The expanded hop acreage report released this week by Hop Growers of America indicates that acres strung for harvest in states outside the Pacific Northwest increased almost 58 percent between 2015 and 2016 to nearly 2,000 acres. And what does that mean?

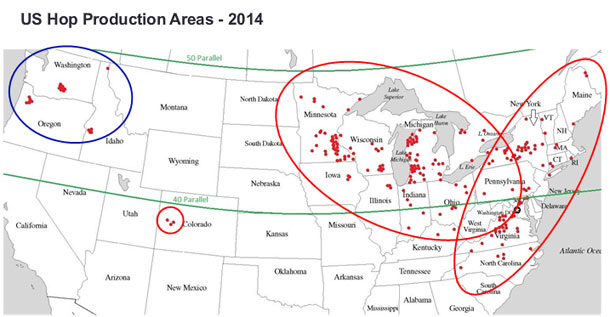

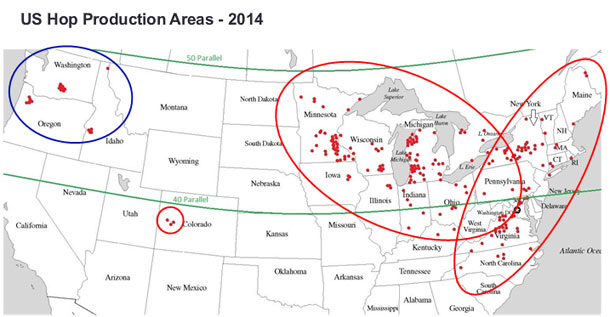

I pose this as a question I am not prepared to answer. I hauled out this map, which represents where hops were being grown in 2014, for my Zymurgy Live presentation last month. Look at it and you might think brewers in much of the country have access to locally grown hops. But in 2014 only 2 percent of planted acres were in those red circles. In 2015 the number increased to 2.8 percent and in 2016 to 3.7 percent.

Right now those acres are not nearly as productive as the ones inside the blue circle. It will be several years before we can measure how productive, or not, they are. If you look at the numbers you will see acres in Michigan doubled in 2016. Outside the Northwest it will be three years before a hop plant reaches maturity. Yields will be less until then, and of course less in years when growing conditions are not favorable. This is agriculture.

Right now it doesn’t look like most non-Northwest hop yards will manage yields equal to those in the Yakima Valley. So farmers in New York, Michigan and elsehwere will not be able to compete strictly on price. Can they in other ways? Steve Miller, hired by the Cornell Cooperative Extension in 2011 as the state’s first hop specialist, thinks so. “I think five years from now we’ll be in that (competitive) position,” he said last year. “(Brewers will say) this Fuggle or this Cascade is not just local. I actually like it better than I can get elsewhere.”

Another wild card is interest in neomexicanus varieties. So a bit of background. The genus Humulus likely originated in Mongolia at least six million years ago. A European type diverged from that Asian group more than one million years ago; a North American group migrated from the Asian continent approximately 500,000 years later. Although there are five botanical varieties of Humulus — H. lupulus (the European type, also found in Asia and Africa; later introduced to North America), H. cordifolius (found in Eastern Asia, Japan), H. lupuldoides (Eastern and north-central North America), H. pubescens (primarily Midwestern United States), and H. neomexicanus (Western North America) — the first and last are of interest to brewers.

Hops of American heritage, which include some grown in Australia and New Zealand (and now even England and Germany), contain compounds found only at trace levels in hops originating in England and on the European continent. Among them is a thiol called called 4-mercapto-4-methylpentan-2-one (otherwise referred to as 4MMP), a main contributor to the muscat grape/black currant character associated with American-bred hops such as Cascade, Simcoe, and Citra. It has a low odor threshold and occurs naturally in grapes, wine, green tea, and grapefruit juice. It is one contributor to what were described as “unhoppy” aromas not long ago and today as desirable “fruity, exotic flavors derived from hops.”

Interest in native American hops is twofold. First, they have had hundreds or thousands of years to adapt to their environment and develop resistance to local diseases. They may well be better suited to growing in new regions than varieties bred for the American Northwest. Second, they may contain compounds that yield new aromas and flavors

I mentioned Todd Bates’ breeding program and the “Frank Zappa hop” last month, but it is worth adding that varieties Eric Desmarais at CLS Farms chose not to grow are showing up elsewhere. The names to look for are Neo and Amalia. A story in Local Flavor magazine indicates Santa Fe Brewing bought the entire stock from CLS, but the rhizomes were previously available via mail order and got shipped to all sorts of locations.

At Homebrew Con week before last a homebrewer showed my a photo of his Neo plant climbing right up a wire attached to the roof of his house. That’s local.