Look closely at the label for TAPX “Mein Nelson Sauvin” from Private Weissbierbrauerei G. Schneider & Sohn. Those are hops. And the hops that make TAPX something different aren’t from Germany, but from New Zealand.

In this video Schneider produced to promote the new beer, available in limited quantities in the U.S. (my local store got six of the 750ml bottles), brewmaster Han-Peter Drexler says what’s been mentioned here before. That the Reinheitsgebot needn’t limit German brewers and that change happens slowly when it comes to beer in Germany. If you haven’t clicked on the video yet, go ahead, and at least hang around to get a look at the open fermentation vessels at Schneider. In Brewing With Wheat I try to describe what it’s like to stand in the midst of those tanks.

On his left yeast climbs high in a tank full of wort on its way to being the strong wheat doppelbock called Aventinus. On his right fermentation only recently started on what will be a batch of Schneider Original. A small hole opens in the middle of the yeast blanket, briefly revealing the wort below before closing again. It is alive.

Now you can see for yourself.

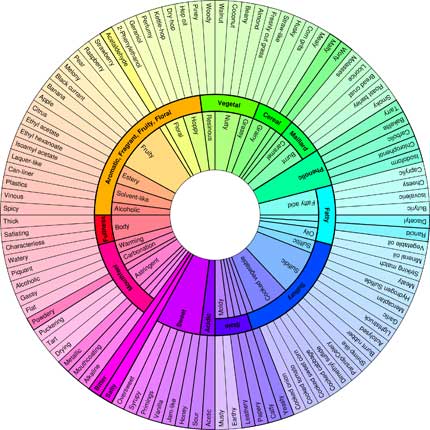

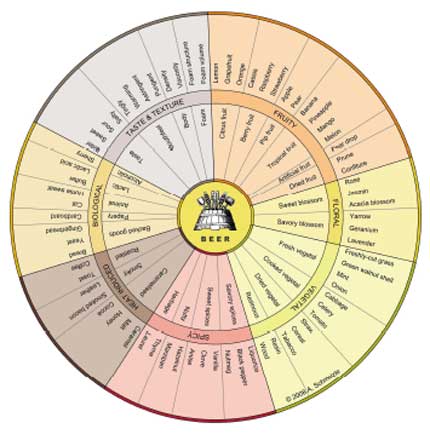

As the beer’s name suggests, the hop star is Nelson Sauvin, a cultivar noteworthy because of compounds1 that give it exotic fruit-like and white wine-like flavors; a grapefruit and rhubarb aroma akin to sauvignon blanc wine.

In the video, Drexler is already talking about next year, the next beer. His boss, Georg Schneider IV, is a sixth generation owner and properly respectful of tradition. He’s also committed to change. “The German beer market is deadly boring,” he told Sylvia Kopp in 2008, for a story that appeared in All About Beer magazine. “It is all very much the same. The tendency towards sameness is encouraged, for example, by our domestic beer tests rating beer only by its typicality and flawlessness. Creativity is only acted on in the beer mix category.”

This was about the time his brewery did the collaboration with Brooklyn Brewery called Schneider & Brooklyner Hopfen-Weisse. Most of that first batch was shipped to the United States, with only 200 cases reserved for Germany. When we were in Kelheim that fall there was no Hopfen-Weisse to be found. Now when you visit the brewery restaurant you can order the beer. Small change, but a change.

“If you brew a beer that not everybody likes, you have the wonderful effect that people talk about it,” Schneider said in 2008. And Drexler added, “We’ve got to take people by the hand and lead them to new worlds of taste. Customers, as well as chefs, culinary staff and traders, are searching for innovations.”

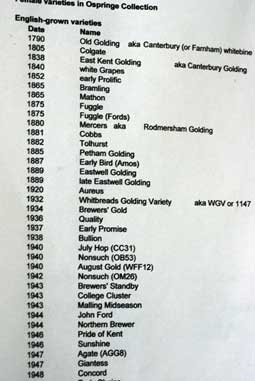

The video concludes with Drexler laughing as he explains that TAPX creates a platform for something new every year. He obviously enjoys the thought. Perhaps not in 2012, but surely soon, he won’t have to look beyond Germany for a hop with aromas and flavors previously considered exotic and unhop-like (or should it be un-hop-like or unhoppy? – whatever tells you this isn’t what brewers meant by “hoppy” just a few years ago).

Brewers attending the giant industry trade show Brau Beviale 2011 in Nuremberg earlier this month got a chance to rub and sniff several new hop varieties being developed at the Hop Research Center in Hüll. These cultivars are just ready for their first brewing trials and have many more tests to pass in the field before they end up in any commercially brewed beer. They don’t even have names beyond their designation within the breeding program; for instance 2007/018/013 tastes of tangerine and 2009/001/718 of watermelon, with grapefruit-like notes and also the impression of honey.

It’s going to be hard for the German beer market to remain “deadly boring” with hops like these.

1 3-sulfanyl-4-methylpentan-1-ol and 3-sulfanyl-4-methylpentyl acetate for those of you scoring at home.

The lead story in the latest issue of

The lead story in the latest issue of  Wye Hops is actually located on China Farm, one of several operated by

Wye Hops is actually located on China Farm, one of several operated by