So how come we don’t call beer geeks beerworms? Maybe because it sounds gross, but then why doesn’t bookworm?

Blame Stone Brewing in California – those otherwise sometime arrogant folks – for this question. Stone next month (June 4) initiates a Book & A Beer Club On the Grass at its modestly named World Bistro and Garden.

From the press release:

If this seems suspiciously similar to the type of activity enjoyed by little old ladies at the neighborhood Rec. Center, guess again. Instead of tea and biscuits—32 taps of beer and Arrogant Bastard Onion Rings! Imagine the possibilities…

I’m a sucker for the beer and book connection. It’s so civilized. After all, Brother Joris – the monk in charge of brewing the coveted Westvleteren beers – is also the librarian at the abbey Saint Sixtus where the beers are produced.

I’m a sucker for the beer and book connection. It’s so civilized. After all, Brother Joris – the monk in charge of brewing the coveted Westvleteren beers – is also the librarian at the abbey Saint Sixtus where the beers are produced.

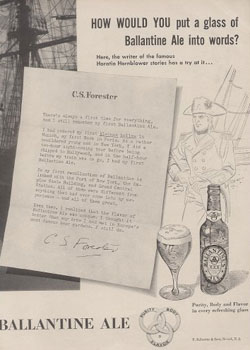

Back in the early 1950s, Ballantine Ale sought endorsements from many famous artists, including Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck. This one is from C.S. Forrester, with his answer to the question “How do you put a glass of Ballantine Ale into words?”

“There’s always a first time for everything. And I still remember my first Ballantine Ale.

“I had ordered my first helles in Munich, my first bock in Paris. As a rather bewildered young man in New York, I did a two-hour sight-seeing tour before being shipped to Hollywood, and in the half-hour before my train was to go, I had my first Ballantine Ale.

“So my first recollection of Ballantine is linked with the Port of New York, the Empire State Building, and Grand Central Station. All of them were different from anything that had ever come into my experience – and all of them great.

“Even then, I realized that the flavor of Ballantine Ale was unique. I thought it better than any brew I had met in Europe’s most famous beer gardens. I still do.”

Back to June 4 at Stone.

The first book up is The Omnivore’s Dilemma, the best book I read last year. Michael Pollan’s examination of industrial corn (the first section) seems to become more important daily (jeez, even affecting beer prices), but the second section (pastoral grass) is my favorite part of the book.

If you live close enough to Escondido to consider dropping by they’d appreciate an RSVP.

<

As I’ve written before, one of the categories here is Beer and Wine, not Beer versus Wine. When we have people over for dinner there will be men drinking wine and women drinking beer (and vice versa), and there might be a little conversation about one or the other but not why one is better than another.

As I’ve written before, one of the categories here is Beer and Wine, not Beer versus Wine. When we have people over for dinner there will be men drinking wine and women drinking beer (and vice versa), and there might be a little conversation about one or the other but not why one is better than another. So what about that? And who to ask? How about brewers? I printed out part of Russell’s column and took it to the recent Craft Brewers Conference in Austin. I showed it to a dozen brewers along with another old saying that farmers make wine and engineers make beer.

So what about that? And who to ask? How about brewers? I printed out part of Russell’s column and took it to the recent Craft Brewers Conference in Austin. I showed it to a dozen brewers along with another old saying that farmers make wine and engineers make beer.