MONDAY BEER LINKS, MUSING 04.27.15

Why craft brewing is about to go to war with itself.

Does the modern American beer industry (and the culture attached to it) represent the leading edge of a new capitalism?

So it turns out Thrillist is not all click bait and listicles. Dave Infante dots his i’s and crosses his t’s in a relentless march to this conclusion: “In the end, the industry’s individuality and cohesion just doesn’t matter as much to many (I’d argue most) consumers as it does to some brewers. And as that becomes more apparent, more brewers — heavily armed with increased production and aggressive marketing bought with the help of outside cash — will make a play for the shelves and taps that are right in front of the mainstream consumer.” Hence war.

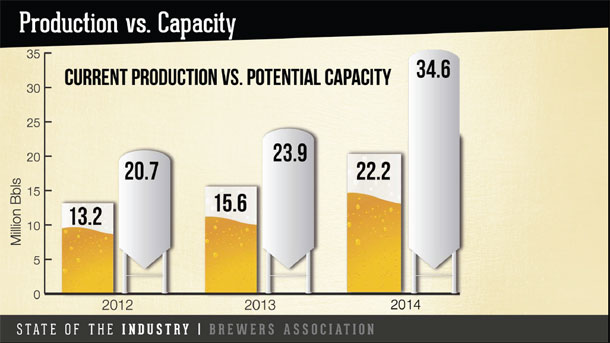

I’ll throw in this chart from The 2015 State of the Industry presentation at the Craft Brewers Conference just to be provocative. Unused capacity is not good for pricing, and there seems to be more each year. However, that 12.4 million barrel difference between capacity and production in 2014 needs to be considered in context. Production was 64 percent of capacity in 2012 and two years later production exceeded 2012 capacity. In 2014, capacity was once again 64 percent of production. In addition, there is little doubt that 2015 production will exceed 2013 capacity.

That doesn’t invalidate Infante’s conclusion, but it does mean one potential concern isn’t, for now. So back to the question in hand, if his prediction is accurate how deep do the price cuts reach? Is the battle limited to the breweries Alan McLeod calls big craft? Infante mentions what he calls the noncombatants, those that stay small. If that includes all the microbreweries (producing less than 15,000 barrels) and brewpubs operating at the end of 2014, we’re talking 3,218 of the 3,418 breweries the Brewers Association defines as craft, or 94 percent. Now, some of those will grow past 15,000 barrels in 2015 and many others have similar aspirations, but you sense a larger number will feel the fall out if the pricing gloves come off.

But is it inevitable? That’s why the second link. Last January, Maureen Ogle wrote about the beer-related book she’d write if she were writing one (she is not). In that one she’d ask, “Does the modern American beer industry (and the culture attached to it) represent the leading edge of a new capitalism?” and “Is modern American brewing a new kind of ‘industry’? Or is it more of the same and that sameness will become apparent once the first two generations of modern brewers retire and/or sell their operations?” [Via Thrillist and Maureen Ogle]

Have we reached peak geek?

A short post from Ed Wray, related specifically to the UK and geeks as a source of funding for brewery expansion. However, Ray Bailey reminds us via a comment that non-geeks, even non-beer drinkers, see the growth in sales of what is generally referred to as craft beer presenting an investment opportunity. That’s because non-geeks are drinking these beers. A virtuous cycle or a game musical chairs? [Via Ed’s Beer Site]

Some CBC 2015 thoughts, questions, and takeaways.

As Jon Abernathy points out, sustainability was one of the themes the Craft Brewers Conference, and much of the post-conference discussion has focused on the “can growth be sustained?” aspect. Jon folds in the environmental component. [Via The Brew Site]

Dead or Alive: Are single-hopped beers still interesting?

Yes. Next question. [Via Chris Hall]

Types of UK Brewery.

Consider it a learning excercise. I’d like to see something analogous attempted on this side of the Atlantic, as long as it doesn’t result in a diagram printed on T-shirts. [Via Boak & Bailey’s Beer Blog]

The Accidental Death of the Wine Writer.

“Rather than being the spur to further discourse, wine writing has become a quasi-professional end in itself, and thus is rarely adventurous, controversial, intellectually provocative or emotionally engaging.” Is beer writing any different? [Via Les Caves De Pyrene]

Tricking Women Into Drinking Beer : Lies Men Tell.

5 Reasons Why The Beer Wench Is Bad For Beer.

Dueling lists. [Via Thrillist and Northdown Taproom]

I don’t think the American craft beer industry is a new kind of industry. It is a product of the capitalist system as any other service or product component of the economy is. The choice and innovative spirit we all benefit from issue from this fact. However, the industry does benefit from some unique features – features that are interest ingto identify including their history but which don’t (IMO) have a defining influence on areas such as growth or pricing.

More than anything connected to a “hippie” ethos, I’d argue that two factors gave the early industry a particular stamp:

i) the spread and legalization of home brewing, which has a long history and was practiced by people of different backgrounds; and

ii) the influence of a non-brewer, the writer Michael Jackson, who became an avatar and advocate.

Normally, an industry knows what to produce and innovation comes solely from within. Jackson gave a production template to the nascent industry – others helped but he was hugely important. This and home brewing with its related competitions and instruction tomes (e.g. Charlie’s, very influential) created a sense of community most businesses lack.

Some would argue brewing, due to the nature of the product made, has always enjoyed a special form of community. I don’t think that’s really true, e.g. the macro beer industry has been famously combative for decades.

Ken Grossman was a home brewer. So Jack McAuliffe. But otherwise they had quite different backgrounds, one a middle class kid who liked bikes and tinkering, the other a widely travelled Navy man who also liked tinkering. Jim Koch did not home brew and had advanced degrees in business and law. Creemore in Canada, now owned by Molson-Coors, was set up by a group led by a gent named Wiggins who had a long history in the advertising business – nothing to do with home brewing certainly.

All kind of backgrounds informed the industry but a home brewing and Jackson-led community ethic had good influence in the early years and of course played a large role in the formation of the BA and the BJCP categories. Apart from this though, to me the industry looks like any normal one with a similar pattern of growth and competition. The real factor which makes it different today from other industries is the regulatory structure, the 3-tiered system in the U.S. for example or various kinds of past and present labelling and composition laws. But vestiges of the community elements remain, for example, when BBC brewed a revival of New Albion Pale Ale as a tribute to Jack McAuliffe.

Gary Gillman

Gary – If it is not a new kind of industry are price wars inevitable?

Yes I think so. We already seeing e.g., Goose Island mixed packs, and SN Pale Ale, sold inexpensively in relative terms. In time this kind of pricing pressure may lead to a winnowing of stand-alone craft breweries. But brewpubs are in a different position because they have higher margins and are also restaurants. Also, in some markets, the normal pricing dynamics don’t apply. In Ontario, there is a floor retail price for beer set by the government…

Gary Gillman

Plus you are seeing an increase in the 1998-esque “new economy” assertion in the form of the entirely unwarranted $24 mixed grocery store12-pack from Stone in NNY as well as the wishery from Allagash that we now equate beer with a $50 bottle of wine. It’s this sort of nonsense that big craft might have actually come to believe that may bring this down upon their heads. There is no war, just the folly that something is new about an oligopoly facing smaller more nimble actual competitors. Which one might expect from the dinosaurs who go so far as framing their trade association PR as the writings of an economist.

Man, I hope price wars are inevitable. I don’t see any non-BMC beer for under $10 a six-pack anymore, and folks like Three Floyds and Ballast Point are all in the $14-16 a sixer range. I can’t justify those prices on my budget beyond special occasions. Finally some of the “big craft” breweries are experimenting with 12-packs or cases and adjusting prices downwards accordingly, and occasionally those get the supermarket sale prices. If Sierra Nevada or Stone or Bells or Great Lakes can cut prices and still make money, cheers to them.

Honestly, these “craft beer is a new kind of capitalism” strikes me as the very same dot.com era Kool-Aid, where people were going around saying “it’s a new economy”. It clearly wasn’t, and if you applied traditional economics to dot.com business models, it became obvious something things weren’t adding up, and eventually, reality hit. The same is true with the rapidly growing market of craft beer. Traditional economics explains what we are seeing and there are plenty of counter-examples to this “we’re all in this together” ethos beginning to flare up as breweries inevitably start treading on each others turf. In my never humble opinion, anyone suggesting craft beer represents some new kind of capitalism either doesn’t understand capitalism, or isn’t paying close enough attention.

That mixed 12-pack of Stone’s is $18-19 in the Chicago area, so unless we think they’re intentionally selling at a loss in the Midwest (giggle, snort), we know they can make money at lower prices. Which is why I’m rooting for a price war or “correction” — if what keeps a brewery’s real estate on the shelf is lower prices, good for me, he says, selfishly and happily. I have no problem with folks charging what they can — it’s working for Three Floyds, and I’ll cherish the memory of enjoying their beers until I was priced out — but am ready for actual competition and the realization that lower prices will be necessary if folks want to keep shelf space and tap handles.

I am encouraged by BrewDog announcing an Ohio branch plant. A big craft brewery outside of the BA circle should shake things up,

Will be very interesting to see where their prices land.

Based on their global revenue stream likely exactly where they need price to be to build a second U.S. branch plant.

We’re seeing much lower prices in Portland than those I hear of in other parts of the country. No standard sixers are more than ten bucks, and sale prices (common) are more like 8.50-9. You can’t get away charging $20 for a bomber here, and all but the rarest releases are in the 5-12 dollar range.

All of this conforms to the expectations of standard competitive markets. Some breweries have adopted a low-price model that means there are always $4 bombers and $7-8 sixers on shelves. It tethers all the prices from shooting up. It’s one of the reason non-Oregon breweries don’t sell here– they’re used to much higher margins elsewhere.

Thanks for the link Stan!