Don’t expect me to answer that question. It was posed by Stonch at Lew Bryson’s Seen Through a Glass, and I started to comment there before I realized I was about to exceed a sensible length for comments.

The Brewers Association has a specific definition (scroll down on that page):

CRAFT BEER: Craft beers are produced with 100% barley or wheat malt or use other fermentable ingredients that enhance (rather than lighten) flavor. Craft beers only come from craft brewers.

And …

CRAFT BREWER: An American craft brewer is small, independent and traditional. Craft beer comes only from a craft brewer.

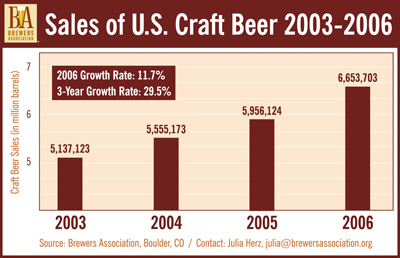

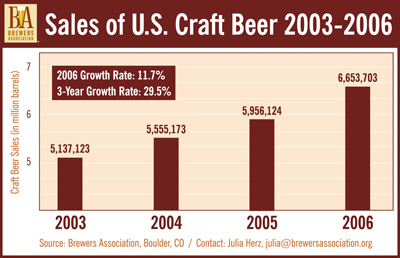

So when the Brewers Association collects data and reports 11.7% growth in 2006 over 2005 it isn’t including beers from Yuengling, all-malt beers from Anheuser-Busch, Blue Moon from Coors and many others.

Over time that’s made compiling and comparing numbers a little easier. For instance, had the BA (then the IBS) included Michelob Specialty beers in its calculations in the late 1990s then craft beer sales would have appeared to take a giant leap of (a guess) 800,000 barrels in 1997. We would have been comparing apples to oranges. The number is a guess because A-B never released figures for its specialty beers. In other words, the BA/IBS couldn’t have included them anyway.

Likewise, Coors does not report sales of Blue Moon Belgian White. Except in 2005, when they confirmed production of 200,000 barrels (more than the entire production of all but six craft breweries). They haven’t made a similar revelation this year, but I’ve heard from somebody – not at Coors, but who should know – that sales more than doubled to 500,000.

Just for fun, let’s plug that into the chart above, increasing both the 2005 and 2006 figures and then doing the math. Presto. Growth of more than 16%. Does that difference matter? Probably.

That’s the equivalent of nearly 7 million cases of Blue Moon that people are grabbing at the grocery store or convenient store, often from shelves where few craft beers land. If those drinkers are anything like everybody else who drinks craft beer – and remember these people (who may be you) are paying a premium price for Blue Moon, haven’t read the BA definition, and (poor fools) think it is craft beer – then they are going to try other beers that cost more and aren’t advertised on television.

This is not a new discussion. Fred Eckhardt wrote a great column on this subject 10 years ago in All About Beer magazine. He began with a definition from Vince Cottone written in 1986 (less confusing times, perhaps).

Cottone, the first to use the term, “craft brewer,” was implacably uncompromising in what he meant by that name. “Craft brewery,” he said, “describe(s) a small brewery using traditional methods and ingredients to produce a handcrafted, uncompromised beer that is marketed locally (and is) True Beer.” He also listed seven other small brewers as brewing “non-true” beers, including San Francisco’s Anchor (although a “craft brewery in spirit,” its beer was pasteurized), and six other small brewers who brewed malt extract beer. He had no patience whatever with “contract brewers.”

Eckhardt polled beer industry types in an effort to define “craft beer” and got answers that went beyond that. All of them are worth reading. For balance I suggest lingering words from Tom Schmidt of Anheuser-Busch:

I don’t believe there is anything such as “craft beer.” The use of the term may lead consumers to believe that beer made in some small, quaint place is much better than beer that is produced in a large, efficient brewery, where quality and consistency are the hallmarks. We all fight the same battle using the same raw materials. These supposedly “craft breweries” are finding that, to produce consistent products, they require process controls much the same as the larger breweries. Our brewmasters are (dedicated) “craftsmen,” not just brewing “engineers” who monitor the process from afar. Just because we are successful should not detract from the fact that we are also quality “craftsmen.”

But I confess that my favorite is from Greg Noonan of Vermont Pub & Brewery:

I wish that Vince Cottone had trademarked the term. (He would be) a good arbiter of what is and what isn’t “hand-made.” (He would reject) beers made in “micro-industrial” quarter-million barrel breweries and “fruit beers” made with 0.003 percent fruit-flavored extract. (If Congress were to legislate an appellation, the licensing board should include) Cottone, Carol Stoudt, Randy Reede and Teri Fahrendorf (to ensure) its integrity. Craft brewed (should) mean pure, natural beer brewed in a non-automated brewery of less than 50-barrel brew length, using traditional methods and premium, whole, natural ingredients, and no flavor-lessening adjuncts or extracts, additives or preservatives.

Yes, there are breweries using automation and producing beers I’d call “craft” with a brew length longer than 50 barrels, so feel free to quibble. But not with the spirit in which his definition was written.

With a nod toward Bill Maher’s “New Rules” as opposed to Miller’s Man Laws …

With a nod toward Bill Maher’s “New Rules” as opposed to Miller’s Man Laws …

If starts with Lew Bryson’s post

If starts with Lew Bryson’s post

There has been a fair amount of hand-wringing as the partnership of Fordham Brewing and Anheuser-Busch prepares to

There has been a fair amount of hand-wringing as the partnership of Fordham Brewing and Anheuser-Busch prepares to