjoy a beer.

One alcoholic drink can shift your morality.

Who finances research like this? This one “discovered intoxicated participants had a greater willingness to consider engaging in impure behaviour, such as attending an event where participants act like animals, ‘crawling around naked and urinating on stage.'”

Back to your Monday morning. Have a productive week. I’ll be out of the country much of it and am not certain if I will be posting links next Monday.

Earlier this week, the BBC posted a story asking a provocative question, “Would you drink genetically modified beer?” That set a different tone for the story than would a headline that reads, “Why wouldn’t you drink a genetically modified beer?” That’s because GMO (genetically modified organism) is a topic perfectly suited for not so well thought out, screaming at the top of our voices, exchanges on X.

And it introduces a question about why more attention has not been paid to the use “thiolized” (a term that Chicago-based Omega Yeast has trademarked) yeast strains play in creating tropical flavors such as guava and passion fruit that have played such an important role in the popularity of IPAs.

Backing up for a moment, it was only two decades ago that a scientist in Japan established that sulfur compounds in hops, known as thiols, contribute to unique aromas found in then new cultivars such as Simcoe and Citra. The race was on to find more varieties that would do the same and to understand what was happening.

And it was less than a decade ago that scientists in France and Belgium published research showing barley malt also contains thiols precursors. Unlike some of the thiols in some hop varieties, those thiols are “bound.” In fact, many hop varieties also contain bound thiols.

Most yeast strains are not particularly good at freeing bound thiols—that is, making them flavor active—in grain or hops, if they do at all. Modified strains from Berkeley Yeast and Omega Yeast are.

It is not really that simple, but I don’t want to bury you in science or turn this into a long read. Thiols are complicated. Genetic modification is complicated. Some of your homework, in this case related to thiols, is behind a paywall at Brewing Industry Guide, but here is a free-to-read primer from 2018. Likewise, The New York Times reported on what Charles Denby was up to in 2018.

And both Omega and Berkeley provide excellent explanations on their website about how they engineer their strains. I recommend this page at Omega or this one.

Miskatonic Brewing in suburban Chicago first used Cosmic Punch before Omega gave it a name. Founder and brewer Josh Mowry had a pretty good idea of how CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology works. “We pretty quickly did some dives into what the concerns are. What are the known unknowns,” he said. He shared what he learned with customers. “We’ve only had a couple people raise (doubts), say that it feels unnatural.”

Nonetheless, it seems relevant to remember that not long ago breweries that would call their products craft hesitated to use enzymes. Jack McAuliffe took a stand early. When Frank Prial of the New York Times visited New Albion Brewing in 1979, he wrote, “McAuliffe boasts that his beer is a completely natural product. ‘We use malt, hops, water and yeast,’ he said. ‘There are no enzymes.’”

If high gravity beers didn’t establish that has changed, Brut IPAs certainly did.

Plenty of brewers embraced modified yeast strains just as quickly. Have they all gone out of their way to inform consumers that the strain in this beer may be different than the strain in that beer? Of course not.

Quite honestly, I’m not sure they think it is important. In a conversation with a brewer last Friday, after he mentioned the Berkeley strain in the beer I was drinking the discussion did not then turn to genetics. Instead, we talked about what portion of the thiols might have come from barley malt and what portion from hops. (Yep, you did not want to be there for that.)

However, members of the brewing industry understand this is an important topic. Last year, four authors examined the terminology, science and regulation of genetically engineered yeast across seven pages in MBAA Technical Quarterly. Trust me, it was technical. The authors examine the topic from multiple views, acknowledging the “positives of genetic engineering are not without rigorous debate on innovation and safety concerns.”

However . . . “The world, and indeed the whole of the brewing industry, is now catching up to the environmental reality that agricultural producers have been facing for the past several decades. With the rapid increase in the global population and the rising challenges of climate change, biotechnology offers significant advantages that may be crucial to sustainability.”

The year before, in another TQ issue (Vol. 58, no. 2), White Labs founder Chris White wrote about both sides of the genetic engineering debate. He concluded by focusing on transparency:

“The rise of plant-based meat products is a good example of how truth in labeling operates for much of the food and beverage industry. There are currently lawsuits from manufacturers over what they have to put on the label. They are fighting over the use of the word “meat,” the font size, and more. The brewing industry is much more transparent with what they put on the label.

“If you use GMO yeast, should you tell the consumer on the label or description? I would say ‘yes,’ that we should stay on the side of transparency.

“It is not about whether it is right or wrong, or if it is good or bad for us. It is about communicating our passion and pride to the consumer—not what labeling laws say we have to do. That can be what the rest of the food and beverage industry focuses on.”