Note: Boak & Bailey periodically invite bloggers to post something longer than usual. This is my contribution.

*****

Conducting a study during the 2010 hop harvest in the Willamette Valley, researchers at Oregon State University’s Shellhammer Lab discovered something outside of the focus of the trials.

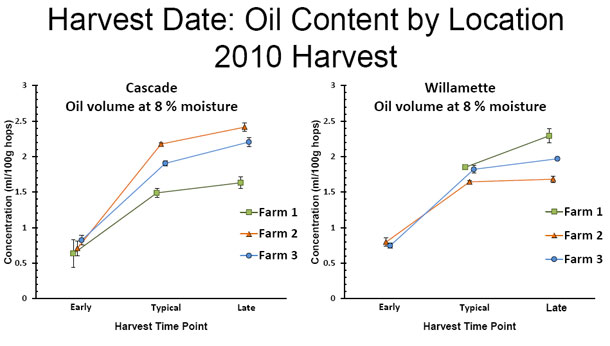

As well as learning about the impact harvest date has on hop oil content — considerable and important — they saw that concentration of essential oils varied in a way that did not suggest a single one of three farms involved was “best” for growing hops. Instead, the variety Cascade had a larger volume of oil at one location (Farm 2 in the illustration below) and the variety Willamette at another (Farm 1).

Hop farmers long ago learned that hops well suited to one region might not do as well in another. Refugees from Flanders established England’s first modern hop gardens relatively early in the sixteenth century, planting Flemish Red Bine hops. They did not produce desirable lupulin or much of it in English soil. Brewers likewise determined that the aromas of particular varieties were more to their liking from certain regions. So the research at OSU substantiates some of what is intuitive. Watermelons grow better some places than others, as do roses, basil, and carrots. Oh, and grapes. The variations are at the heart of what winemakers call terroir.

The significant difference in oil content on farms located just miles apart has wider implications. Most of the hundreds of odor compounds hops produce come from the essential oils. They further interact with yeast, the biotransformations creating still more odor compounds. The compounds, in turn, are responsible for aroma, and what constitutes desirable aromas in beer has broadened considerably in the past 40 years.

Hop scientists and brewers still have much to sort out, and more oil itself doesn’t guarantee anything. Cracking the code on how the composition of oils in a hop such as Citra or in one like Saaz impacts odor compounds will allow brewers to fine tune the way they use varieties, or more accurately a combination of varieties, to create beers that have currently fashionable flavors and aromas.

For example, research supported by Japanese brewer Sapporo has examined how geraniol metabolism might add to citrus and related flavors in beer. In one experiment, a team headed by Kiyoshi Takoi brewed two beers, using Citra hops in one and coriander seeds in the other because both are rich in geraniol and linalool. The finished Citra beer contained not only linalool and geraniol but also citronellol, which had been converted from geraniol during fermentation. The same transformation from geraniol into citronellol (perceived as rose-like, lime, other citrus, or peach) occurred during fermentation of the beer made with coriander.

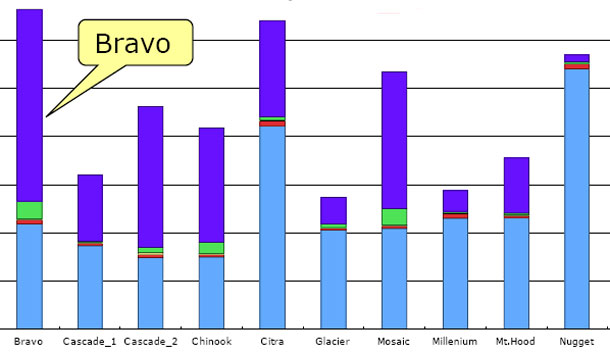

The scientists at Sapporo followed up with an investigation into the behavior of geraniol and citronellol under various hopping conditions and with various blends of hops. They identified several hops of American heritage rich in geraniol. They also looked for varieties with an excess of linalool. Some of those are shown here.

(Light blue is linalool, red is terpineol, yellow citronellol, green nerol, and dark blue geraniol)

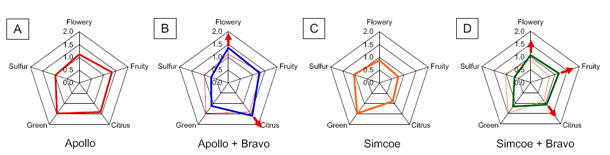

Bravo is highlighted because of its high geraniol content and because in the study Bravo was blended with Apollo in one test and Simcoe in another. A test panel described the beers blended with Bravo to be more flowery, fruity and citrus-like than the unblended beers.

Cascade, Chinook, Citra and Mosaic are all rich in geraniol, but notice that the two Cascade samples are different. They both came from Washington’s Yakima Valley. The differences are no doubt larger, at least on average, between Cascade grown in Yakima and Cascade from Oregon or Idaho. And what about from New York, Minnesota, Michigan and all the other states where farmers recently began growing hops? Or from New Zealand, Germany, Brazil and England?

Some of the differences are for the same environmental reasons grapes grown in the Napa Valley are more highly valued than those from Missouri, but with hops latitude is particularly important. Researchers realized only early in the twentieth century that day length controlled flowering plants, describing them as “photoperiodic.” While plants will grow between latitudes 30º and 52º, they thrive between 45º and 50º.

In 1983, the International Hop Growers Convention conducted a study that illustrated the importance of growing cultivars with day length requirements suited to where they are planted. In the trial cultivars with a common female parent that had been bred and selected in England, Germany, or Yugoslavia, at latitudes of 51°, 48°, and 46°, respectively, were all grown in those three countries, and also in France at 47°. The cultivars flowered earliest in the lower latitudes, the difference between Yugoslavia and England being 10 to 14 days. The English and Yugoslav plants both showed a steady reduction in yield as the sites became more remote from their place of origin.

Differences such as the ones the Shellhammer lab discovered illustrate latitude isn’t the only determining factor in why the hop grown here isn’t quite like the one grown there. John Henning, the research plant geneticist at the United State Department of Agriculture offices in Oregon, explained that environment and epigenetics combine to make hops from a particular area unique. All plant species have methylated DNA, which causes some genes to be “switched on” more easily than others. Differences in soil, temperatures, amount of rainfall, and terrain all may influence the methylation process. The underlying DNA does not change, but the methylation pattern can be different.

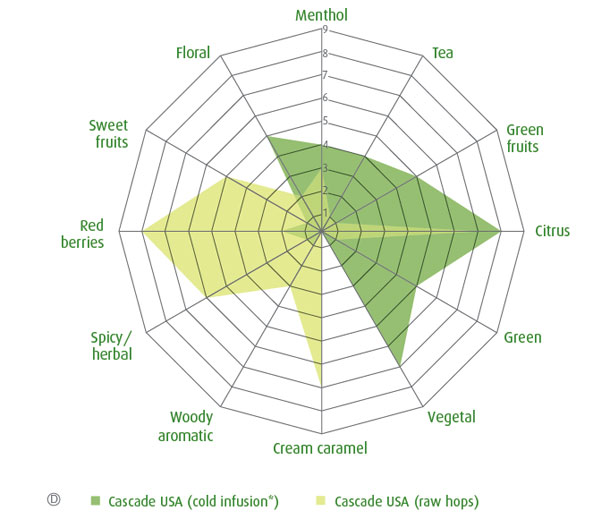

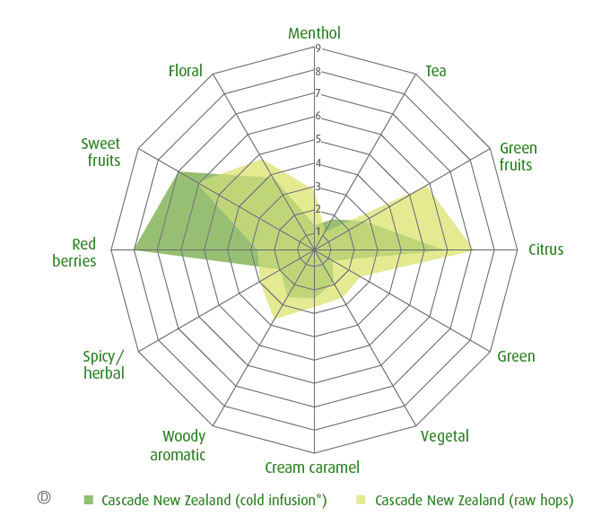

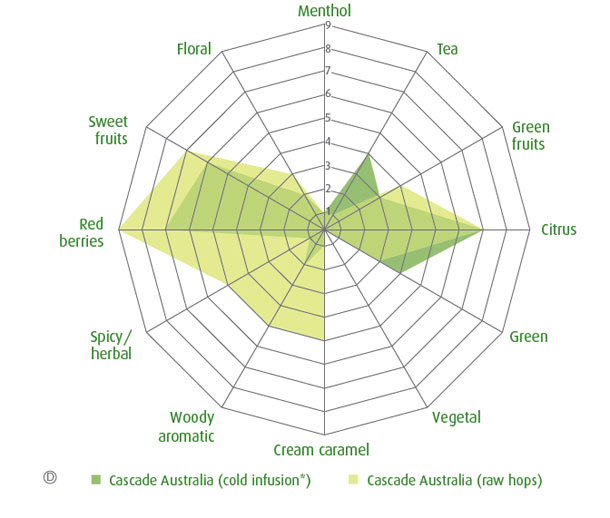

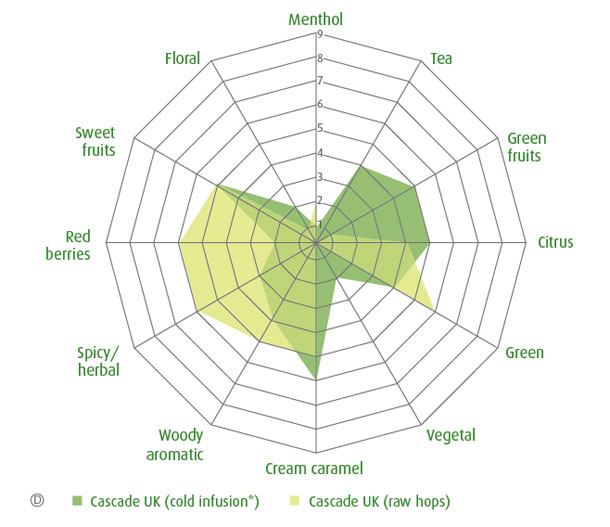

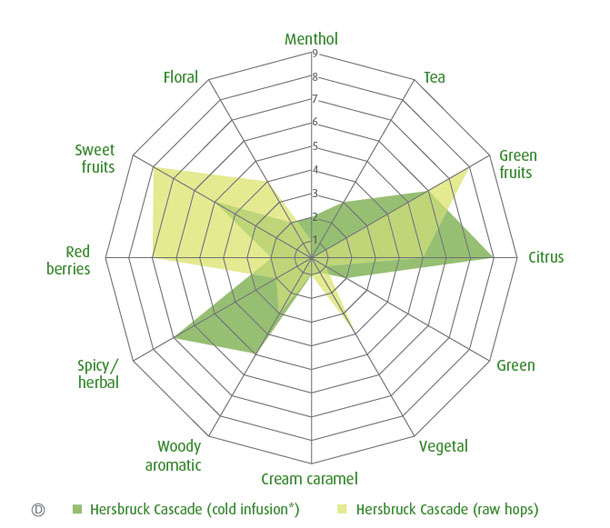

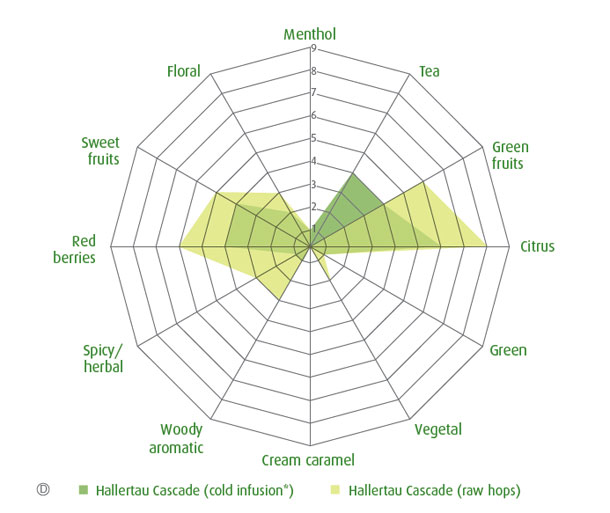

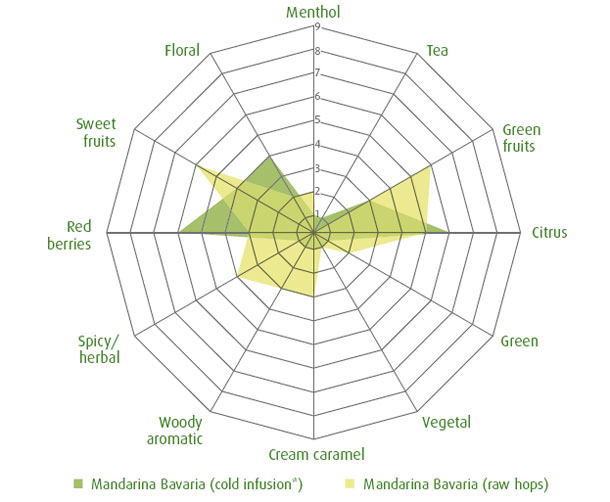

Cascade provides an excellent opportunity to explore these differences. German farmers recently began growing Cascade and in 2012 the Society for Hop Research released three new varieties, all of which were bred as children of Cascade. In addition, German hop merchant Barth Haas included Cascade grown at six locations in its three-volume “Hop Aroma Compendium.” Two beer sommeliers and a perfumist evaluated each of the hops “raw” and in a cold infusion. The infusion is intended to emulate dry hopping.

Mandarina Bavaria is pictured in the final spider graph. It is one of the varieties released in 2012 and already popular with American breweries (it is prominent in Firestone Walker’s Easy Jack). Like its mother, it is rich in geraniol. When it released Cascade as a new variety in 1972 the USDA did not have the instrumentation to measure geraniol, said Al Haunold, who was the hop geneticist at the time. Haunold has told the story many times about the role the Adolph Coors Company played in getting Cascade into the public domain.

He recently elaborated for an oral history kept at the Oregon Hops & Brewing Archives. Coors expected to be able to replace imported hops that it was using with Cascade. It didn’t work out as they expected. “The beer tasted OK, except when the beer drinker would have another bottle of beer … something would come up through the nose he wasn’t familiar with. We know now that it is geraniol.”

The European landrace hops that Coors had been using contain little to no geraniol — which on its own adds floral notes, think geranium, and can be rose-like; and of course may be transformed during fermentation.

By the late 1970s the USDA was able to analyze more components in hops (information readily available now, such as the percentage of myrcene or cohumulone), although it was be later before the lab could easily sort out linalool, geraniol and other compounds. It was in the late ’70s that Coors sent Hallertau hops to the lab to be analyzed because their finished beer had higher levels of bitterness than they expected.

“The first time I saw the cohmulone levels I thought, ‘This is Brewer’s Gold’ and sure enough it was,” Haunold said. Brewer’s Gold is a cross between a hop found growing wild in Canada and an unknown European landrace variety, so a mutt with America character and higher level of alpha acids than Hallertau Mittlefrüh, which Coors thought it was buying.

“The Germans didn’t really cheat,” Haunold explained. By law they were allowed to label any hop grown in the Hallertau region of Bavaria “Hallertau” and they had for centuries. After some negotiations they agreed to begin including the variety of hop, the year it was grown, and the region it was grown in on labels.

In the years since brewers have focused on varieties ahead of region. As Cascade illustrates, it is important to consider both.

*****

Thanks to Barth-Haas for permission to use the spider graphs.

I am thrilled in these days of declining quality in forms of beer writing that you do this, Stan, but I still do not understand why I can be delighted with the subtle and not so subtle differences with Rieslings grown on various patches of land, even various bits of my nearby Prince Edward county where I have traced the various loams from a 1948 Dept of Agricuture map and laced out in my mind where the recent vineyards have been planted.

But I cannot transfer the same experience to hops. Is it because hops join other ingredients and then enter into the fermenting process so that the effect gets diminished by the many more interactions? I fully appreciate that it may be me, that I sm more sensitive to the fluctuations in the chemistry of Reislong than hop. In any event, this is excellent as you have made the path you are walking down much clearer to me than I have understood it before.

Thanks for the kind words, Alan. First I think of the New World vs. Old Word terroir blah-blah-blah debates of wine, where the discussion is about allowing the grapes from a particular location to express themselves. Or if winemakers should manipulate everything because it is what some mythical drinker wants.

The beer world is equally uninteresting if everybody is trying to make the exact same beer.

Yes, the interaction of all the ingredients makes beer different than wine. But, and of course I’ve been accused of viewing these things through rose-colored glasses, you hope that the brewer understands the subtle differences in all the ingredients and plays to those when making a particular beer.

Very interesting, but while I get that in 1972 there was no technique in place to measure geraniol, what amazes me is that anyone could have thought 56103 really resembled Hallertau Mitterfruh. One would think basic sensory reports – smell and taste – would have shown how different it was, however the amounts used in early test brews may not have been enough to signal the difference.

This, combined with the inability of the lab to detect geraniol at the time, meant there was a likening on paper that didn’t exist in practise. However, as Al Haunold noted, by the second glass drinkers noticed what it was.

Haunold (in the link you gave) doesn’t mention grapefruit but that has always been the hallmark of Cascade whenever I’ve experienced its full effects, and this over 30 years and presumably from different crops and regions in the PNW. (I won’t say Europe, I’d think some modification of that characteristic may occur in such a distant and different growing area).

Of course as we know the story ends very well since Cascade helped kickstart the craft beer revolution. Al Haunold is a legend as far as I’m concerned and I would love to read a detailed interview with him about this history. I’d also like to know whether he considers the C hops and other new hops developed since ’72 fundamentally different from Cluster, neo-Mexicanus and other North American hops which preceded it or not. What the European brewers didn’t like about American hops in the 1800’s and mid-1900’s was a piney and blackcurrant (funky, probably what is considered dank today) character. Yet many of the post-’71 hops have this character.

Are the new American hops really just a development, due to the soils and climate in the U.S. especially the PNW, of what came before? Or are they something very new?

Whatever the answer, the keynotes of the hops which powered the craft brewing revolution are obviously distant in character from Noble hops. This is why I always smile when I read that Cascade’s origins lie in a plan to replicate the best qualities of a German Noble hop.

Gary

Stan, I see now that your link to the Oregon Hops and Brewing Archive actually contains a lengthy oral interview with Al Haunold. I find it difficult to hear due to the sound quality of the tape but will endeavour to work through it. Thanks, and for this interesting article.

Gary

The sound quality gets better after the opening, although it comes and goes.

Wonderful piece, Stan. But the more you talk about hops, the more I think “terroir.” You’re now producing evidence that suggests hops are even more sensitive than grapes to the conditions that constitute terroir. Maybe it’s just the word that you dislike. Everything else makes it sound like a profound effect.

And for that reason, I look forward to a decade or two from now, when we have hops growing all over the continent for comparison.

Jeff – You’ll notice I used the word terroir without whining. I’d still like to find another – and certainly have been thinking about it related to the indigenous book – because as Jamie Goode once wrote, within the context of wine, the concept of terroir “is blindingly obvious and hotly controversial.”

I did notice that! I sensed a shift in the universe.

I wonder if it’s hotly controversial in wine because evidence is so slender? That just doesn’t seem to be the case with hops, though.

Interesting. Confirms some of the confounding problems as a homebrewer buying hops from various providers and getting wildly differing results. There has even been a lot of discussion on the interwebs about early and late harvesting times and their impact on specific flavor profile expression, especially those that have a bit of sulfur, garlic or onion that present strongly. Makes me afraid that ‘vintage’ will be rolled out soon to market 2 year old Simco or Citra, and charge a premium.

I imagine those inconsistencies are amplified when buying hops by the box or buy the ton.

Given the demand for Simcoe and Citra I don’t think there will be much “vintage” around. But mentioning those two touches upon another topic. There is a certain amount of complaining about proprietary varieties. Because those are grown under license and closely monitored their consistency is much higher.

Harvest dates become more of a challenge as brewers flock to the same varieties, which tend to “should” be picked and processed within the same windows. Plenty of challenges the next few years meeting the demand for the hops currently in vogue.

That does not match my experience. Amarillo, in particular, seems wildly variable. But I suspect there’s more to this issue than meets the eye.

I should have been a little more careful with the way I worded that. i was referring specifically to Simcoe and Citra, 2014 crop

Could this be the latest way to differentiate a beer from it’s competition, with a cost premium of course?

As I suggested in replying to Alan, a brewer can choose to accentuate what it unique in a hop or blend it in with a bouquet of aromas and flavors. I don’t know that this has to come at a premium – in fact maybe it happens at a lower price point. Can’t get a particular expensive popular hop? Brew something different with a local and/or less expensive variety.

Wonderful, Stan. I still recall getting your book before a cross-country flight a couple years ago and slowly pacing myself through it. I dare say it changed the way I wanted to think and write about beer. I appreciate you sharing this work, which continues to resonate with me, especially in the context of added time and additional knowledge laid out in this post.

You, Jeff and others here continue to be an inspiration.

You embarrass me, Bryan, but thank you very much. Just don’t think it means you get preferential treatment when it comes to making the Monday links.

There are just too many variables to track terroir in this respect. The mix of hops used. Length of boil. Dry-hopping or use of hop jack if any. Age of hops. Pellets vs. hops vs. extract. The way the hops work with the selection of malts used. The yeast.

Possibly under very controlled conditions one can make certain determinations but in practice this will rarely occur.

I can see it more with wine which is a much simpler drink to make.

The alchemy of brewing resists this kind of analysis except I think for brewers themselves, to enable them to achieve more certain and consistent results.

Gary