A few post American Hop Convention thoughts, because I really should get back to research on the “not hops” book.

– @LoftusRanches unleashed a spectacular seven-minute tweet storm yesterday that illustrates how quickly farmers in the Northwest have recognized a shift in hop demand and adjusted. This is not simple or risk free. Land, new trellis systems, getting plants in the ground is only the beginning. Adding picking, drying and processing capacity is expensive. We’re talking multiple millions of dollars, every year for the next several years.

But, wait, isn’t worldwide beer production flat? Yes, but this isn’t a matter of selling different varieties of hops to a new set of brewers. The big guys over there brew 3 million less barrels and the new guys here make 3 million more. Different varieties, but the same land and processing equipment. That’s because the members of the Brewers Association and breweries, in the United States and elsewhere, that makes similar beers don’t use hops like the ones brewing pale colored, lightly hopped beers.

It is not as simple as this math, but the conclusion would be the same if we used more precise numbers. Alex Barth, president of hop merchant John I. Haas, showed a chart that illustrated how hop usages has shrunk for more than a century. Brewers worldwide use about .15 pounds of hops per barrel. Chris Swersey of the Brewers Association showed one that indicated members surveyed used 1.43 pounds per barrel in 2014 (steadily growing since the rate was .95 in 2008).

So if BA members brew 3 million additional barrels in a year, and they came close to that in 2014, they might use 4.3 million more pounds of hops. Considering the yield of the varieties they want that takes almost 2,400 acres of land. The guys making lightly hopped beers actually brew them with varieties that yield more per acre. So not only might they need only 450,000 pounds of hops to brew 3 million barrels, but those hops could be grown on about 200 acres. Even rounding down we are talking about more than a 2,000-acre difference.

Swersey and BA economist Bart Watson have done the calculations on what quantities of raw materials association members will need if they are to reach the BA’s goal of selling 20% of the beers brewed in the U.S. by 2020. American brewers used about 22 million pounds of hops in 2014. They’ll need 50 million if they are to reach their goal in 2020.

That’s a lot of acres.

– To give you an idea of the speed with which farmers in Washington, Oregon and Idaho have reorganized their hop portfolios:

* Cascade production has basically doubled in three years.

* Centennial production has almost doubled in three years.

* Citra production is up 3.75 fold in three years.

* Simcoe production almost doubled in three years.

* This was Year 2 for Mosaic and production already reached almost 1.5 million pounds. It took Centennial 23 years (until 2012) to reach that level.

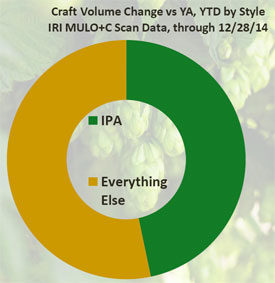

– Farmers in the Northwest and in Germany grow 75 percent of the hops in the world, and that’s not changing. They are good at it. Plus they are growing the varieties popular in hop-forward beers, and Watson showed this slide as a reminder of how important beers with IPA in their names are to sales.

– Farmers in the Northwest and in Germany grow 75 percent of the hops in the world, and that’s not changing. They are good at it. Plus they are growing the varieties popular in hop-forward beers, and Watson showed this slide as a reminder of how important beers with IPA in their names are to sales.

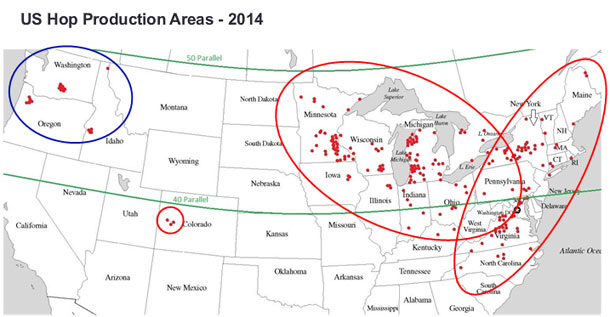

However, what’s going in across the country is dang interesting. Just 71 farming entities (those may include multiple farms) in the Northwest produced about 71 million pounds of hops last year, and they will grow about 10% additional acres this year. Hundreds of farmers across the rest of the country grew hops on roughly 1,000 acres, producing less than a million pounds.

What is their impact going to be? I haven’t found anybody to answer that question. If they are successful then they may solve a part of the acre problem. They’ve certainly drawn more attention to hops. It seems like every time a farmer in Kentucky or North Carolina or Maine plants hops it merits a story in the local paper. It reminds me of 20 years ago when brewpubs were a novelty. You’d walk into a new place and there would be a wall full of newspaper stories about it. That really hasn’t changed much. Newspaper people like to write about beer.

First there is the matter of growing the hops. Then there is the rest. “I get these calls every day (from would be hop growers),” said Sean McGree, hops manager at Brewers Supply Group, whose office is located in the Yakima Valley. “All they are worried about is getting their trellises in and hop going. They don’t realize that 60 percent of the quality that brewers see comes after the hops are picked.”

They’ve still got to be able to distribute (sell) what they grow. That infrastructure is a work in progress. Spencer Gray of Sugar Creek Hops in Indiana was part of the “Opportunities for family farms and smaller marketing operations” panels at the hop convention. His family planted five acres this year and to plans to sell hops from around the world as well as their own. “I saw an underserved market. The industry is so centralized,” he said. His plans are ambitious, including establishing a breeding program that incorporates native American hops, and he expects Sugar Creek will begin processing (pelletizing) hops for the next harvest.

Gray’s is one of dozens of interesting stories. For instance, several New York farms are marketing some of their hops as heirloom varieties that have a direct link to the nineteenth century. Pedersen Farms simply calls its own, “New York.” (I’m still waiting for a Double IPA called New York, New York.) Others are growing found varieties, natural crosses between hops imported from Europe up to 400 years ago and native American hops. “It’s like finding wild apples,” said Steve Miller of Cornell Cooperative Extension services. “A majority are so-so.”

Stay tuned.

*****

Map at top courtesy of John I. Haas, Inc.

You might want to trademark “New York, New York” before one of the breweries does.

Where are all the hops going to be grown can also be a function of what hop can grow where. 😉