So now I have a better answer for the question when homebrewers ask me where they can buy various kinds of hop extract. Although there are a limited number of extracts available from homebrew stores, both local and online, they don’t equal the range of what Kalsec is selling at Amazon.

There is a catch. Kalsec’s 8-ounce bottles cost $70 or more and are intended to dose 50 to 75 barrels (or about 1,500 to 2,300 gallons). Dosing is a challenge, so patience is a requirement when making a group purchase with the idea of parceling out the extract. To be honest, I haven’t wrapped my head around the logistics. Be sure to check out the dosing manual.

You’ll find the Kalsec products described at their web site, but here’s a bit more to think about:

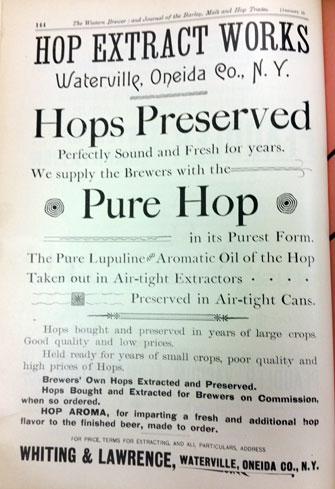

– Hop extracts are not exactly new. The New York Hop Extract Company built the first extraction plant in the world large enough to produce quantities sufficient to supply brewers in 1870. Brewers bought extract when hops were plentiful and prices low as insurance against poor crop years and high prices, using it in combination with whole hops.

– Hop extracts are not exactly new. The New York Hop Extract Company built the first extraction plant in the world large enough to produce quantities sufficient to supply brewers in 1870. Brewers bought extract when hops were plentiful and prices low as insurance against poor crop years and high prices, using it in combination with whole hops.

– Scientists used water and ethanol to extract hops in the nineteenth century. Today most processors employ carbon dioxide extraction, either supercritical (Europe and the United States) or liquid (England).

– It wasn’t long ago that anybody who called herself a craft brewer considered extracts the antithesis of natural hops. They were an efficient, in other words cheap, way to bitter beers that had little hop character. Vinnie Cilurzo at Russian River Brewing was the first to speak openly about using CO2 extract. Initially he brewed Pliny the Elder, a groundbreaking double IPA, using only hop pellets. He didn’t like grassy, chlorophyll flavors he attributed to sheer hop mass. Following a suggestion from Gerard Lemmens at Yakima Chief, he replaced pellets with extract for the bittering addition.

“We kept it secret for the first few years,” Cilurzo said, “but Gerard twisted my arm.” Cilurzo gave Lemmens permission to publish the information in a Yakima Chief newsletter. Scores of other small breweries soon began to use CO2 extract.

Jeremy Marshall, who is in charge of brewing at Lagunitas, said the brewery started using extract in a wider range of its beers in 2010, intent on lowering the level of tannins in several brands (a problem that emerged after a poor barley crop). “We use hop extract because it increases the quality of our beer,” he said.

– American brewers are not nearly as open when discussing use of extracts for aroma and flavor as for bittering. Several brewers I talked for two stories for Beer Advocate magazine about the future demand for hops said they expect to be using more fractionated hops in the future, but didn’t want to be the first. The reverse is true in England, said Chris Daws at Botanix, a subsidiary of global hop merchant Barth Haas. Botanix creates its own line of aroma extracts, as does Hopsteiner. Daws said craft brewers in the UK are not reticent to use fractions for aroma, but resist extract for bittering.

– Extraction is totally different than distillation, the process Sierra Nevada to get the oils it adds to Hop Hunter IPA (link is for a YouTube video).

– These are intended to supplement “regular” hopping. A complaint about extracts is they can taste artificial, and they do better with a little help. Read the instructions for dosing on a commercial level to see is not as simple as spiking a beer with raw hop oil. And there is the matter of cleanup.

– The list of both positives and negatives that commercial breweries take into account is lengthy. So I’ll cut to the chase and quote Cilurzo again: “It’s such a personal decision. It’s philosophical.”

To return the conversation to homebrewing, I like the freedom that comes with using whole hops (well, pellets) — seeing how particular varieties interact with each other and with yeast to create new aromas and flavors, ones not available from extracts, at least for now. So I’m not necessarily endorsing the use of extracts at home or commercially (on the other hand it’s not like I’d have to tell my children to eat eight per cent less because dry hopping results, on average, in eight percent beer loss).

But I’ve dosed finished beers with samples Kalsec sent and served them to homebrewers. It’s fun. They ask where they can get something similar. Now I have an answer.

““We use hop extract because it increases the quality of our beer,” he said.”

But quality can only be altered, not increased.

It’s interesting that the Kalsec products are blends of different hops–and in the case of the Witty blend, hops and botanicals. (Anyway, I assume so–it’s made for witbiers.) I don’t know how many breweries will want off-the-shelf ready-blends of hops, but possibly there’s a market for that. As a homebrewer, I’d be more interested in single strains–Amarillo, for example.

Commercial breweries can contract for single variety extracts – including Amarillo, so maybe you need to start making more friends ;>)

These investigations, at Kalsec and elsewhere, are going in all sort of directions. Some people simply want more linalool (and that’s available from Botanix).

So, if my math is correct, one would add .50-.75 gms in 5 gallon batch?

In theory. Notice that is a 50% difference.