Heikkie Riutta, a farmer in the Finnish municipality of Sysmä, won the Finland’s National Sahti Competition in 2006. He brews in the tradition taught to him by his father, one he will pass on to his sons. Sysmä is barley-centric, and like others in the region, Riutta brews his sahti without rye. Lighter color and lower alcohol strength are also typical for the region, and Riutta focuses on drinkability over alcohol strength, making beers in the 6-8% ABV range.

Heikkie Riutta, a farmer in the Finnish municipality of Sysmä, won the Finland’s National Sahti Competition in 2006. He brews in the tradition taught to him by his father, one he will pass on to his sons. Sysmä is barley-centric, and like others in the region, Riutta brews his sahti without rye. Lighter color and lower alcohol strength are also typical for the region, and Riutta focuses on drinkability over alcohol strength, making beers in the 6-8% ABV range.

In contrast, Veli-Matt Heinonen makes a stronger, sweeter sahti, like others found in the Padasjoki region where he lives. He learned to brew from his mother in the 1980s and the recipe, which contains about 10% dark rye malt, hasn’t changed much since. Before adding hops he puts them in a bucket and pours boiling water over them to reduce the bitterness.

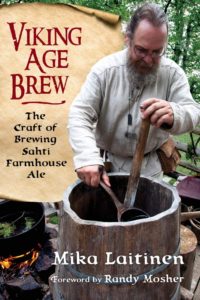

Mika Laitinen provides recipes from these two and others in Viking Age Brew: The Craft of Brewing Sahti Farmhouse Ale, the recipes supporting his assertion early on that sahti may be called a beer style but not by those who favor narrow style guidelines.

“Farmhouse ales always pose a challenge for those who want to categorize beers by style,” Laitinen writes. “Brewer-specific variation is enormous, and regional preferences may be overshadowed by ‘noisy’ individual examples.” In addition, these beers were not brewed to be shipped to a bottle share somewhere in the middle of the United States. Freshness is a gigantic variable. “The ale can taste different on the same day, depending on whether the pint was drawn from the top or the bottom of the fermenter.”

The farmhouse beers of northern Europe are not a final frontier — there is still plenty to explore beyond the western European and British influences that Americans have leaned on for more than 400 years — but they are old and new at the same time. Laitinen focuses on sahti, but his family tree of folk beers also includes Estonian koduõlo, Norwegian maltøl, Swedish gotlandsdricke and Lithuanian kaimiškas.

He suggests these are the best surviving examples of what European beer was like before professionally brewed hopped beer become commonplace in the late Middle Ages. They are not recreations of something from the ancient past, but survivors that reveal how people brewed beer with different raw materials and without using thermometers, stainless steel and many other modern amenities.

Laitinen collaborated on a Finnish-language book on sahti in 2015, but this is not simply a translation of that work. He ticks all the boxes you’d expect in a book devoted to history, ingredients and process. It should satisfy those who want to replicate, at least in a way that approximates, beers with a history as well as those who want to build on that history. His words reflect culture past and present, providing answers for those asking the question what is sahti?

And sustenance for those interested in what may still be ahead for beer.