Imagine Iowa without corn, or Illinois without soybeans.

That’s what it would have been like in the 1870s to think of New York without hops. By 1879 New York grew 80 percent of American hops. Four years later, The Western Brewer provided an industry overview: “It will be seen that in 1850 hops were raised in 33 States and Territories; in 1860, in 37; in 1870 in 36; in 1880 but 18. … It remains to be seen whether California, Oregon, and Washington Territory will increase their production; or, in a few years, drop off as so many others have done. It is probable that New York will always remain the banner hop state.”

Instead, within 10 years the Pacific Coast produced more hops than New York, and by the time Prohibition began New York farmers grew less than 4 percent of the national crop. This happened for multiple reasons: lower yields in New York than on he West Coast, hop disease issues, higher labor costs, and small inefficient operations.

Hop Growers of America estimates New York farmers strung 250 acres of hops in 2015, two-thirds more than in 2014. That’s considerably less than the 39,072 acres in 1879, when 10,000 New York farmers harvested 21.6 million pounds, but the pace of expansion has picked up. The first commercial field to operate since 1954 was planted in 1999, but 11 years later farmers harvested only 15 acres.

“We have a real mix of people,” said Steve Miller, hired by the Cornell Cooperative Extension in 2011 as the state’s first hop specialist. “There are only a couple of growers who’ve had hops in for more than 10 years in the state. The vast majority of growers have only had them in for a year or two.”

Last year, Miller estimated there are now about 75 farmers there with two to five acres of hops, and most have the potential to expand. Yields on farms with mature plants have topped 1,500 pounds per acre. In 1879 the average was 554. “It’s based on people becoming growers, not hobbyists,” Miller said. “People who have knowledge and equipment and barns.”

The state of New ,supports this revival in a variety of ways, including funding Miller’s research. So has Brewery Ommegang outside of Cooperstown. From the time Ommegang opened in 1996 its press releases mentioned it is located in the former center of U.S. hop growing. This always seemed a bit curious, because at the time nobody in New York was growing hops and you wouldn’t describe any of Ommegang’s beers as hop focused. Although the brewery recently released its first IPA and brews a range of hop forward pale ales, hops still aren’t what you think of first when somebody says Ommegang.

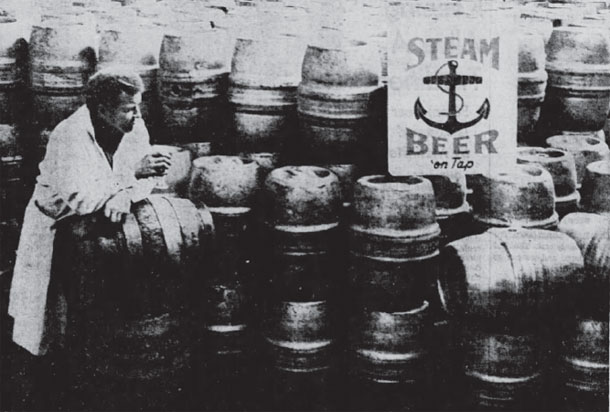

Ommegang posted the photo above last month, showing the small hop yard at the brewery. It is growing test varieties for the Cornell Extension program and will trial them in beers. The brewery also bought one and a half tons of New York hops last year. A good portion of those went into Hopstate NY, a pale ale released only in New York state a couple of weeks ago. It is brewed with Cascade, Nugget and Chinook hops, so it is brimming with citrus aroma and flavor, its resin character lingering beyond the finish.

No melon or blueberry or other exotic New New World aromas or flavors, but something different than New York hops offered in 1879.

A bit of disclosure: We don’t live in New York. I was able to taste the beer because the brewery sent me some. I certainly would buy it if I lived in New York. I won’t claim that at first sip, or third for fourth, that I thought, “Oh, this tastes of New York” (or the rolling hills around Coopertown, of which I am quite fond). But I could see it becoming a familar taste. One of place.

Last month when I was in California I had a lengthy — rambling, you might say — conversation with Brian Hunt at Monnlight Brewing about what makes a beer relevant. I’m going to be a while sorting that out, but I’m pretty sure than Hopstate NY is an example of relevant.

Pardon the length, but I’m posting the entirety of the email that Jester King Brewery sent out yesterday. Thoughts after the message.

Pardon the length, but I’m posting the entirety of the email that Jester King Brewery sent out yesterday. Thoughts after the message. Host Nathan Pierce has asked contributors to write about

Host Nathan Pierce has asked contributors to write about