This was by no means a deluge. You could almost count the early morning raindrops hitting the tent roof. There’s one where Orion would be located, a couple by the Big Dipper. Rain and wind can be a very bad thing at a hop farm this time of year. A few days earlier rain and wind in Washington and southern Idaho had knocked down about 140 acres of hop trellises.

Rain wouldn’t be a problem this day in northern Idaho. And, to be honest, it somehow disappointed me. I didn’t really want to see an entire hop yard come down and thousands of pounds of cones laid to waste, but when you’ve been sleeping in a tent, albeit a fancy one, with Amarillo hops to the south of you and Amarillo hops to the west then it is easy to expect something else you’ve never seen might happen.

I was one of 15 people who write about beer invited by Goose Island Beer Co. and Anheuser-Busch to visit Elk Mountain Farm, north of Bonner’s Ferry, Idaho, in mid-August, so first a bit of disclosure. The trip included transportation to and from the farm, two breakfasts, one very impressive beer dinner, one equally impressive lunch, one audacious beer dinner, lots of beer, and personal tents big enough to accommodate a queen-size bed, dresser, and table and chairs suitable for entertaining.

(Listening to my tent rustle lightly in the wind the second morning, my stomach still painfully full as a result of that audacious dinner, I thought about a passage that appeared in Harper’s magazine in 1885. “Hop-pickers expect to live on the fat of the farmer’s land, and, as a rule, they are not disappointed,” the reporter wrote. “Whole sheep and beeves vanish like manna before the Israelites in the short three weeks that follow, while gallons of coffee, firkins of butter, barrels of flour, and sugar by the hundredweight are swallowed up in the capacious maw of the small army.”)

“We wanted to show people what a wonderful place this is, a special place,” Goose Island brewmaster Brett Porter said, explaining the idea for the trip originated at the Chicago brewery. Hops are second nature to Porter. He visited hop fields in Oregon and Washington regularly as a brewer in his native Oregon. He speaks fondly about learning the rituals related to hop selection, where brewers evaluate the current crop and choose the lots of hops they will use the following year, when he was a brewing apprentice in England. Instead of talking about his relationship with hops he’d rather find a way for them to speak for themselves.

In reality two farms located about 10 miles apart, Elk Mountain sprawls along the Kootenay River, shadowed by three mountain ranges, the Selkirk Range to the west abruptly rising about 6,000 feet above the valley floor. The view is more striking when dark green hop bines heavy with bright yellow-green cones hang from the massive trellis system than when the ground is covered with canola plants, as it was in 2010 and 2011. Growing hops and growing canola are both acts of agriculture, but only one has a rich history, magical aromas, and memories associated with beer. Hops also mean more jobs in Boundary County, and every one matters in a sparely populated county with 11,000 residents.

That’s good enough explanation for the smile on Elk Mountain general manager Ed Atkins’ face when he talks about Goose Island’s brewers and how happy he is to be growing hops for them. He is not a man to use a dozen words when two will do, but at least three times during the first evening our group visited the farm he began sentences, “I can’t say enough about Goose Island and …” It would be an overstatement to say that the brewery “saved” Elk Mountain as a hop farm. However it certainly is a different place at this moment than it would be had Anheuser-Busch InBev not purchased Goose Island in 2011, creating a need for several varieties the farm had not previously grown.

Atkins went to work at Elk Mountain in 1986, when Anheuser-Busch bought 1,500 acres of farmland and announced plans to open the farm, which now covers 3,000 acres, with 1,700 of those under trellis. (Under trellis simply means the poles and wire are in place to grow hops – even though there have been rumblings about possible upcoming hop shortages today you can find corn, wheat, garlic and other crops planted under trellis in Oregon in Washington.)

Anheuser-Busch InBev began reducing hop inventory in 2008, shortly after InBev acquired Anheuser-Busch. Previously A-B rather famously kept years worth of hop stocks. AB InBev rewrote contracts, often on generous terms but nonetheless dramatically reducing the amount of new hops they’d buy until they wound down the inventory. Between 2008 and 2009 acreage of Strisselspalt in France was cut in half, as was Halltertau Mittelfrüh in Germany. Farmers in Oregon grew almost 2,600 acres of Willamette in 2008 and Washington farmers more than 4,600. Last year, they strung 553 acres in Oregon and 522 in Washington. That’s the context in which acreage at Elk Mountain shrunk more than 80 percent. (The farm was back to 1,300 acres of hops under trellis when harvest began last week.)

These days farmers in Washington and Oregon report they are talking to Anheuser-Busch about new contracts for Willamette or hop varieties the brewery might use instead, such at Mount Rainier, most notably for use in top selling beers like Budweiser and Bud Light. Sales of those brands are down in the United States, but are growing impressively internationally.

Farmers first planted hops in southern Idaho in the 1930s, and today Idaho produces almost 10 percent of the hops grown in the United States. It wasn’t until the 1970s that a consortium established the first farm near Bonner’s Ferry, 450 miles to the north of other farms. They picked the site in part because it is parallel to the Halltertau region of German, where disease threatened the future of Hallertauer Mittelfrüh.

Since it opened its own farm A-B has always emphasized the latitude, almost 49 degrees north compared to 45 degrees in Oregon, not insignificant because hops are day length sensitive (photoperiodic).

(The International Hop Growers Convention conducted a study in 1983 that illustrates the importance of growing cultivars with day length requirements suited to where they are planted. In the trial cultivars with a common female parent that had been bred and selected in England, Germany, or Yugoslavia, at latitudes of 51°, 48°, and 46°, respectively, were all grown in those three countries, and also in France at 47°. The cultivars flowered earliest in the lower latitudes, the difference between Yugoslavia and England being 10 to 14 days. The English and Yugoslav plants both showed a steady reduction in yield as the sites became more remote from their place of origin.)

When Porter, rubbing Amarillo hops pulled off a nearby bine, explains that varieties grown at Elk Mountain traditionally contain higher levels of essential oils than the same varieties grown elsewhere it’s a different conversation than when then CEO August Busch III would boast about the quality of Mittelfrüh from the farm. The cultivars fueling consumer interest in hop-centric beers, most of which have “IPA” somewhere in their name or description, contain a higher percentage of oils (measured in milligrams per hundred grams of cone weight) than landrace varieties like Mittelfrüh or Saaz.

Saaz, for instance, usually will have one-half to one percent oils, compared to more than 4 percent in Equinox, a variety new in 2014. Brewers ask farmers to coax all they can out of popular varieties, products of cross breeding, like Cascade (up to 3%), Centennial (up to 2.5%) or Amarillo (up to 2%), all of which are among 10 grown in meaningful amounts at Elk Mountain. Farmers may do this by letting the hops mature longer or drying them more gently (which more time consuming and expensive). It helps when terroir gives them a running head start.

By the time acreage at Elk Mountain farm reached 1,700 in the early 1990s harvest required a work force of 380. Advancements in technology, necessary in part because recruiting laborers continues to get harder, reduced the number needed by about 160. About 140 migrant workers, many of them not so temporary, will manage the harvest this year, but more will be needed if hops are planted on the remaining acres under trellis. Some workers have been returning for more than 20 years, staying from March until November. Although harvest is the time of year outsiders pay attention to hop farms there’s less photogenic work, like replacing trellises or hanging string that hops will grow on, for a good portion of the year.

The farm provides free housing, there’s a well-kept playground next to the apartments, day care is offered, and the nearby schools are bilingual. After hop plants are trained to string in the spring the workers may leave to pick cherries, then return to harvest hops. They’ll leave after harvest to prune fruit trees in Washington’s Yakima Valley.

Given that a day doesn’t seem to pass without a discussion popping up about what constitutes “craft” in craft beer, it is curious to these seasonal workers described as unskilled. They have a variety of specialized skills, entirely different more valuable than those of “hop pickers.”

Those were unskilled laborers. Machines began doing the picking more than 60 years ago, allowing the physical act of plucking cones off bines to take on a romanticized patina. Some of that was washed away in recent years as small farms popped up around the country. Volunteers recruited to pick hops for those farms, or perhaps a local brewery, have learned there is little skill involved and it’s not really a fun way to pass a day (maybe one day, hanging out with friends, and eventually throwing some beer into the mix, but certainly not two).

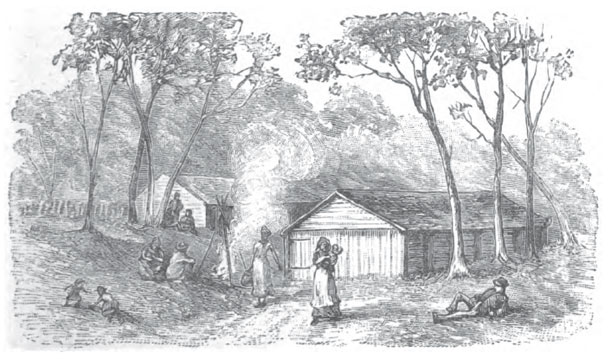

But these romantic images live on in postcards and historical societies in the regions where hops were grown in the nineteenth centuries — that includes much of the United States as well as other countries.

Author George Orwell simultaneously debunked the notion that picking hops made for a holiday with pay and acknowledged the romantic aspect in an essay for New Statesman & Nation in 1931, writing: “There is no pleasanter place than the shady lanes of hops, with their bitter scent—an unutterably refreshing scent, like a wind blowing from oceans of cool beer. It would be almost ideal if one could only earn a living at it.”

“Hops and Hop-Pickers,” published by The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge published in 1883 as part of a campaign to improve living conditions for migrant workers in England during hop harvest, offers a healthy dose of reality. Author Rev. J.Y. Stratton compared lodgings of mid century to “dog-hole” dens and hovels.

The hopper-house (pictured above) more common by the time the book was published was a definite upgrade. Each bricked building, with a tiled roof but no windows, included 10 or more rooms, generally ten to fourteen feet square. The floors were covered with a thin layer of straw, but it was up to hop pickers to provides rugs, plus blankets for sleeping. They hung their clothes on pegs at night, occasionally had lanterns but more often candles, and provided their own bowls or pans in which to wash their clothiers and faces.

Tenants were often given a choice between staying in a hopper-house and based on this description it is hard to imagine why any would have picked tents:

“As the rain came busily down, the water would slowly and surely penetrate through the brushwood or hop-bine on which the straw for bedding was placed. The drip, which no crazy umbrella or tattered shawl could resist, came freely through the canvas, which being no longer serviceable for the use of our hardy veterans had been sold, ‘old government stores, second-hand tents, cheap, and worthy the attention of hop-growers.’ The condition of the wretched inmates, men, women, and children, in a reeking and steaming atmosphere, in which the wet from above recruited the puddle which gradually arose from below, was pitiable in the extreme. The marquee extemporized out of the rickcloth upreared on a crazy pole, to which the scared and weary occupants clung while the canvas flapped and banged in the howling midnight wind, and which, notwithstanding their efforts, would all come down about their ears, and deprive them of their poor shelter, was not much better.”

It’s just as well that much related to hop farming has changed. I love vivid memories and images of hand picking hops – particularly on oral history kept at the hop museum in Poperinge, Belgium, in which Bertin Deneire, who became a teacher and also a museum guide, recalls picking hops in the 1950s – but it’s good to review “Hops and Hop-Pickers” from time to time.

General manager Ed Atkins (right) explains how a picking machine works while farm manager John Solt looks on.

After the first rows of Saaz hops had been picked at Elk Mountain last week and begun to dry in the expansive kilns their bright aromas filled the building. Porter grabbed a handful, smiled broadly as he crushed the hops between the heels of his palms, and stuck his nose inside his cupped hands.

Outside, farm manager John Solt waited patiently to ferry trip participants from the kiln to the campground. “He’ll be here until he sniffs every one up his nose,” Solt said, sounding not at all exasperated. He’s seen this before. August Busch III used to visit the farm twice a year, once at harvest time and on the Fourth of July. “It was his vacation.”

Solt’s mother was a foreman on the farm that preceded it. When he was in grade school he’d get off the bus at the farm to hop chores the season called for. It beat bailing hay. He lived briefly in Colorado, working as a logger, but returned to work at Elk Mountain as soon as the farm began operations. He’s doesn’t share the recollections that Deneire has of a final day of harvest in Belgium when community members picked by hand, nor would he wax nearly as romantic, but his day-to-day relationship with hops is in fact stronger.

“Goggle-eyed I used to stare at this incredible spectacle. Elderly people whirling like dervishes, falling over after a wild waltz. Men slapping young girls’ bottoms, fat women sweating profusely,” Deneire recalled. “The boisterous atmosphere in the farmhouse became sultry with the perspiration of this ‘madding crowd,’ and soon we would leave the room and follow the foreman into the dark of night. Singing and in droves we went back to the field to witness the hop guy (a straw dummy) being ‘hanged’ from the last pole of the field and set alight with a burning torch made from a rolled-up newspaper. In a way it looked like an execution, our revenge against nature for weeks of pent-up frustration and endless toil under the burning sun. And we would dance and sing around the guy until the last embers of the bonfire had died out.”

Canola just doesn’t inspire the same sort of memories.