A few years ago, Summit Brewing founder Mark Stutrud made a serious commitment to using locally grown barley (and a specific variety, Moravian 37) in Summit Pilsner. Listen to him talk in the video and you’ll think, yep, this is somebody who understands the importance of local.

So it is interesting to see him take a wait-and-see attitude toward using local hops.

“We’re keeping track of what’s going on in Minnesota, but a lot of folks who are starting hop farms in Minnesota don’t think of how they’re going to measure the quality of their harvest. Are they going to have a kiln? Will they pelletize or are they just going to grow the vines and say, ‘Come on over and pick them up?'”

The best the Hop Growers of America can figure Minnesota farmers planted about 20 acres of hops in 2014. But these are questions that need to be asked from the outset and often aren’t.

“I get these calls every day (from would be hop growers),” Sean McGree, hops manager at Brewers Supply Group, said the other day. “All they are worried about is getting their trellises in and hop going. They don’t realize that 60 percent of the quality that brewers see comes after the hops are picked.”

I’m more optimistic that farmers trying to revive hop growing in regions outside the American Northwest might succeed than I was three years ago, which is not to say I have any interest in investing in a hop farm. Picking and drying remains the next big challenge for many of them. But as Hop Head Farms in Michigan has shown it can be done.

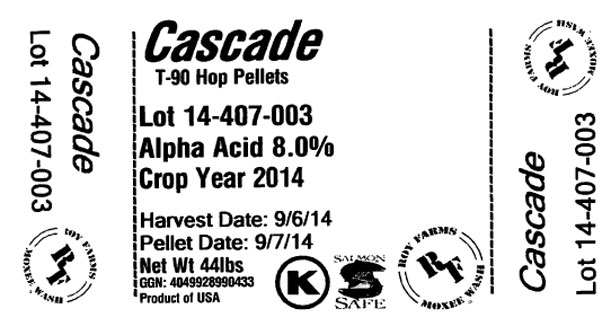

The image at the top gives you an idea of one of the standards they will be expected to meet. There’s a lot more to know about what’s inside the package than the percentage of alpha acids, which many new farmers can’t even provide. Roy Farms goes beyond most, for instance including the picking and pelletizing dates as well as the crop year, but the other number to look at is the lot. Roy tracks each lot literally from the time the plants are trained to string in the spring until they are picked, processed and packaged. Ever wonder what pesticides might have been used on the hops in the glass of “wet hop” beer you had the other day at your local brewpub? Perhaps you should. (You’ll also notice that Roy Farms is as Salmon-Safe certified grower.)

This isn’t exactly related, but in doing some research for another article I was re-reading part of “Hop Culture in the United States” (1883). In it there is a report of the Chamber of Commerce for Middle Franconia in 1879:

“American Hops (we have to admit this, though unwillingly) are greatly preferred in England to ours, and have decidedly taken precedence of us in that market. Taking the excellent qualities of our produce into consideration, such a result would be quite inexplicable, if it were not that the system of German commerce, unfortunately, has itself to blame, in part for this defeat. American Hops, no matter whether of better or inferior quality, almost always appear in foreign markets in their original state, whereas, with us, parties are not ashamed to make up for exportation, hops of all countries and all qualities, mixed together, often marked with best brands on the outside of the bales, but containing the poorest kind of goods.”

Next there is this account:

“A brewer in England, a short time ago, bought a bale of hops in Nuremberg, and thought he got the genuine Bavarian article. But when he opened the bale, a slip of paper with the name of a hop-growers in Eastern Prussia on it, was found. The hops had been sold in Allenstein, Eastern Prussia, and from there found their way to Nuremberg. Being of good quality, the Englishman sent the grower, in Prussian, an order for more hops. A still more striking instance of such dealings happened in Wurtemberg, Prussia. A brewer, of that place, was prejudiced against the hops of his own country. He refused to buy hops in the Allenstein market. He wanted the genuine article from Southern Germany. He bought all he needed at Furth. But what did he find one day in a bale of Bavarian hops? A business card with the name of his next neighbor, a hop grower, whose hops he had declined to buy at any price. Unwittingly, he had taken them many a time at a fair premium, when they were sent by some Bavarian hop dealer.”

Kind of funny, but not really.

When they get to marketing their hops, the Minnesota growers should mention that they are “the genuine article.” A shame that phrase has fallen out of favor.