Note: Boak & Bailey periodically invite bloggers to post something longer than usual. This is my contribution.

*****

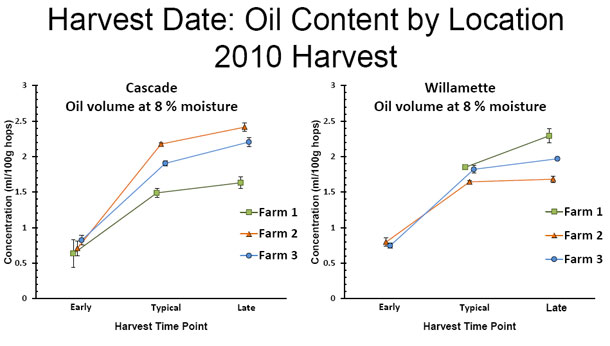

Conducting a study during the 2010 hop harvest in the Willamette Valley, researchers at Oregon State University’s Shellhammer Lab discovered something outside of the focus of the trials.

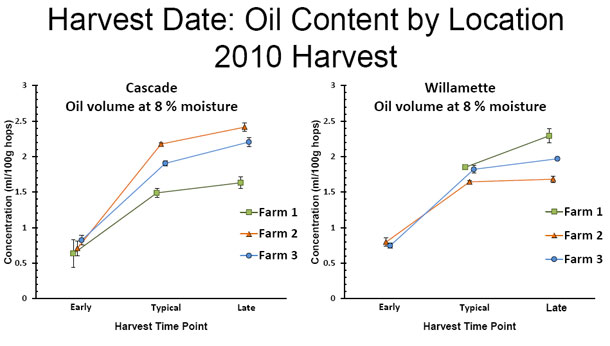

As well as learning about the impact harvest date has on hop oil content — considerable and important — they saw that concentration of essential oils varied in a way that did not suggest a single one of three farms involved was “best” for growing hops. Instead, the variety Cascade had a larger volume of oil at one location (Farm 2 in the illustration below) and the variety Willamette at another (Farm 1).

Hop farmers long ago learned that hops well suited to one region might not do as well in another. Refugees from Flanders established England’s first modern hop gardens relatively early in the sixteenth century, planting Flemish Red Bine hops. They did not produce desirable lupulin or much of it in English soil. Brewers likewise determined that the aromas of particular varieties were more to their liking from certain regions. So the research at OSU substantiates some of what is intuitive. Watermelons grow better some places than others, as do roses, basil, and carrots. Oh, and grapes. The variations are at the heart of what winemakers call terroir.

The significant difference in oil content on farms located just miles apart has wider implications. Most of the hundreds of odor compounds hops produce come from the essential oils. They further interact with yeast, the biotransformations creating still more odor compounds. The compounds, in turn, are responsible for aroma, and what constitutes desirable aromas in beer has broadened considerably in the past 40 years.

Hop scientists and brewers still have much to sort out, and more oil itself doesn’t guarantee anything. Cracking the code on how the composition of oils in a hop such as Citra or in one like Saaz impacts odor compounds will allow brewers to fine tune the way they use varieties, or more accurately a combination of varieties, to create beers that have currently fashionable flavors and aromas.

For example, research supported by Japanese brewer Sapporo has examined how geraniol metabolism might add to citrus and related flavors in beer. In one experiment, a team headed by Kiyoshi Takoi brewed two beers, using Citra hops in one and coriander seeds in the other because both are rich in geraniol and linalool. The finished Citra beer contained not only linalool and geraniol but also citronellol, which had been converted from geraniol during fermentation. The same transformation from geraniol into citronellol (perceived as rose-like, lime, other citrus, or peach) occurred during fermentation of the beer made with coriander.

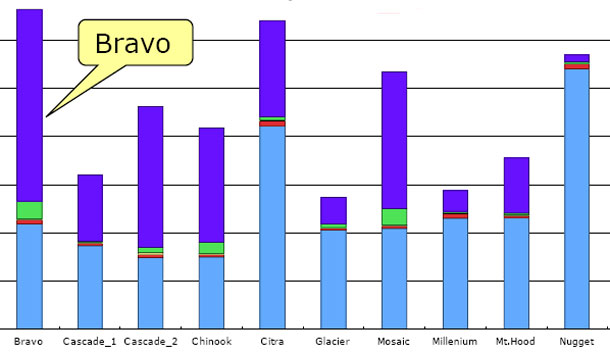

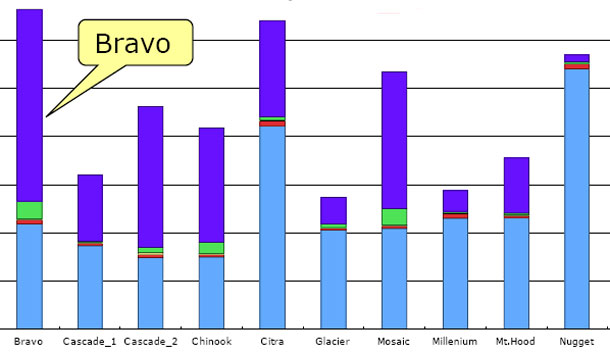

The scientists at Sapporo followed up with an investigation into the behavior of geraniol and citronellol under various hopping conditions and with various blends of hops. They identified several hops of American heritage rich in geraniol. They also looked for varieties with an excess of linalool. Some of those are shown here.

(Light blue is linalool, red is terpineol, yellow citronellol, green nerol, and dark blue geraniol)

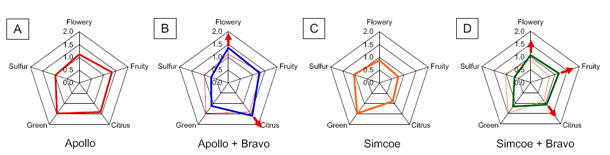

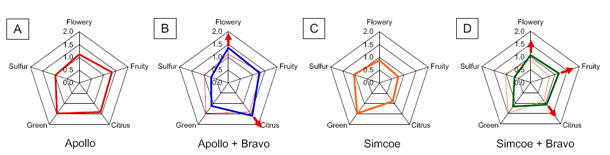

Bravo is highlighted because of its high geraniol content and because in the study Bravo was blended with Apollo in one test and Simcoe in another. A test panel described the beers blended with Bravo to be more flowery, fruity and citrus-like than the unblended beers.

Cascade, Chinook, Citra and Mosaic are all rich in geraniol, but notice that the two Cascade samples are different. They both came from Washington’s Yakima Valley. The differences are no doubt larger, at least on average, between Cascade grown in Yakima and Cascade from Oregon or Idaho. And what about from New York, Minnesota, Michigan and all the other states where farmers recently began growing hops? Or from New Zealand, Germany, Brazil and England?

Some of the differences are for the same environmental reasons grapes grown in the Napa Valley are more highly valued than those from Missouri, but with hops latitude is particularly important. Researchers realized only early in the twentieth century that day length controlled flowering plants, describing them as “photoperiodic.” While plants will grow between latitudes 30º and 52º, they thrive between 45º and 50º.

In 1983, the International Hop Growers Convention conducted a study that illustrated the importance of growing cultivars with day length requirements suited to where they are planted. In the trial cultivars with a common female parent that had been bred and selected in England, Germany, or Yugoslavia, at latitudes of 51°, 48°, and 46°, respectively, were all grown in those three countries, and also in France at 47°. The cultivars flowered earliest in the lower latitudes, the difference between Yugoslavia and England being 10 to 14 days. The English and Yugoslav plants both showed a steady reduction in yield as the sites became more remote from their place of origin.

Differences such as the ones the Shellhammer lab discovered illustrate latitude isn’t the only determining factor in why the hop grown here isn’t quite like the one grown there. John Henning, the research plant geneticist at the United State Department of Agriculture offices in Oregon, explained that environment and epigenetics combine to make hops from a particular area unique. All plant species have methylated DNA, which causes some genes to be “switched on” more easily than others. Differences in soil, temperatures, amount of rainfall, and terrain all may influence the methylation process. The underlying DNA does not change, but the methylation pattern can be different.

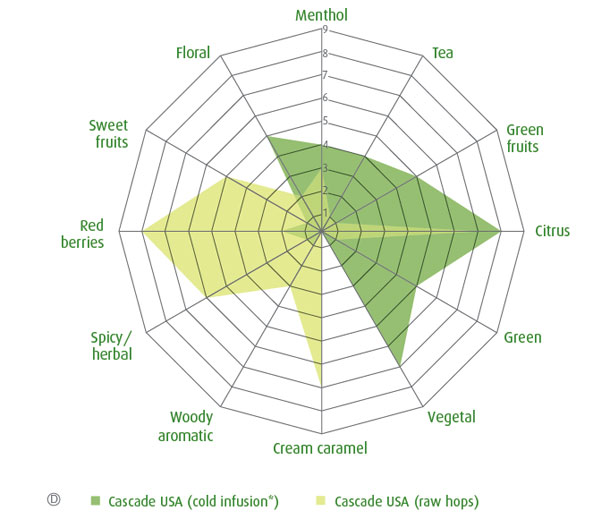

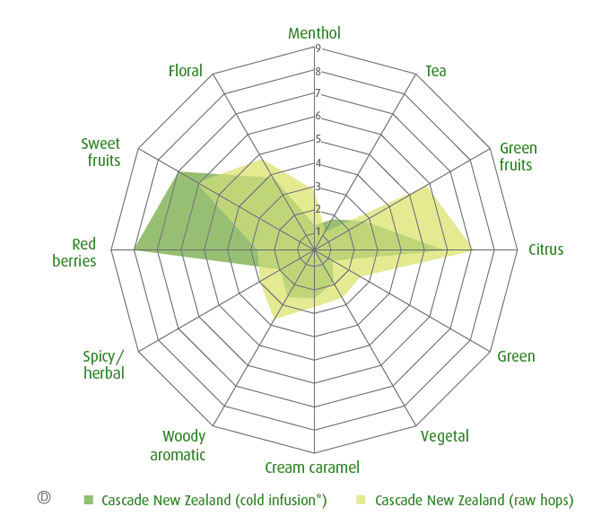

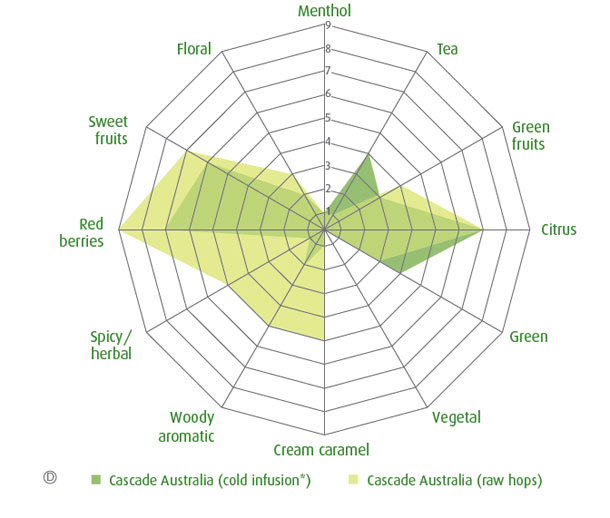

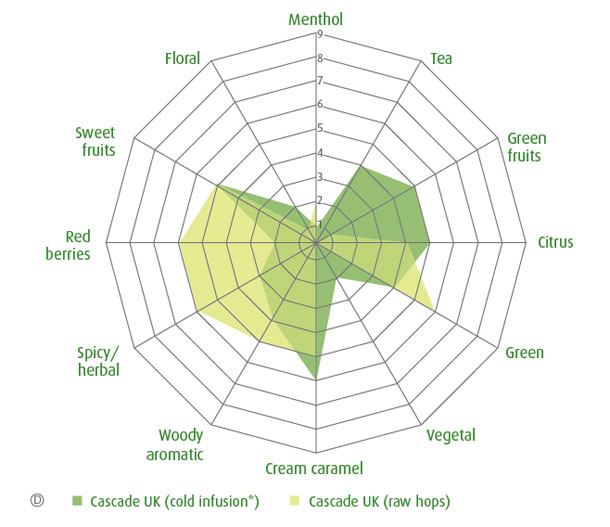

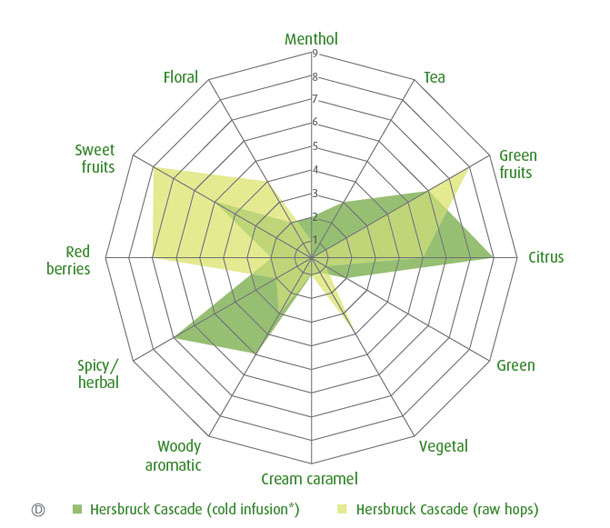

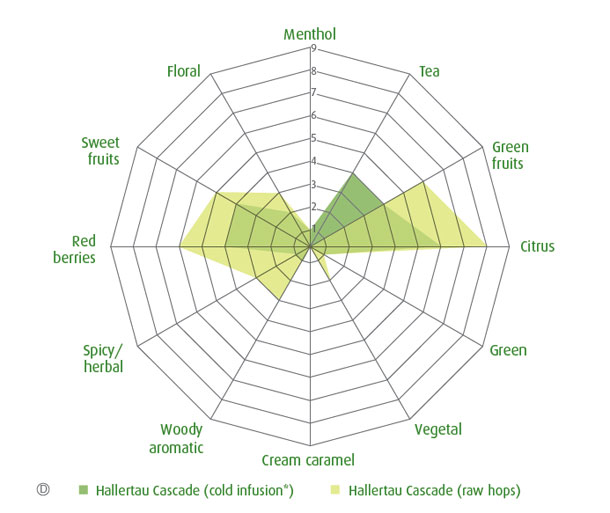

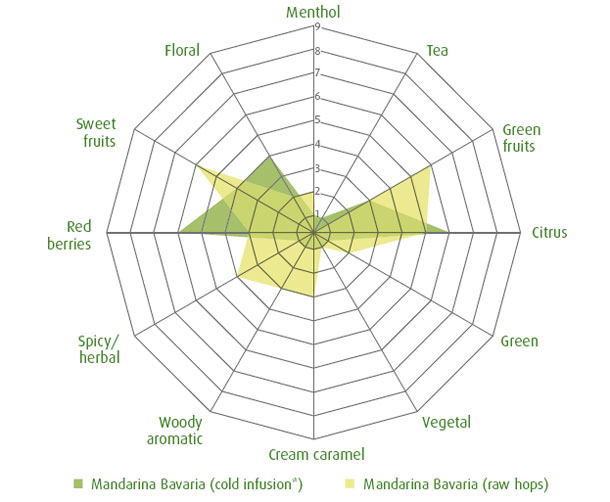

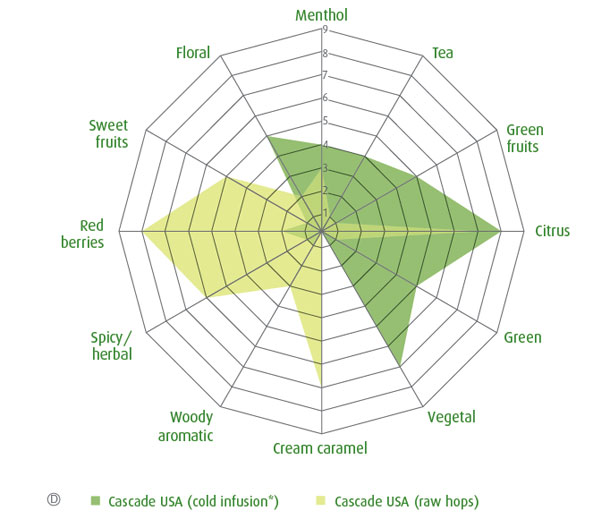

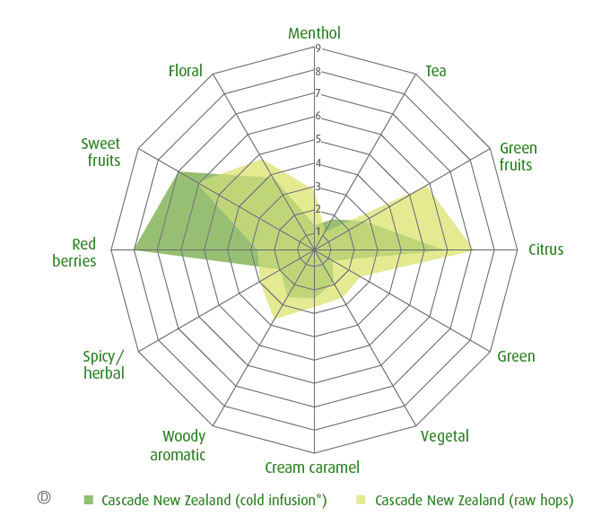

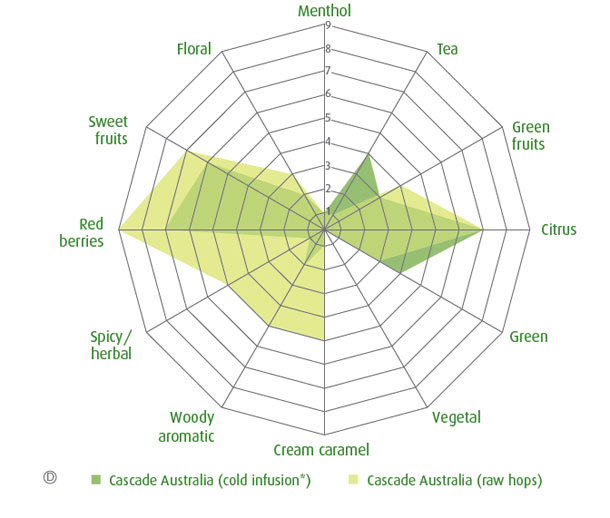

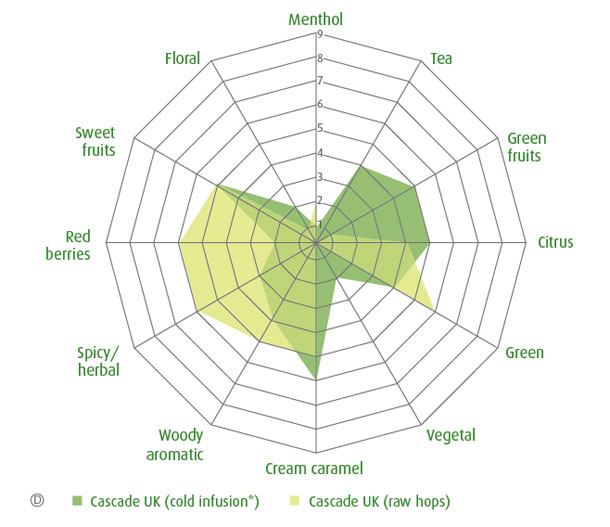

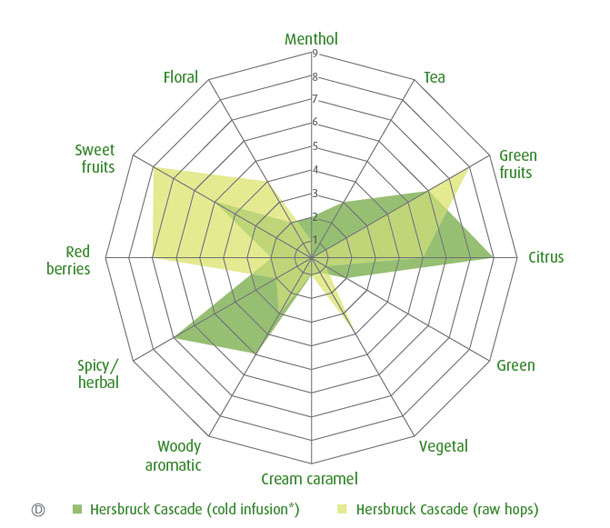

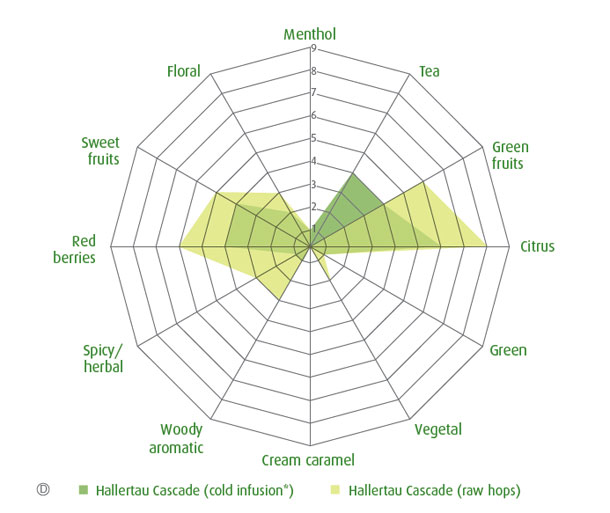

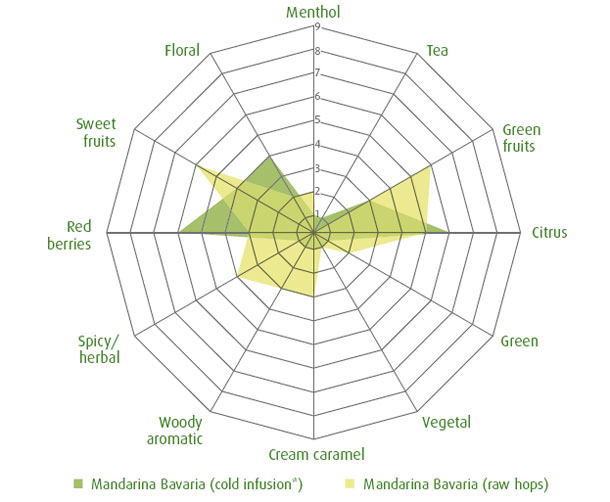

Cascade provides an excellent opportunity to explore these differences. German farmers recently began growing Cascade and in 2012 the Society for Hop Research released three new varieties, all of which were bred as children of Cascade. In addition, German hop merchant Barth Haas included Cascade grown at six locations in its three-volume “Hop Aroma Compendium.” Two beer sommeliers and a perfumist evaluated each of the hops “raw” and in a cold infusion. The infusion is intended to emulate dry hopping.

Mandarina Bavaria is pictured in the final spider graph. It is one of the varieties released in 2012 and already popular with American breweries (it is prominent in Firestone Walker’s Easy Jack). Like its mother, it is rich in geraniol. When it released Cascade as a new variety in 1972 the USDA did not have the instrumentation to measure geraniol, said Al Haunold, who was the hop geneticist at the time. Haunold has told the story many times about the role the Adolph Coors Company played in getting Cascade into the public domain.

He recently elaborated for an oral history kept at the Oregon Hops & Brewing Archives. Coors expected to be able to replace imported hops that it was using with Cascade. It didn’t work out as they expected. “The beer tasted OK, except when the beer drinker would have another bottle of beer … something would come up through the nose he wasn’t familiar with. We know now that it is geraniol.”

The European landrace hops that Coors had been using contain little to no geraniol — which on its own adds floral notes, think geranium, and can be rose-like; and of course may be transformed during fermentation.

By the late 1970s the USDA was able to analyze more components in hops (information readily available now, such as the percentage of myrcene or cohumulone), although it was be later before the lab could easily sort out linalool, geraniol and other compounds. It was in the late ’70s that Coors sent Hallertau hops to the lab to be analyzed because their finished beer had higher levels of bitterness than they expected.

“The first time I saw the cohmulone levels I thought, ‘This is Brewer’s Gold’ and sure enough it was,” Haunold said. Brewer’s Gold is a cross between a hop found growing wild in Canada and an unknown European landrace variety, so a mutt with America character and higher level of alpha acids than Hallertau Mittlefrüh, which Coors thought it was buying.

“The Germans didn’t really cheat,” Haunold explained. By law they were allowed to label any hop grown in the Hallertau region of Bavaria “Hallertau” and they had for centuries. After some negotiations they agreed to begin including the variety of hop, the year it was grown, and the region it was grown in on labels.

In the years since brewers have focused on varieties ahead of region. As Cascade illustrates, it is important to consider both.

*****

Thanks to Barth-Haas for permission to use the spider graphs.

The March/April edition of DRAFT magazine has a lovely little story about Tiah Edmunson-Morton and the Oregon Hops & Brewing Archives. (Full disclosure: I wrote it.)

The March/April edition of DRAFT magazine has a lovely little story about Tiah Edmunson-Morton and the Oregon Hops & Brewing Archives. (Full disclosure: I wrote it.)