My new desktop background.

place/local/ingredients/sensory

Because foeders & indigenous

All About Beer posted a story yesterday about foeders (or foudres should you prefer the French spelling to the Dutch) and the Foeder for Thought Festival today in Florida.

All About Beer posted a story yesterday about foeders (or foudres should you prefer the French spelling to the Dutch) and the Foeder for Thought Festival today in Florida.

I point to this primarily, to be honest, so I have an excuse to use this photo. I think I have posted it here before, but I like it. It was taken at New Belgium Brewing in June 2000. The brewery had recently taken delivery of its first four 60-barrel foeders (it now has 64, many of them larger). The tanks were outside because they were being swelled (filled with water) to make them beertight before they were filled.

This tank didn’t take to swelling all that well, and my back got soaked while I captured this image. Not long before New Belgium had put its first 2,000 hectoliter tanks (about 1,700 barrels, or twice what the average brewpub produces in a year) into place. They are in the background.

The AAB story features Foeder Crafters of America prominently. They are local*, and I wrote about them for Beer Advocate magazine last July. Their business has really taken off since Nathan Zeender of Right Proper Brewing and I visited them last April. That’s Nathan on the right in the photo below and Matt Walters of Foeder Crafters on the left.

Nathan and Phil Wymore from Perennial Ales* will be talking about foeders in one of the Salons at SAVOR in June. Here’s the whole skinny about Foeder Beer: A Search for Delicious, “Perennial Artisan Ales of St. Louis and Right Proper Brewing Co. of Washington, DC both use large oak foeders as a conduit for the expression of their house mixed-fermentation cultures. The goal is characterful beers with layers of complexity and charm. For the vast majority of the human endeavor of fermentation, wood vessels were the medium—these current-day foeder beers are really more revivalist than innovative. Taste the results of their experimentation with four unique beers.”

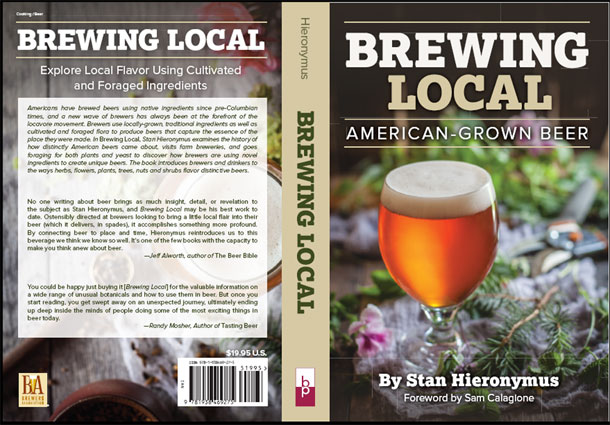

You can catch that and still have time for Indigenous American Beers – Past & Present at 9:30. Again, the description, “What did the first beers brewed in America taste like? Join Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head Craft Brewery and ‘Brewing Local’ author Stan Hieronymus as they provide insight into the beers Native Americans had been making for hundreds of years before Columbus arrived. Sample beers recreated from ancient recipes—once you try all three, Stan and Sam are sure you will agree that militant beer laws like the ‘Reinheitsgebot’ and pants are equally cumbersome and unnecessary. They invite you to wear a loincloth or one of those sweet brewer’s kilts to this seminar in a show of solidarity.”

* Perennial Ales is also local, meaning St. Louis, Missouri. I point this out because yesterday I was talking to a college student who noticed my cell has a New Mexico area code. I explained I live in St. Louis and he asked where St. Louis is located.

Ales Through the Ages, March 18-20

A weekend of beer and history in Colonial Williamsburg, with a speaker lineup that includes Randy Mosher, Martyn Cornell, Ron Pattinson, Mitch Steele, Tom Kehoe and other people more interesting than you realize (plus me, so there’s the disclaimer).

A weekend of beer and history in Colonial Williamsburg, with a speaker lineup that includes Randy Mosher, Martyn Cornell, Ron Pattinson, Mitch Steele, Tom Kehoe and other people more interesting than you realize (plus me, so there’s the disclaimer).

You need to need more? “Ales through the Ages offers a journey through the history of beer with some of the world’s top beer scholars. We will explore ancient ales and indigenous beers of the past, examine the origins and consequences of industrial brewing, discover the ingredients brewers have used through time, and share a toast to brewers past.”

I’m not sure where else on earth you’ll be able to see Martyn Cornell, Mitch Steele, and Ron Pattinson give presentations on a Sunday morning. (Here’s the whole program.)

So pardon the plug for an event I’m speaking at. Even though it’s not until March 18-20 I thought you’d want to know about it. Registration is already open.

Because somebody’s pouring a beer made with pineapple weed

“All truly great thoughts are conceived by walking.”

“All truly great thoughts are conceived by walking.”

– Friedrich Nietzsche

I choose the Beers Made By Walking Festival. There may be 12 or 18 or some silly number of events happening in Denver the day before the Great American Beer Festival, and I guarantee you the What The Funk? Invitational will be more crowded. Probably others as well. But when I saw BMBW had moved to Wednesday evening, I redid my travel plans to get to Denver on Wednesday.

The two hours I had to spend at last year’s festival were my favorite two hours of the long weekend. This year I can hang around for the whole event, beginning at 4:30 and lasting until 8 p.m.

Eric Steen started BMBW in 2011 and since then he and others have led brewers and other interested parties on hikes in many different regions. The premise is simple. They ask brewers to go on nature hikes and brew a beer inspired by the trails. Often the result is what Steen calls a “placed-based beer.” Often the beers include ingredients found along the trail. Sometimes not, but what was clear last year is there’s a connection between the brewers and the beers, one that can be contagious.

The result makes for some great eavesdropping, a chance to collect stories without asking questions. Just listening.

The festival starts 4:30 p.m. at the outside space of Our Mutual Friend Brewing Co., about a mile and a half north of the Colorado Convention Center.

Beers Made By Walking Beer List

Bonfire Brewing – Sagebrush Juniper Saison – An ode to the high desert with inspiration from Bellyache Ridge in Eagle, CO.

Boulder Beer – Honey Hips Brown Ale – Honey brown ale brewed with pine nuts, toasted sunflower seeds, wildflower honey, and rose hips added. Inspired by an urban hike through Boulder with Gone Feral.

Breckenridge Brewery – Gooseberry Gose – Inspired by a stroll down Main Street Breckenridge, the tartness from the gooseberries adds complexity to this salty and already sour beer style.

Crazy Mountain Brewing – Naughty Pine – Inspired by a hike at West Lake Creek Road in Edwards, this pale ale includes 25 pounds of pine needles in place of finishing hops and was aged in Breckenridge Bourbon barrels.

Crooked Stave Artisan Beer Project – TBA

Dry Dock Brewing – Hampden Corner Lavender Saison – A crisp saison with lavender harvested right by the brewery.

Elevation Beer Co – Wild Raspberry and Mint Porter – A porter brewed with both wild raspberries and wild mint harvested near Boss Lake.

FATE Brewing – WILD Flower Honey Wheat – The same great honey-wheat beer we brought to BMBW two years ago, inspired by a hike in Boulder’s Chautauqua Park. It has been aged with Brettanomyces in oak for two years.

Fiction Beer Co. – Brett Saison with Rose Hips – A dry, crisp, and refreshing saison brewed with 5 pounds of rose hips at the end of the boil and Brettanomyces.

Fieldhouse Brewing – Squawbush Saison – Made with berries from the indigenous squawbush, they provide a strawberry lemonade-like flavor and sourness to the already tart saison.

Fonta Flora Brewery – TBA

Fonta Flora (In Collaboration with Jester King) – TBA

Former Future Brewing – Sour Red Rye – Inspired by a stroll in the hills of North Carolina, this base beer was aged on blackberries, raspberries, and honey.

Horse & Dragon Brewing – Perambulation Ale II – An American Amber Ale brewed with dandelion root and leaf as well as yarrow flower.

Great Divide Brewing – Rosabelle – Inspired by a walk in Matthews/Winters Park near Red Rocks with the Museum of Nature and Science, this beer is a sour blend aged on plums.

New Belgium Brewing (In Collaboration with Bird Song, Free Range, Heist, and NoDa) – Yours & Mine – A Belgian Golden brewed with beet sugar (a beet sugar plant once occupied NBB’s grounds), lavender from NBB’s property, Colorado sunflowers, and Scuppernong grapes (the state fruit of North Carolina)

Odd 13 Brewing – Gooseberry Saison – Inspired by a walk in Cañon City on a hot July day, gooseberries were added to a sour Saison aged in Chardonnay barrels and then dry-hopped.

Odell Brewing – TBA

Our Mutual Friend Brewing – A wine-barrel fermented Belgian Pale Ale with Colorado wildflower honey and all Colorado wort.

Perennial Artisan Ales (In Collaboration with Scratch) – Carya Ovata – Wee Heavy brewed with toasted hickory bark, collected and toasted at Scratch’s hometown of Ava in a brick oven and brewed at Perennial. Carya Ovata is the Latin name for the Shagbark Hickory.

Riff Raff Brewing – Spruce Juice – Colonial style ale brewed with the new growth from Spruce trees, inspired by trails in the surrounding San Juan Mountains.

Riff Raff Brewing – Juniper Sage – A light bodied, refreshing ale brewed with locally harvested juniper and sage, inspired by a trip along the New Mexico border near Navajo Lake.

Scratch Brewing – Pink Granite Glade Stein Beer – A Stein Beer brewed with pink granite rocks which were heated in white oak embers, added to boil the wort once white hot and then bittered with shortleaf pine, cedar, coreopsis blossoms, wild quinine, and a small addition of hops. Inspired by a hike at the Castor River Shut-ins in the Saint Francois Mountains

Spangalang Brewery – Cucumber Gose inspired by a Denver Urban Garden and The Real Dill.

Stone Brewing – Coffee Milk Stout with Chocolate Mint Inspired by chocolate mint growing locally on Stone Farms.

Strange Craft Beer- TBA

Trinity Brewing – Menacing Chokecherry – Crafted in the spirit of wild harvest. Featuring a feral Brettanomyces strain, aged on rhubarb and wild Colorado chokecherries.

Trinity Brewing – Menacing Huckleberry – A beer only made possible when these berries are ready for harvest, this beer is also aged on rhubarb with a wild brettanomyces yeast strain.

TRVE Brewing – TBA

Wicked Weed Brewing – Terra Locale: Brettaberry – A tart farmhouse ale inspired by freshly baked berry pie. Featuring a half-pound per gallon of strawberries, blueberries, and blackberries, the acidity of the berries with the rustic funk of our house culture are rounded by the flaky crust finish of Haw Creek Honey, Riverbend Pilsner and wheat malts. From our summer memories to yours, cheers.

Wicked Weed Brewing – Terra Locale: Horti-Glory – A tart, farmhouse ale brewed with Riverbend Malt and fermented with our house culture of Bettanomyces. The addition of seasonal elderflowers, hyssop, and honeysuckle transform the rustic house culture into a lovely floral brett saison.

Wild Woods Brewery (In Collaboration with Very Nice Brewing Company) – Pale Ale with Pineapple Weed and Rose Hips. Inspired by the friendship and proximity of these two breweries, this beer opens up with big floral and citrus notes.

Wit’s End Brewing – Irish Red with Heather and Peated Malt. Inspired by an international walk on the Cliffs of Moher, this Irish Red includes a healthy addition of the perennial shrub and special malt.

Session #100: What makes a beer historically accurate?

Reuben Gray hosts the 100th gathering of The Session and asks blogs to write about “Resurrecting Lost Beer Styles.” Visit his site for links to other contributions.

When David Pierce set out to brew the first commercial batch of Kentucky Common in, well nobody knows how many, years “it was still back when we all thought it (had been) a sour beer.” That was 1994 and Pierce was brewmaster at Bluegrass Brewing Co. in Louisville.

When David Pierce set out to brew the first commercial batch of Kentucky Common in, well nobody knows how many, years “it was still back when we all thought it (had been) a sour beer.” That was 1994 and Pierce was brewmaster at Bluegrass Brewing Co. in Louisville.

We’ve since learned the idea that the process used to brew Kentucky Common in the early years of the twentieth century included a sour mash is just plain wrong. But, going on the best information anybody had to offer, Pierce began with a 100 percent sour mash, mashing in hot one night and arriving to a horrific smell at the brewery the next day. It was not an easy beer to sell. Roger Baylor at Rich O’s Public House in New Albany, across the Ohio River from Louisville, did his best to support a beer he thought was historically important. He promoted it as “beer formaggio.”

Pierce made the beer periodically in the following years before he left BBC to work for Baylor at New Albanian Brewing. He refined the process, souring only part of the mash, creating a beer than wasn’t as pungent. He thought the fifth, and last, batch was probably the best. “We couldn’t give it a way,” he said. Then somebody suggested they call it a Belgian sour brown ale. The last seven barrels (14 kegs) sold out in a week.

In the years since, meticulous research by Leah Dienes, Dibbs Harting, and Conrad Selle established that if Kentucky Common occasionally turned out sour in the marketplace in the years before Prohibition it wasn’t on purpose, and it certainly wasn’t made using a sour mash. That is reflected in the recently released BJCP Style Guidelines. Kentucky Common is in Category 27, Historical Beers, and the guidelines even specify “Enter soured versions in American Wild Ale.” That works fine for judging in a homebrew competition, particularly in a historic context, but what about modern day commercial beers? Kentucky Common now has a 20-year history in which a sour mash is used in the brewing process.

Granted the modern history is limited. However, if you are looking for a “Kentucky Common” brewed in Kentucky and sold outside of Kentucky it is going to be Against the Grain’s Kamen Knuddeln, which is a blend of a young sour-mashed beer and a barrel-aged stout. Jerry Gnagy gets a lactobacillus starter from Four Roses Bourbon for the sour mash. It makes perfect sense that had Kentucky Common been brewed continuously for a hundred-and-some years that it might evolved or at least different versions would have emerged. Using lacto from a nearby distillery? Makes sense. Include a portion of beer aged in bourbon barrels? Also indigenous.

Last month, as part of the Derby City Brewfest it hosted, Bluegrass Brewing invited participating breweries to make a Kentucky Common. Eight Commons ended on offer, some sour, some not. Because we were in Kentucky the following week I got a chance drink several of them. I certainly could have wasted a larger chunk of an afternoon than I did drinking New Albanian’s Phoenix Kentucky Komon and chatting with Baylor (who has currently stepped away from the business while he runs for mayor of New Albany). It is not an easy beer to make, and the brewery does it just once a year on its smaller four-barrel system — yes, four barrels a year; like I wrote, a pretty limited modern history. “It’s one of my roughest mashes of the year,” brewer Ben Minton said, in this case because of the percentage of corn and temperamental false bottom in the mash tun. “It comes out a little different every time.”

Two historic (in other words, not sour) versions I had at Apocalypse Brewing were equally delightful. Dienes had her Oertel’s 1912, which is based on the records in Oertel’s brewing logs and the only example of the style in the BJCP guidelines, on tap. Harting brought his homebrewed version. It is the only beer he struggles to keep on tap. “Oh dad, can I take a common home?” Harting said, quoting one of his children. “I’m sure it was a fabulous bucket (growler) beer,” he added.

This works for me. Kentucky Common of the past. Kentucky Common of the present. Kentucky Common of the future. There doesn’t have to be just one.