History should not be a moving target, but sometimes it seems awfully hard to pin down.

I was already thinking about this before we visited the Delta Blues Museum in Clarksdale, Mississippi, yesterday. I’ve been sifting through a bunch of stories about Belgian White beers pre-Pierre Celis and many contain altogether different facts.

So two things from the Blues Museum. First, they’ve framed pages from a 1990 Living Blues article about Robert Johnson that includes maps to possible sites of the famed crossroads (where Johnson sold his soul to the devil in order to become a great musician) and to the various locations where he might be buried. The crossroads stuff is myth, of course, but the fact is nobody seems to be able to say for sure where his body ended up.

This doesn’t keep folks at each graveyard — in the early 1990s we used both sets of maps when we spent several weeks blues hunting in Mississippi, Arkansas and Tennessee — from claiming Robert Johnson is buried right there.

Second, the biggest display in the museum is set inside the sharecroppers cabin Muddy Waters lived in before leaving Clarksdale for Chicago. (Sierra isn’t into the blues, but she was pretty excited when she heard one of the songs. “Hey, Dad, that’s your ringtone.”)

The documentary showing on a screen behind a life-size wax statue of Waters (extra credit if you know his given name . . . without using Google or Wikipedia) includes an entertaining interview with Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones. He tells a particularly colorful story about when he first met Muddy, and the bluesman had white paint dripping off his head because he was up on a ladder painting when Richards walked in.

Problem is, Marshall Chess of Chess Records points out Richards’ story is ridiculous. You never would have found Waters in overalls, paint brush in hand. That’s in the documentary, but how many times has Richards told the story when Chess wasn’t there to offer a correction? Chess doesn’t doubt Richards’ sincerity. He says that could be the way Richards remembers what happened, just that he’s wrong.

I’ve experienced the same thing recently, talking to two different brewers about a conversation they once had. Each remembers the details differently. Is one right? Must the other be wrong?

Do we need an absolute answer? Do we discard both versions? Or make them both part of history and figure the “truth” will sort itself out? The thing is that Richards’ story tells you something about him, but in this case leaves a false impression of Waters.

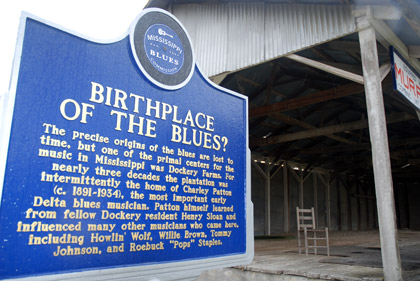

The photo at the top is from Dockery Farms, one of the stops on the Mississippi Blues Trail. Notice that despite the title on of the sign the following words acknowledge the blues didn’t have a single birthplace. That’s the way history works sometimes.

This sort of thing pops up in evidence in law once in a while. One of the reasons there are juries is the understanding that people see and recall things differently do to the combination of our imperfect capacity and that each of us have a different experience that informs the imperfect capacity. There is seldom a “right answer” but, as Ron Pattinson exemplifies, there are often better answers – which are sometimes not the accepted truth.

Mckinley Morganfield, I presume!

Keith Richards, like many other human beings, can be considered extremely unreliable as a witness…for obvious reasons…