Questions about barley prices in the short term keep popping up and it is no small deal for breweries. However if Brewers Association members are going to sell 20 percent of the beer brewed in the United States in 2020 there’s a bigger conversation at hand.

Bart Watson and Chris Swersey only mentioned malt production in passing during their presentation at the American Hop Convention, because they were there to talk, obviously, about hops. They drew a contrast to how quickly hop farmers have reacted to growing demand from all brewers for what they refer to as “aroma” hops. They are planting different varieties and building out infrastructure. Swersey and Watson added considerable detail about both hops and barley in the current issue of New Brewer magazine, the publication for BA members.

… there is already increasing evidence that the demand for malt grown and malted specifically for all-malt beer production has not been met by domestic malsters. … Further, much of the malting capacity developed during the 20th century was capitalized and owned by large brewing companies and this continues today. This makes the malt industry less flexible than the hop industry.

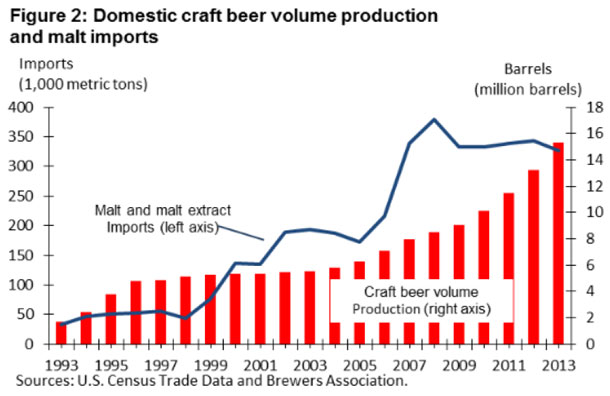

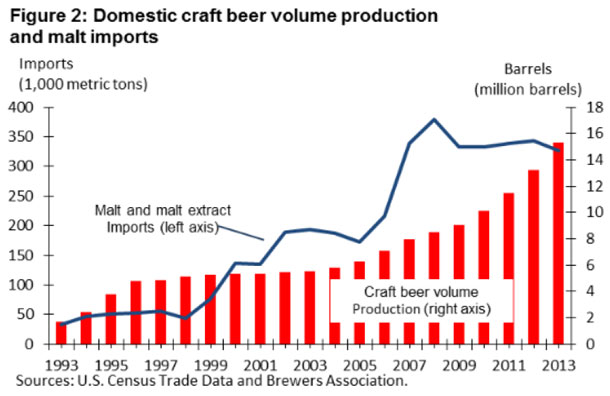

What they refer to as the disconnect between BA member demand and U.S. malt supply can be seen in the increasing share of imported malt used by domestic brewers. There are several reasons for an increase in imported malt, shown in the chart at the top. Much of the malt is coming from Canada, in part because barley growing has moved north as a result of climate change. American brewers would much prefer to use malt grown somewhere in North America, and to have input on what is grown.

Processing will be just as big a deal. Like with hops, the investment extends beyond the fields.

Current estimates of U.S. malting capacity show the ability to malt between 2.2 and 2.3 million metric tons annually. given that the U.S. malting infrastructure is used not only to supply domestic demand but also Mexican brewers, industry insiders see total production as using 95 percent of that current annual capacity, but much of that capacity is committed and unavailable to craft brewers. Our analysis of consumption and production confirms that current uncommitted U.S. malting capacity is unable to meet current craft demand.

They project that brewers of all sizes will use 25 percent more malt by 2020. They figure the cost of expanding capacity will be $500 million at a minimum.

I remember attending a seminar at the 2007 Craft Brewers Conference, so we are talking not quite eight years ago, where the discussion focused on the cost of stainless steel and what it would take to build enough brewing capacity for BA members to reach ten percent market share. Simpler times, I guess.

Brett Domue of Our Tasty Travels has announced the topic for The Session #97: Up-and-Coming Beer Locations.

Brett Domue of Our Tasty Travels has announced the topic for The Session #97: Up-and-Coming Beer Locations.