Let’s cut right to the chase. Forget, at least for a moment, how Brother Thelonious pours, the various aromas that rise from the glass, the flavors, the finish. Instead go directly to the pairing: vinyl. Yep, serve this one with vintage jazz LPs (or even 78s).

Let’s cut right to the chase. Forget, at least for a moment, how Brother Thelonious pours, the various aromas that rise from the glass, the flavors, the finish. Instead go directly to the pairing: vinyl. Yep, serve this one with vintage jazz LPs (or even 78s).

North Coast Brewing in California wrote the recipe before giving this beer its name, so it wasn’t crafted with the idea it would be served in jazz clubs or that consumers at home might listen to Thelonious Monk or Monk compositions or jazz in general will sipping this strong dark Belgian-inspired ale.

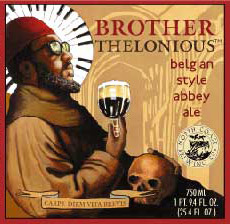

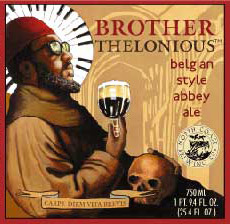

But now it has the name, the fabulous label with piano keys circling Monk’s head, and the context in which you might drink this beer has changed.

It was more than 10 years ago that Stephen Beaumont wrote a story for All About Beer magazine about matching musical styles to beer styles. In revisiting the idea in A Taste for Beer he admitted that this was at time “a bit of a stretch” before deciding “sometimes a particular tune cries out for a specific beer.”

That connection begins in the head of the drinker. For instance, Beaumont wrote “I paired the deeply spiritual sounds of Bob Marley’s Uprising Album with the equally pious and reflective flavor of Chimay Grande Reserve.” Instead I might point first to the multi-level layers that Marley and the Wailers create and that Chimay Blue somehow finds similar depth (or did in 1995).

But what if we think about beer as music?

Consider another recently released beer: Avant Garde, the first offering in the new Lost Abbey line from Port Brewing. After all, Monk was a trailblazer for the jazz avant-garde. Though inspired by biere de gardes first brewed in French farmhouse breweries, Avant Garde also blazes a bit of its own trail.

It delivers the toasty/bready aromas and flavors we expect in a biere de garde – including a haunting earthy element – in playful harmony. It also provides surprising spicy notes that grab your attention without raising the volume. Perhaps not as riveting as the back and forth between Monk and John Coltrane in a composition such as “Sweet and Lovely,” but drawing upon the same sort of tension.

For that reason you might not want to drink Avant Garde while listening to Monk. You could prefer a beer that asks for less attention. (Personally, given that Avant Garde makes an excellent pairing with a variety of dishes, deferring to other flavors when need be, I think it works well with something like “Monk’s Dream.”) Avant Garde speaks to you without raising its voice.

Back to Brother Thelonious. The label and name give the beer – it is being released in conjunction with the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz), and the brewery will make a contribution to the Institute for every case sold to support jazz education – a chance to speak to new customers. These are drinkers who may not usually order beer, and certainly some who wouldn’t consider a beer as bold, fruity (plums and raisins) and what many would call funky as a Belgian-inspired dark ale.

Brother T. is complex and challenging, though not nearly so much as a Monk composition. At 9% abv and packaged in a 750ml (wine-size) bottle, it’s a beer to sip and share – and probably one to stick in the cellar and see how it evolves.

As quickly as the dark fruits, some caramel and roasty flavors come upon you they are whisked away by a surprisingly dry finish. Sweetness and alcohol become a memory you can consider, or not – concentrating instead on the music (remember, that’s why we’re here).

This beer is a perfect example of why we shouldn’t assign numbers or try to rank beers. What’s inside the bottle is good enough, but there’s much more to Brother Thelonious.

In one of my various beer jobs I try to describe beers in about 75-80 words (each) for All About Beer Magazine’s Beer Talk. I’ve considered posting those “tasting notes” here but prefer the idea of drinking notes and providing more context. I’m still struggling with how to do that, and mention that only because I tasted Avant Garde for the next issue of AABM. Here I don’t have to limit myself to 75 words.

In one of my various beer jobs I try to describe beers in about 75-80 words (each) for All About Beer Magazine’s Beer Talk. I’ve considered posting those “tasting notes” here but prefer the idea of drinking notes and providing more context. I’m still struggling with how to do that, and mention that only because I tasted Avant Garde for the next issue of AABM. Here I don’t have to limit myself to 75 words. Let’s cut right to the chase. Forget, at least for a moment, how Brother Thelonious pours, the various aromas that rise from the glass, the flavors, the finish. Instead go directly to the pairing: vinyl. Yep, serve this one with vintage jazz LPs (or even 78s).

Let’s cut right to the chase. Forget, at least for a moment, how Brother Thelonious pours, the various aromas that rise from the glass, the flavors, the finish. Instead go directly to the pairing: vinyl. Yep, serve this one with vintage jazz LPs (or even 78s).