Alan McLeod asked a question a while back that, to be honest, points to a liberty I probably should not have taken in For the Love of Hops.

A question about “landrace” however. I understand it represents as a word the division between husbandry and wild. A word of the 1700s perhaps. When you looked at Cluster and described it as a landrace, would you only use the word if the hybridization occurred in the wild as Dutch plantings met their New York forest cousins? Or does it include the potential for intentional 1600 Dutch hop breeding in the Hudson?

His question resulted from a) others he has related to Albany Ale and the Dutch settlement of the Hudson Valley, and b) a headline I wrote on a sidebar in FTLOH: “Cluster: America’s Landrace Variety?” Bad headline, because who notices the question mark? It was a mistake to go beyond what I wrote in the body: “in a sense selection was much like the landrace varieties on the Continent and in England.”

A mistake because there’s enough lack of clarity looking backward, trying to sort out the origins of hop varieties, that mucking with the definition of landrace only makes it worse. Obviously, there’s more detail in the book, but here are the basics in short order:

Breeding and landrace hops

From the time hops were first cultivated more than a thousand years ago farmers chose to grow varieties, first found growing in the wild, based on their brewing and agronomic qualities. They were simply clonal selections, but different varieties emerged as plants naturally cross-pollinated. The best endured and are called landrace varieties by hop geneticists. The short list includes Saazer types, Hallertau Mittelfrüh, Fuggle and Golding. An argument could be made for others like Hersbrucker and Strisselspalt, but that is tangential.

What’s important for clarity is that these are all hops of European origin. The plant has been around at least six million years, likely originating in Mongolia. European types diverged from the Chinese varieties more than a million years ago, American types more like a half million years ago. American varieties contain compounds that may create odors that result in aromas and flavors once considered undesirable but now highly sought after.

Modern hop breeding, that is hybridization, did not begin being until the twentieth century. Research by the Austrian monk Gregor Mendel in the mid-nineteenth century (which went unrecognized until about 1900) established that, contrary to Charles Darwin’s theories, certain traits may occur in offspring without any blending of parental characteristics. His principles laid the foundation for plant breeding programs that created entirely new varieties, including hops.

Perhaps it would have happened anyway, but we can point to a time when hop breeding changed and therefore hops themselves. Not long after E.S. Salmon took charge of the program at Wye College in England in 1906 he set out to combine the high resin content of American hops, including some found growing wild, with the aroma of European hops. This eventually resulted in hops with more than 20 percent alpha acids, compared to four percent common at the beginning of the century, and a much wider range of aromas.

Clearly the Dutch and others growing hops in America in the 1600s were not breeding in the modern sense. But they were doing just what farmers were in England and on the Continent — always trying to identify the best plants and further propagate them. These likely were a mixture of imported European varieties and wild American types. None persevered, however, unless as part of the Cluster variety.

Cluster hops

Here’s what Steiner’s Guide to American Hops had to say about Late Cluster in 1973:

“The Late Cluster is the oldest American variety grown continuously in the Northwest. Known as the Pacific Coast Cluster, it was widely grown at the turn of the century and was the leading cultivar, until the decline of acreage in California and Oregon was counter-balanced with the growth of the hop industry in Washington, where the Early Cluster became dominant. The origin of the Late is obscure, but it was probably originally derived from the native North American hop.1 It may have been a selection from these, or resulted from a cross with introduced varieties brought over by colonists, or from a cross of native western varieties with stock brought by settlers who established hop growing in the Pacific Northwest. The Late Cluster was similar to but more vigorous than the Milltown, and other strains of Cluster grown in New York State, after the Prohibition Era.”

One other important note from Steiner: “Any cultivar grown widely and continuously over a long interval of time, will, if not occasionally reselected, accumulate a large number of mutations. … Thus the Late Cluster is actually a collection of similar clones rather than a distinct homogeneous cultivar.” Early Cluster, given that name because it matures earlier, likely was a mutation of Late Cluster, and more widely grown. Together the accounted for almost 80 percent of American hop acreage forty years ago.

I suggested calling it an “American landrace” variety because it resulted from clonal selections and remains around today (amounting to less than 2 percent of the American crop). In that way it is much like Fuggle, itself shrouded in some mystery, or Saaz. However, genetically, it is much different. And that’s a difference to pay attention to.

*****

1 Genetic studies since proved that Cluster is a cross between European and American varieties.

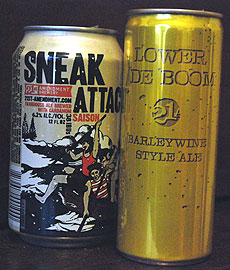

See that sleek, gold can on the right that looks like it’s waiting to make an appearance in Super Bowl commercial? Brilliant idea. It contained1 8.4 ounces (248ml) of Lower De Boom barleywine from 21st Amendment Brewery.

See that sleek, gold can on the right that looks like it’s waiting to make an appearance in Super Bowl commercial? Brilliant idea. It contained1 8.4 ounces (248ml) of Lower De Boom barleywine from 21st Amendment Brewery.  Mark Dredge has an excellent post on a couple of English hop varieties that were once rejected — so officially, I guess, they never became varieties — that now

Mark Dredge has an excellent post on a couple of English hop varieties that were once rejected — so officially, I guess, they never became varieties — that now  Adam at

Adam at