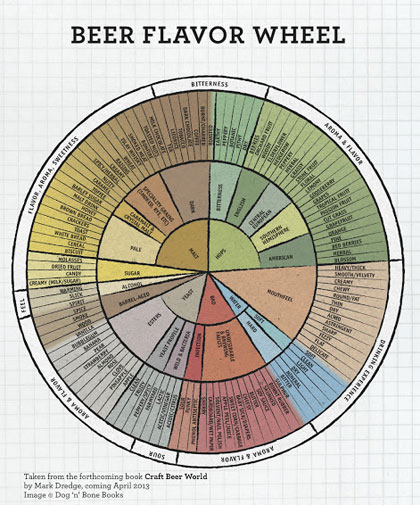

Mark Dredge posted this new Beer Flavor Wheel today at Pencil and Spoon. (If you click on the image you’ll head over to his blog, where the wheel is a bit larger).

This is a much more drinker friendly wheel than the traditional one, created for Dredge’s new book, Craft Beer World, which just went to the printer. As mentioned here before, the beer flavor wheel was developed in the 1970s by the Master Brewers Association of the Americas and the American Society of Brewing Chemists following the lead of Danish flavor chemist Morten Meilgaard. It was one of the first such wheels. A wine aroma wheel came later, as did the Flavour Wheel for Maple Products, a South African brandy wheel, and a variety of other fun dials.

The Beer Wheel was not designed for consumers but to provide reference compounds that can be added to beer samples to represent the intended flavors. It continues to grow in size, and there is every possibility that the committees working on its redesign will settle on several subwheels.

Also mentioned here, and pictured in For the Love of Hops

the Hochschule RheinMain University of Applied Science created a Beer Aroma Wheel (actually two wheels) with the goal of providing terms more suitable for communicating with consumers and focusing less on defects.

Panelists who helped develop the terminology used aromas of fruits, spices, everyday materials, and other foodstuffs to describe their sensory impression. Because there is the rare occasion where 4-vinyl guaiacol is appropriate in conversation, but rare remains the best adjective. Clove works much better in mixed company (geeks and non geeks).

OK, not necessarily something you want to do in public. But both a good way to learn a little more about the beer you are drinking and your own senses.

OK, not necessarily something you want to do in public. But both a good way to learn a little more about the beer you are drinking and your own senses.