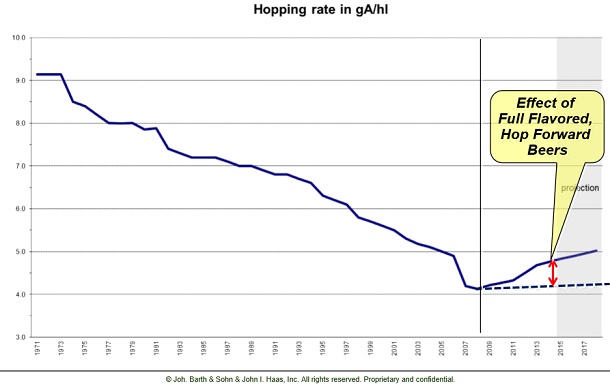

This chart is actually one that Alex Barth, president of John I. Haas, showed at the 2015 American Hop Convention. It’s relevant right now because today the Barth-Haas Group released its annual hop report. And it confirms the projection Alex Haas made 18 months ago.

The chart tracks hop usage since 1971. One hundred years ago brewers used the equivalent of 12.6 grams of alpha acids per hectoliter (26.4 gallons or 85% of a barrel). That had fallen to 9.1 grams in 1971 and continued to drop regularly until it was just over 4 grams in 2011. It ticked up to 4.5 grams in 2011 and will reach 5.4 this year.

This doesn’t mean that beers are getting more bitter. It means that brewers are using hop differently and using more of them.

Because of heightened interest in hops much of what is in the report has already been reported. The archives are invaluable if you want to look up how much Strisselspalt the French grew 20 years ago, or if the hop called Record (which is in this year’s Sierra Nevada Oktoberfest) was ever very popular, or what spot prices were in any particular year.

This year’s report begins with a discussion of “How hops have changed the world of beer, and vice versa…”

The central task of hop research used to be “quite simple.” The breeding of new hop varieties focused on yield, alpha acid content and resistance to diseases and pests. This met most of the requirements of both the hop and brewing industry. When, after many years, a new hop variety was finally licensed, the brewing industry accepted it and brewed its beers with it – mostly with success. This went on for years – until a completely new generation of brewers grew up in the United States. More and more breweries were built and more and more people took an interest in brewing beer – not only on a small scale for their own consumption, but also on a large scale for sale to others. Suddenly, hop aroma acquired a totally new standing. The craft brewers had taken a fancy to the aroma varieties in particular. Gradually, they developed their own ideas, philosophies, techniques and innovations with regard to brewing which have meanwhile found their way into the world at large. … At the same time, there arose a growing desire for unusual hop aromas, and within a relatively short period of time new hop varieties with a wide range of flavours appeared.”

That’s why, by their count, in 2012 the number of hop varieties worldwide stood at 180; today there are 250 varieties. That doesn’t include hops been reconsidered when they grow in different regions. For instance, Gorst Valley Hops has renamed Chinook, calling it Skyrocket, because in Wisconsin the hop is less piney and resinous and smells more tropical. And in New Zealand the new name for Cascade is “Taiheke.”

Of course, the most popular varieties are driving growth.

| Variety | 2011 | 2015 | Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cascade | 1,002 | 2,748 | 174% |

| Centennial | 308 | 1,807 | 487% |

| Simcoe | 200 | 1,338 | 569% |

| Citra | 97 | 1,211 | 1148% |

| Amarillo | 185 | 683 | 269% |

| Crystal | 54 | 245 | 354% |

The acreage here is measured in hectares (I know, maybe it should be called hectarage), and there are 2.47 acres to a hectare. A couple of varieties not in the chart because acreage was not reported in 2011: Mosaic 36 ha in 2012 and 728 in 2015; and El Dorado 39 in 2013 and 181 in 2015.

H*ll yes it means (craft) beer is getting more bitter. The recent “hop everything at all costs” is ruining a lot of otherwise good beer for the many people like me that aren’t hopheads.

Some hops = goodness

Hops for the sake of more hops = not

Thanks for you comment. I will spare you deadly details about alpha acids, isomerized alpha acids, bitterness and efficiency/inefficiency. And I agree that there are plenty of bitter beers out there. But as Barth-Haas had documented the amount of hops used (as measure by alpha acids) has increased but not the level of iso alpha acids (which produce bitterness).

Is it legal to rename a hop? I thought they were patented.

Some hops are patented and/or trademarked. Can’t mess with them. However it is OK to rename public varieties, most of which came out of government-funded breeding programs (but also include hops like Cluster). That’s what they’d done at Rogue Farms.