Does this illustration courtesy of DRAFT magazine1 make you think about beer aroma and flavor any differently? Particularly hops? The point is not whether you find grapefruit more prominent in New Belgium’s Ranger IPA or Dogfish Head 60 Minute IPA or if you agree that Anderson Valley Hop Ottin’ IPA has more bitterness than Bell’s Two-Hearted Ale but less hop punch.

I like it because the colored meters make it easy to think in terms of volume (synonym: impact) as well as the way the aroma components fit together. This is different than spider graphs (here are a couple more examples beyond the one that follows), so brilliant that I take back everything nasty I said when DRAFT used the antiquated tongue map as an illustration in its early issues.

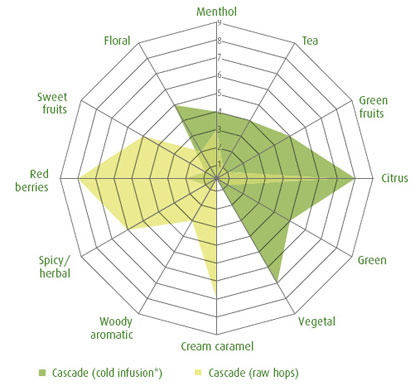

This spider chart appears in The Hop Aroma Compendium compiled by Joh. Barth & Sohn. The tan portion indicates how two beer sommeliers and a perfumist perceived the aroma of raw Cascade hops, while the green shows how that changed in a cold infusion (similar to dry hopping).

These work best if you are willing to accept, perhaps even embrace, a certain amount of ambiguity. Members of tasting panels at breweries are trained to identify X or Y as this or that aroma or flavor. That’s so their brewers can make beer with a certain level of consistency. (See New Beer Rule #4.) Drinking, and enjoying, beer can be altogether different, and it might be best not to get too specific when trying to pick out particular aromas or flavors. In How to Love Wine author Eric Asimov devotes an entire chapter to “The Tyranny of the Tasting Note.” It’s a topic he’s addressed before, and tends to get wine writers pretty riled up. He makes excellent points, but also some I’m not sure I agree with. Probably something better examined in a separate post (maybe even the next one). But a key takeaway is that when somebody starts describing “aromas of apricot, jam, guava, and jackfruit” that there’s little chance another drinker will get then that tasting note is not only useless, but discouraging.

These visual representations are much friendlier. Both managing editor Jessica Daynor and beer editor Chris Staten provided details via email about the illustration in DRAFT.

“. . . there’s no formal data behind the sensory ratings — just our ratings of each flavor element from 1 to 5 (that number was multiplied by 6 in design, which is how we got the final artwork you see in print),” Daynor wrote. “We feel that part of our job as editors is to present beer to readers in as many digestible ways as possible, and particularly for people new to beer, sometimes, it’s more practical to make sense of flavor elements visually, which is what we did here. It’s so easy to make generalized statements about IPAs: ‘They’re really bitter;’ ‘They’re hoppy;’ etc., but what does that actually mean? And if that’s the case, then aren’t all IPAs the same? With that piece, we’re trying to show that even among the most common IPAs on shelves, there are many flavor nuances that make each beer unique.”

Staten added: “I’ve always been intrigued with the path beer drinkers take when they’re first exploring the world of hops. Often, I run into newer drinkers who say they love IPAs but can’t figure out why particular IPAs rub them the wrong way — lot’s of the time it’s because they aren’t focusing enough on the flavor profile to discover likes and dislikes. The piece was just a casual way to let these particular readers know that there’s a wide range of hop flavors, and a wide range of flavor combinations/perceived bitterness/etc. from IPA to IPA.”

A casual way. I like that.

*****

1 The November/December issue (“Top 25 Beers of the Year” cover).

Fair enough, but what is cream caramel and what does it have to do with Cascade (or any) hops?

The fuller explanation: “Cream caramel includes butter, chocolat, yoghurt, gingebread, honey, cream, caramel, toffee, coffee.”

No, I don’t know how they got any of that in Cascade.

Not a factor in many American hops for them, though big in Millennium.

I don’t understand. Are you suggesting normal people do not benefit by seeking out the ordinary language of taste by asking those with them if they get some apricot in the taste just at that point right there? Talking it out works pretty well as long as no one plays evil overlord, admittedly a problem with beer nerds.

Besides, that isn’t a visual representation. This is a visual representation.

One thing I’ve enjoyed about Asimov’s writing is the emphasis he puts on context. I agree with you that within certain contexts noting particular flavors has value. On the other hand, at the store I’m thinking “Tonight I think I’ll go for a beer with more apricot than grapefruit.”

I hear you but, you know, I actually do go in a beer store and think I want a beer with more apricot than grapefruit. More likely I would say I want a date malty beer than an apple malty beer but I would never think in terms of varieties of hop or malt so much as their flavours.

What is “hop punch”?

And for Deviant Dale’s it says “Pine … Hop Punch”, what is between those two?

I do like the graphical interpretation of the flavors. Certainly makes comparisons easier. Do other styles get more flavor bars? (I’m also wondering to myself, are more then two flavor bars needed?)

Dave – It’s not my chart, but to me hop punch is hop impact, and certainly can be different than bitterness.

An example would be Boulevard’s 80-Acre Hoppy Wheat Beer, with 20 bitterness units.

I suspect if you held your nose (to keep from getting the aroma but also retronasal perception) you’d consider the bitterness much the same as Fat Tire (19 IBUs) or Blue Moon White (18). But when leave your nose open and everything changes.

On the Deviant that “onion” in the third slot.

I thought it said onion, but couldn’t remember any onion when having Deviant… nor have I read many beer reviews with the mention of onion.

Thanks for the description of hop punch.

You’re more like to get garlic and onion when you rub raw hops, with Summit pretty much being the poster child. But – and this is both one of the attractions of hops, but can make brewers crazy –

how prominent that certainly varies from year to year, but also from field to field, and from picking date to picking date.

I know a brewer particularly sensitive to onion/garlic who a few years ago kept his Amarillo pellets in plastic bins and shook them regularly so that some of that character was oxydized.

Much of that character will be lost during boiling, but it remains (and can be prominent) in dry-hopped beers.

I think I’m repeating myself on a similar post a while back! I like tasting notes that give food descriptors for taste and aroma — when i drank decent wine, I generally got what the reviewer was trying to get across. Yes, sometimes, it veers into parody. But it is difficult to get fleeting sense information into words: if its visual art, it’s a bit easier because others can confirm it should they see the work in question. Performing art becomes more difficult, because different performances are different performances. Pure music is more difficult still, and gastronomy even more so. The flow of food and aroma descriptors is trying to put into words a fleeting experience, and those who write them aren’t necessarily poets. But if you follow the work of a critic, even if you don’t get something resembling the same experience, you’ll start to pick up what he/she means.